“A poem discloses something,” an Interview with AF Moritz

By James Lindsay

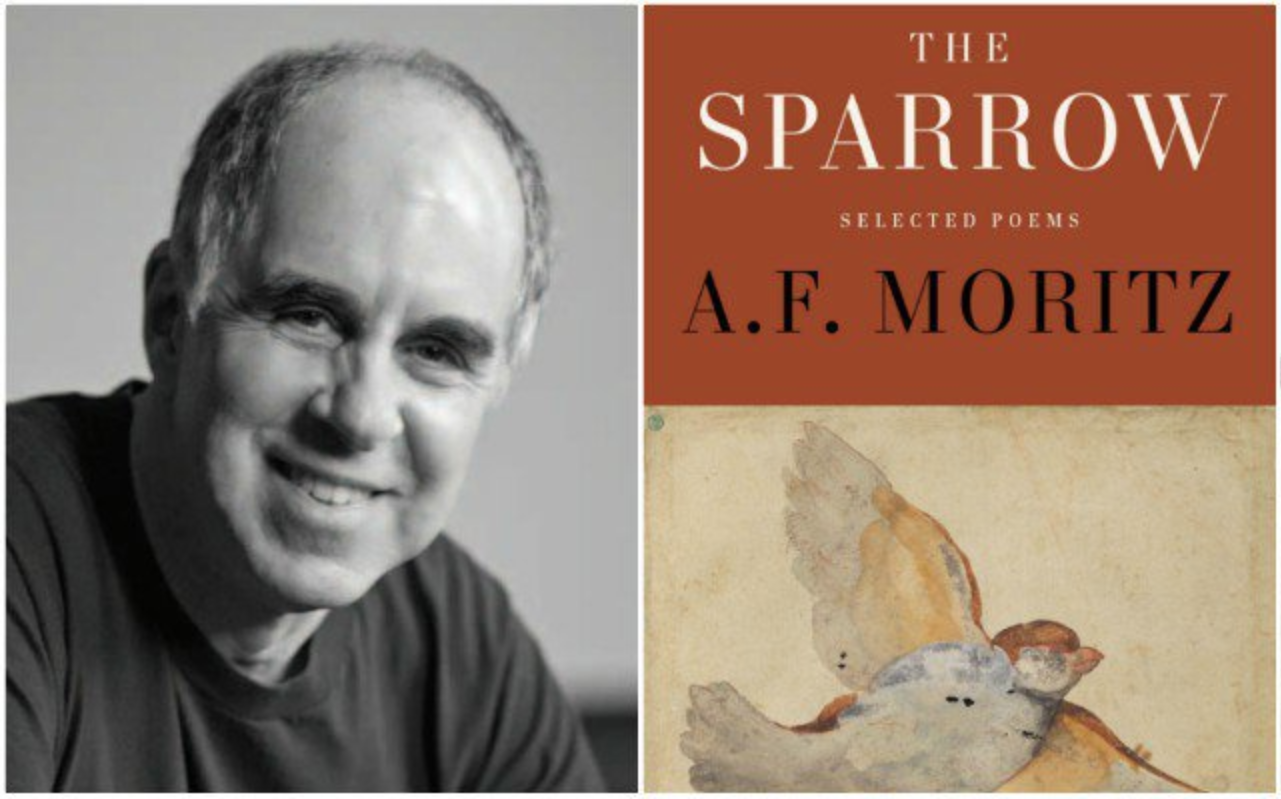

If there is such a thing as an eternal place, poetry of AF Moritz inhabits it. In his work, history, myth and nature provide scaffolding that holds epic-minded verse, at once in awe of beauty and trembling before the ugliness of violence and its consequences. When reading The Sparrow, Moritz’s latest selected poems, I was taken aback by how fluid it all seemed—it felt like reading a single, very long, very old sequence that is determined to smoke-out something from a thick, thorny brush, knowing that it’s target unknowable, yet still set in its ways.

James Lindsay:

The Sparrow collects over forty years of your poetry. What was it like to look back at your life's work and how did it feel to consider poems you may not have even thought about for many years?

