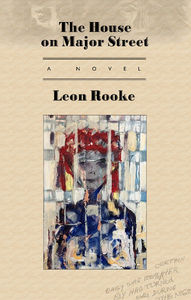

Read an Excerpt of Leon Rooke's The House on Major Street

Leon Rooke has been an important part of the Toronto literary scene for decades, so it is perfectly fitting that his newest novel, The House on Major Street (Porcupine's Quill) has an unapologetically Toronto setting (and title, referencing a residential street in the Annex neighbourhood).

The story follows Zan, a teenage girl who hops on her bike to buy some cat litter and sets off a chain of events that will rock her tight-knit street of strange and lovable personalities. Her cycling accident lands neighbour Tallis in a coma, and strange events spin out from there, with meta-appearances from literary characters including Ryabovitch from Chekhov’s short story "The Kiss". As characters come together and spin apart, one question remains, driving the tension forward: What will happen when - if - Tallis wakes up?

We're very excited today to bring you an exclusive excerpt from The House on Major Street, courtesy of Porcupine's Quill.

An Excerpt from The House on Major Street by Leon Rooke:

Early in the morning a lady with a lapdog showed up at the house on Major Street. She said she was looking for a former cavalry officer, Ryabovitch by name, whom she understood had struck up a friendship with a young boy presumably residing at this address. Ryabovitch was in fact upstairs at the time, contemplating flight through a window. He had heard the yapping dog. He could leap to the porch roof, possibly without breaking a leg, and make his escape. Romance had not come easily to him. It surprised him that it had come at all. That Anna Sergeyevna was a glorious woman he had no doubt. But intense, my word!

Emmitt Haley, father of the young boy, answered the woman’s anxious summons. He wore only pajama bottoms, his feet bare, the day brutally cold, boasting a sombre blue cast. Rainfall, intermittent. It took him some time to understand what the harried woman was saying. Her accent was unfamiliar, her manner troubling. Sorry. What? Who?

Ryabovitch. I know the snake resides here.

A snake?

Da, and a snivelling rat.

Finally, Emmitt comprehended that this snake, Ryabovitch, Ryabovitch the pig, had trampled on this woman’s heart. How distressing. But it was difficult to concentrate on her words. An icy wind was blowing. His feet were numb, fingers getting there.

But, but, but. Now rain was falling harder. Icy pellets striking his toes. The visitor appeared not to notice the rain. He was trying to tell this berserk woman that no one bearing the name Ryabovitch lived in this house. Friend of my son? This minute upstairs in bed, comatose, and conceivably never to emerge! Not possible. Lady, you have the wrong house. But his tongue was tied. He ached with cold. He ached to say to the woman, Lady, I am not up to this ordeal: a bad, sleepless night after so many. You come at a bad time.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

At that moment the woman let out a shriek. She had seen, inside the house, a speeding blur. Descending the stairs. A speeding blur.

There he is!

Such was her shriek. Shrieks. An instant later, she was scrambling to get past him. To get through the door.

Lady!

A variety of shouts, random noises—pandemonium—brought Emmitt’s wife, Daisy, to the door. She had been in the kitchen dully watching eggs boil in a pan of water. It could be admitted that she had been watching this boiling water for some duration. Sooner or later those eggs will find their way into the garbage. She was partner to a pill-induced slumber, let’s say. Xanax, perhaps. Lorazepam. What else? She has her secret stash. She has her reasons—her beautiful son may never again waken to the real world.

So here she is, on this cold wet morning, shoving her husband aside. Actually punching him—hair not yet combed, dingy gown about to fall off her—a slattern! What has this once-attractive woman done to herself? A professor of English literature, for God’s sake! On medical leave, just now. Appalling developments here at 2X8 Major. She, too, is yelling: ‘My God, Em, why are you making that woman cry? Have you lost your senses? My God, Em, let the woman come in!’

