I Promise You, It's Fiction.

By Zalika Reid-Benta

Full disclosure, I had another post planned to kick off my Writer in Residency here on Open Book but I decided to change topics after seeing a write-up/review of my forthcoming short story collection. So far I have been very lucky to receive positive commentary on Frying Plantain, of course in a few articles, words and sentiments like “semi-autobiographical”, “reads like a memoir”, “feels more like a memoir” have cropped up. The characterizations aren’t new to me. One of the reasons I decided to do an MFA in the States was because in every Toronto creative writing class I’d participated in, a majority of the other writers assumed my stories were based on my life. In fact, during one of my workshops, after a couple of people asked why I wouldn’t change my character’s name from Kara to Zalika (“because I’m writing fiction”), another writer spoke up about her story, which was about an assassin who could turn into a cat and said, “Wow, I hope no one here thinks I can transform into an animal just because I’m Japanese-Canadian like my character.”

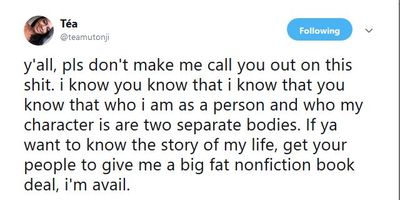

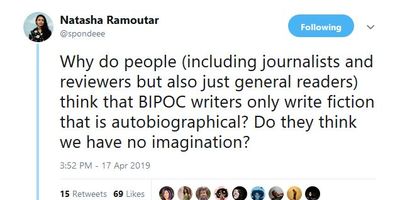

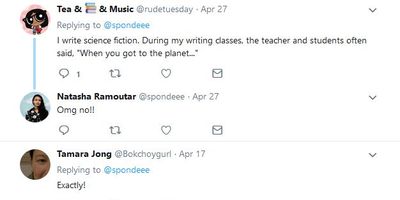

It is certainly true that as an author you can’t control readers’ interpretations of your work (where’s the fun in that?) but as my collection begins to make its debut, I’ve begun thinking about the particular interpretation (and sometimes assertion) that my book is autobiographical: is it because it’s in first person? Is it because it follows one protagonist throughout twelve stories? Is it because of a particular preconception? The assumption that BIPOC writers are, for some reason, masquerading memoir as fiction has been a notion recently challenged on Twitter:

To dig into this sentiment, I wonder if readers automatically assume (subconsciously or not) that imagination inherently belongs to white characters and that fiction, whether it’s fantasy or realism, is somehow owned by white writers. Perhaps they believe we lack the imagination to create scenarios for our make-belief characters and in relation, perhaps they lack the imagination to view BIPOC characters as anything other than avatars for real people.

My thought process then led me to wonder what constitutes “autobiographical” in the minds of readers. Throughout Frying Plantain, Kara lives in different parts of the city — neighbourhoods that I’ve also lived in but does the fact that I once lived in the Vaughan and Oakwood area and the fact that I have also shopped at Eaton Centre mean that I am Kara and Kara is me?

I, like many Black, Indigenous and people of colour, had to navigate casually as well as aggressively racist remarks from other students in high school; a reality that Kara has to work through in a couple of my later stories. Does giving your protagonist experiences that you can relate to in situations that have never happened to you automatically constitute your book as autobiographical? Or is literature more nuanced than that? I happen to think it is. This collection came out of me wanting to write a book I would’ve liked to have read growing up, it came out of an instinctive desire to see Jamaican-Canadian girls represented, to see the food I eat, the slang I hear, the tensions I’m interested in on the page. It came out of me wanting to write about an experience I, and people like me, could relate to, but writing about experiences I can relate to doesn’t mean the life in the stories is literally mine.

Speaking to one of my friends, I’d unloaded my fatigue at the characterization of my collection as autobiographical, referring to one of my stories (“Snow Day”) saying, “Sure, I went to New Orleans Donuts when it was still around but I wasn’t harassed in a bathroom like Kara was, that wasn’t my life.”

She responded with, “No, but getting harassed in bathrooms as a teen? That was mine.”

Of course, not every writer views the assumption that their work is autobiographical as a necessarily negative thing. A few years ago when I brought my concerns up to a mentor of mine, they just waved it away.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

“It means you’ve written something so realistic people can’t even believe that it’s fiction. It’s the highest compliment!”

The views expressed in the Writer-in-Residence blogs are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Zalika Reid-Benta is a Toronto-based writer whose work has appeared on CBC Books, in TOK: Writing the New Toronto, and in Apogee Journal. In 2011, George Elliott Clarke recommended her as a “Writer to Watch.” She received an M.F.A. in fiction from Columbia University in 2014 and is an alumnus of the 2017 Banff Writing Studio. She completed a double major in English Literature and Cinema and a minor in Caribbean Studies at University of Toronto’s Victoria College. She also studied Creative Writing at U of T’s School of Continuing Studies. She is currently working on a young-adult fantasy novel drawing inspiration from Jamaican folklore and Akan spirituality.