AF Moritz:

I love having The Sparrow now but for a long time I resisted requests to do a selected poems. Once I settled down to accepting it, though, I found it a very rich experience. Both my resistance and the exact moment at which it crumbled feel right to me. Earlier, some of what needed to be in it would not have been written yet. Now, it’s a sort of gathering point on a trek, where the whole caravan can halt, be counted, rest, get ready to move on.

The main things that impressed me were that I liked the poems and didn’t want to change them, that they did indeed develop each other and talk to each other across time, and that because of this I could learn from them what I’ve been as a poet. This has let me get a clearer view, I think, of what I should become. Another thing I liked was a discovery that made selecting the poems for the volume both easy and hard: I thought that virtually all the poems could have gone in. So it was very difficult to decide what to leave out. But on the other hand, this confirmed to me that there are many ways of looking at my work, and many facets that could be brought out by different selections from it.

What the book teaches me is still to come for my work falls into several categories, somewhat contradictory ones. I’ll mention two, just because they’re clearly contradictory! First: There are a lot of specific things of the world that have not yet appeared, things that I love, am concerned for, am troubled by. A subset of this is that, while I like the poetry I’ve devoted to favorite themes, let’s say childhood or desire or justice, I don’t think I’ve done enough with these. In other words, so far I’ve neither been comprehensive nor deep enough on the things that are dear and crucial to me. I recognize, though, that this “discovery” is one I’m always making, because the things are inexhaustible, and I will never mention every aspect of them or get to the very bottom of them. Thank God.

Second: Even though I’d like there to be many more things in my poems—for instance, I have the idea of writing a book that would be a kind of dictionary, with each poem being a “definition” of one thing that is basic to me: creek, milkweed, ladybug, goldfinch, smell of tar, steel mill, beggar, and so forth—the fact is that my poems are stuffed with things and I’d like at least some of the ones to come to be much more essentialized. I’d like to add to my work an entire additional work of small, spare, even “abstract” poems that are directly about eternity with no concession whatever to the taste for descriptive language. What do I mean? Well, as an example, here’s a poem by Jiménez:

I know you the eternal newborn

who takes in the scarlet sun that dies each instant

in the sunsets of my life.

If you need to know exactly how, and in what events, each instant of a life is a sunset that is simultaneously a newborn who takes in the setting sun, takes in the beautiful fire of it, as a plant takes in the soil and as a good person takes in a poor old man and of course as a child takes in the whole world into which he’s born and which is passing away...if you need this spelled out in any way, Jiménez isn’t going to say one further word to satisfy your need for entertainment. Entertainment can be left aside; beauty is enough. The three-line poem has already said it all, absolutely all, and so, “He who has ears to hear, let him hear.” I want to write just like that, and there’s not nearly as much of that as I want in my poetry so far.

Well, this is a long answer! So just let me quickly answer the other part of the question. There weren’t really any poems I hadn’t thought of for a long time. I have a process of constantly referring to my own work to help with my current poems. And I did go through an experience like this once before, thanks to Paul Vermeersch. Paul asked me in 2000 to republish my first four books, and that volume, Early Poems, was very important to me, and involved a comprehensive look at my earliest published poems, including some revision, not much, but a lot more than I did for The Sparrow. In fact, the existence of Early Poems helped with The Sparrow because, since it’s still in print, it allowed Michael Redhill, Kevin Connolly and I to decide to severely restrict the representation of those books and give more space to some of the middle and later ones.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

JL:

One of the things I was stuck by while reading The Sparrow was how cohesive the poems felt. For comparison, I had also recently finished reading Frank Bidart's collected poems, Half-Light, and noticed how many different kinds of poems he has in him, how drastically his poetry has changed over the years. Your work seems more determined to me, as if it were tenaciously exploring a single, unknowable thing. The "eternal newborn who takes in the scarlet sun that dies each instant."

AFM:

“Tenaciously exploring a single, unknowable thing” is an excellent way to say it, I think. I especially like how you say it’s the work that’s determined to make this exploration, not me. Of course, I am involved. It’s really “unknowable” how much I plan out a progress and how much a path simply opens.

That experience, actually, is one aspect of the unknowable that’s there to explore: the paradoxical, seemingly impossible reality, which the poet knows as a concrete experience, that a poem is given and manufactured. It comes from who knows where, could never be “invented” by any conscious determination to get oneself a poem, and at the same time, it’s laborious, consciously created, polished and changed, could always be criticized and opened up again and changed again, and simply would not exist without the poet’s planning and reasoned effort.