For some minutes, the dog had been yelping. She was a nervous dog, strongly opinionated. Pomeranian by appearance. Not that Emmitt or Daisy knew a Pomeranian from a sheep dog or any other. The Pomeranian dog could have told everyone the scoundrel Ryabovitch had been in there. She hadn’t seen the blur, but had smelled him. Now he was gone. The whole business had been a waste of time. Her mistress always fell for rotters. Consider that rotter husband back in Russia, for instance. A flunky, a lackey. Consider that dolt Gurov she succumbed to in Yalta. Such has been her whole life’s story. The Pomeranian loved her mistress, but God knows Anna Sergeyevna did not make this loving easy. No more than did that other dolt, Chekhov, when he set out to write the true-life story of a good dog . And got everything wrong. Sitting in Varney’s pavilion, Gurov saw, walking on the sea-front, a fair-haired lady of medium height, wearing a beret, a white Pomeranian dog running behind her. A lie. The few times she’d allowed herself to run behind Anna it was solely so she could nip at her heels. Hurry her along. The time the lazy author was writing about she’d been splashing through blue waves, chasing a seagull. Never trust an author was the Pomeranian’s motto. In fact, in her estimation a wise Pomeranian—herself—while the most sociable creature on earth, trusted no one.

What might an erudite scholarly wag say of this hodgepodge lacerating 2X8 Major?

Help, help!

Ours is a house occupied by the blind, the deaf, the mute, the totally helpless! We are lame, we are crippled, we are maimed and tormented, socially inept, bunglers of the first rank, mental midgets bereft of hope! We crawl about on hands and knees, we cry out (help, help!). We crouch in dark corners, entreating our captors: What have we done? Why are you doing this to us? Mercy! Mercy!

Hurry, friends, with news of our desperate plight. Inform the police, the military, the press, the very topmost, exalted despots of our great country. Barons of the left, moguls of the right, pillars of the very centre-most centre. Our dye is cast, our pigment set.

Oh, help us.

Forget latitude, longitude, write down this address: two-x-eight (2X8) Major, a stone’s throw from Bloor Street’s best. Heart of the heart’s heart. A scholar’s digs. Known land of the Mississauga Anishinaabeg, Haudenosaunee and Wendat peoples. Turn where you see the Bloor SuperSave. You have passed Trinity Church. Go back. One two three, how many doors south. Red brick house (renovated not, and no plans to). Lacy windows, how many bodies buried in the basement, beaten shrubs by the front walk, rubbish today swirling, snow a mile high. Rain, intermittent.

You can’t miss it. Extreme measures are called for, don’t even think negotiation. Too late, too late! Beseech our liberators to arrive with tanks, flame throwers, scud missiles, pots and pots of chicken soup; have phantom jets strafe our house and thousands of enraged crusaders lay siege to our door. Be warned, bad news awaits ...

Be cool.

Hang easy.

Save us. We perish by the hour.

Click here for more information on The House on Major Street by Leon Rooke.

_________________________________________

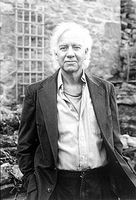

Leon Rooke is an energetic and prolific storyteller whose writing is characterized by inventive language, experimental form and an extreme range of characters with distinctive voices. He has written a number of plays for radio and stage and produced numerous collections of short stories. It is his novels, however, that have received the most critical acclaim. Fat Woman (1980) was shortlisted for the Governor General’s Award and won the Paperback Novel of the Year Award. Shakespeare’s Dog won the Governor General’s Award in 1983 and toured as a play as far afield as Barcelona and Edinburgh. A Good Baby was made into a feature film. Rooke founded the Eden Mills Writers’ Festival in 1989. In 2007, Rooke was made a member of the Order of Canada. Other awards include the Canada/Australia prize, the W. O. Mitchell Award, the North Carolina Award for Literature and two ReLits (for short fiction and poetry). In 2012, he was the winner of the Gloria Vanderbilt Carter V. Cooper Fiction Award. He lives in Toronto.