You realize, as a poet, that the argument, whether there’s inspiration and intuition and a connection to and communication from “the beyond”, or whether on the other hand there’s only intentional planning and construction, is in fact silly, although the very nature of reason limited to rationality, logic, and planning automatically creates this false dilemma and can’t avoid doing so.

It’s a sort of dialogue, a back and forth. A poem discloses something. You think, consciously, about exploring that thing, writing another poem to do it. When that next poem gets written, though, there’s a lot in it that was not your conscious intention, although there’s also a lot that was. And in fact, often your intention to write the second, answering poem fails. It is too entirely a matter of planning, which cuts off the openness that starts the flow of any true poem. Too much intention blocks openness, surprise. Maybe you try, but what emerges is mechanical, too merely a matter of intention. So it goes in the wastebasket. And then, months or years later, you realize that an entirely different poem, which came from a different impulse, a seemingly unrelated poem, in fact is that poem you hoped to write so long ago, to answer or complete a part of your work.

JL:

But I wonder, what is the difference, the progression you see between your early and later work?

AFM:

I could answer it in terms of various concerns, but they all constellate. The one I’ve just mentioned is a good representative for all of them. I’m always exploring the convergence, in a self or a society, of its openness to springs of life with its own self-conscious ideas and its purposeful activities.

Obviously, this has a lot of dimensions. Right from, “What are ‘springs’ and ‘life’, are we talking about ‘the origin’ or ‘God’ here?” to the great “Manichean” question, “Springs of life, fine, but aren’t there springs of evil and death too, and are you telling us that evil and death emerge only from what you call ‘a self or a society’s own self-conscious ideas and its purposeful activities’?” That is, does our life contain a co-presence and conflict of evil and good, or can we say that evil is subordinate to good, less real, less “original”? If only humanity really creates evil, does that somehow make it less ultimate? You’ll notice this turned over again and again in my poems.

I’d say that the “progression” of my poems is simply the dialogue I mentioned above in which each stage achieved, each poem, enlarges the view and sharpens the passionate feeling of this crux of life.

That’s one reason why I decided to take out two poems and use them as a “prologue” and a “coda” to The Sparrow. The prologue poem, “We Decided This Was All”, was written in 1981, and the coda poem, “The Last Things” in 1976. In other words, I took both introduction and the conclusion from my earlier work, and I placed the earlier poem at the end.

On top of whatever else this may mean, it expresses my sense, which I’d like to make clear, that I’m doing just what you said, pursuing a continuous exploration. It means that I don’t abandon earlier intuitions that I find were on the right track. Expression and development change, even vision changes, but it’s change in the same vision that was glimpsed, and pursued for a clearer glimpse.

But I should give at least a bit of concrete example. “We Decided This Was All” has the speaker waking up into the world of evil characterized by the Holocaust, and the culture of futile and self-exculpating response and non-response to this evil. He’s waking up from a childhood dream of a good world, a dream of a sort of social Eden. So there’s the contrast of the experience of an “original innocence”, and against it, a civilized evil of constant human wrong-doing and fatuous analyses. These analyses--the flood of words, "discourse", the opposite and parody of poetry--never end and become a sort of entertainment and distraction and feed a self-conception that people like to have of themselves as mentally tortured in the midst of their comforts. And little do they know that profoundly this is even true, in a way they can rarely recognizes, but which subconsciously determines their will to suicide, whether in terms of direct suicide, or scorn and violence against others, or a lapse into triviality and boredom, the suicidal form most common in North America.

Coming to adult consciousness and realizing he was born into this situation, the speaker doubts himself, his original innocence, his glorious and generous vision. I might say that the ultimate meaning of the poem, at least in so far as I can grasp it now, is that the person realizes that he is both the child self and also the creature of this “civilization” and he is agonized by this fusion which is at the same time a rupture, this body which is at the same time a wound.

You can easily see, then, this same theme repeated in a poem placed later in The Sparrow, “The Sphinx”, but drawn from the same original volume, The Tradition (1986; 2nd ed. 2015).

Then, coming to the conclusion or coda poem, “The Last Thing”, you can see that it's like a hymn of joy to the original innocence aspect of “We Decided This Was All”. I meant the poem's placement to be an affirmation that the original goodness of life is indeed what is original, and that it is permanent. I meant that this is not a wish, or a philosophical idea of optimism, but a profound feeling from a direct experience of the core of existence and being. This is a direct seeing that later is put in “intellectual” terms because as talking beings we have to do so to express ourselves. But it can only be put in proper intellectual terms by poetry, precisely because poetry's intellectual terms are not wholly intellectual, but of the whole person, and so are not, in a sense, "intellectual" at all but rather "poetic", which includes and subsumes all intellectuality. The poem is not simply intellectual but a complete mixture of the intellectual, sensuous, and passionate. It relentlessly turns the arrow of the mind away from the mind and back to body and earth and the touch of the loved one.

The last thing I’d say about “The Last Thing” is that, as placed in The Sparrow, it comes right up against poems that are fragments from near the end of my most recent book, Sequence (2015), and these poems have exactly the same theme of the perpetual presence of childhood, the new beginning, the possibility in all circumstances of a new beginning.

In dark times, poetry has to be under the sign of hope. And with hope, thinking is really from the end, not the beginning. It's realizing that the always possible beginning is the permanent, if hidden, presence of the good end in every moment. "Origin" really means not so much any past but the fact that, in a time of evil and hope, the structure of existence is this: a beginning toward the good that is always possible and always needing to be made possible again.

I think that this is not abstruse philosophy but the most concrete of the most concrete realities. I think that if people would look at themselves clearly, they would realize that this is exactly what they live, at least whenever they are not busy giving up or going along. This is what they are when they're at their best, when life is truly life.

JL:

In his novel Leaving the Atocha Station, Ben Lerner writes that John Ashbery’s, “flowing sentences always felt as if they were making sense, but when you looked up from the page, it was impossible to say what sense had been made . . . there was no actual organizing logic or progression.” I couldn’t help but think of this quote when reading your last response. Your poetry seems to share this immediacy, this in-the-moment logic, this permanent origin. Yet narrative often frequents your work in a kind of Beckett-esque way: a character finds themselves somewhere and begins to explore, but when we look up from the page, no progress has been made. Could you comment on the narrative aspects of your work?

AFM:

Thanks for the quotation from Lerner, and your commentary on it. I think this applies to my work very exactly.

First of all, I could go back to what I said about “origin”. It’s a myth, in the good sense, because it inevitably suggests a deep past and a story of a movement from that past. But what it actually expresses is the structure of every moment, whether you consider a “moment” as an instant of an encounter with a person or thing, or as a brief unified experience like waking up, or as a unified social experience, like a hopeful social movement or revolution. I always keep before me Gerard Hopkins’s famous lines. He states that human cussedness has “bleared, smeared” everything, has walled us off from nature and has made everything “wear man’s smudge” and has made the earth “bare”, and then immediately he turns around and says that, despite all this, “nature is never spent; / There lives the dearest freshness deep down things”. In other words, the origin is always, and the story of our movement from it, for good and ill, is a story that happens every instant, though it also happens over time.

I could say that Hopkins’s phrase is one of my poetic mottoes: “There lives the dearest freshness deep down things.” I have various ones. Tennyson: “The mighty hopes that make us men.” Wallace Stevens: “Profound poetry of the poor and of the dead”. Jiménez: “Poetry and love every day.” A few others.

JL:

Do you use or dialogue directly with Ashbery’s poetry?

AFM:

Very much so. Ashbery’s work impressed me profoundly when I was 19. And I’m still stimulated by it and frequently get a return of the old astonishment. One’s tempted to think that Ashbery became too much like himself in his later books. I myself have sometimes said this. But I’ve just been reading Quick Question and Commotion of Birds, and these are profound, surprising, beautiful.

How sad that everything has to change

yet what a relief, too! Otherwise we’d only have

looking forward to look forward to.

The moment would be a bud

that never filled, only persevered

in a static trance, before it came to be no more.

That’s from “Words to That Effect” in Quick Question. That’s classic poetry with the necessary transformation into our terms. It has the ring of today. Yet it’s exactly, for instance, William Blake!

Time is the mercy of Eternity; without Times swiftness

Which is the swiftest of all things: all were eternal torment...

I discovered Ashbery just in the course of going through the university library and reading every volume of poetry, new or ancient, I could find, rather than paying any attention to my studies. At that time there were just his first three books, Some Trees, Rivers and Mountains, and The Tennis Court Oath. How I loved those books! Pretty soon The Double Dream of Spring came out and that was an amazement. And Three Poems. In all these books there were examples of new ways of handling narrative, a new way of dissolving narrative, if I can use that term, in meditative lyric, or in pure lyric.

I was already pursuing such new ways on my own and through the example of classic surrealism, because I’d quickly gone from the American quasi-surrealism of the time—Mark Strand, Robert Bly, James Wright, Charles Simic—to Surrealism itself and André Breton. Breton’s poems incorporate and “dissolve” or disperse narrative in a way that parallels and yet is quite different from the ways found in Eliot, Pound, Joyce, W. C. Williams, Hilda Doolittle. The incorporation of narrative as structure and source of meaning, usually ironic, and in a way that is both backgrounded and basic, was central to the modern tradition of the “condensed epic”, like The Waste Land. Having a dissolved narrative, largely present through allusion and implication, left the overall poem free to be lyric, meditative, dialogic, conversational, scholarly and documentary, polemical, etc., while still having a firm, if mobile, structure.

Ashbery was yet another form of this movement of the transformation of narrative: another way of incorporating narrative. I decided that in the late 1960s when I was in university, it was the absolutely contemporary form in which narrative could be made living, the one emerging “now”.

Your words, and Lerner’s from his novel, define very nicely one of the things that impressed me most. Here was a new way, our way, of living the mystery of timelessness in time, time in timelessness: that paradox, that seeming contradiction which is life itself when life doesn’t give up on itself.

JL:

Would you say that this idea you had caused your earlier poems to resemble Ashbery’s in form or style?

AFM:

Some poems do have echoes and resemblances, especially ones in Here (1974), but I never wrote like Ashbery. At one time I wouldn’t have said this, but looking back, I can see how strongly the early poems that have a redolence of Ashbery have much stronger echoes of classic surrealism, the great mid-century European poets (especially, in those days, Seferis and Montale), Baudelaire and Rimbaud and the French symbolists, and my Ur-influence, the English Romantics, among whom I include the Victorians.

But the presence of Ashbery is indeed essential and incomparable in its own way, even though the procedure of my poems is very unlike his. The difference is that my poems do have temporal, logical, and structural definition, including to their narrative elements to a degree. And thus they do have progress, of story or argument, as the case may be, or both.

I want there to be progress! The circularity and the constant co-presence of the same things is there, yes, but so is time, history, effort. I want there to be human progress. For me, the sense of timelessness and repetition does occur in my poems, but is not their exclusive concept of time. It expresses various things, but the chief among them, it seems to me, at least at the moment, is this. I see that the essential progress is located in the individual person. This is why the people of the past are not inferior to us, even though corruption by technical progress makes it hard now not to believe the lie that we are better and the people of the future will be better still. No, overall progress will only happen to the extent that each person makes personal progress. One of the chief questions over human life is whether we’ll ever achieve a point beyond the steady-state of mixed nobility and degeneration that seems to define every historical era.

The reason for the difference between my way of using narrative and Ashbery’s version of eternal recurrence was my judgement that he portrayed a twilight vision of a world reduced to endless interpretation and to an equal, undifferentiated prominence (which meant, simultaneously, a distanced vagueness) of every element and moment of life and society. Either progress was impossible, both in the society and in the individual, or it was unknowable. What was happening was unknowable. The old scientists and analytical philosophers used to say that we can’t know and anything about God, if there is one, so he effectively doesn’t exist since he can’t exist for us. Ashbery saw that this same impasse existed with regard to all reality including our own lives, except that we could never entirely say we did not know our lives, since we had to get up and do things, people kept acting...at any moment we might die from our lives. Within this he developed what you could call an ethic, a vision of a way of living, which was a floating among the welter of feelings and perceptions, and a learning to accept, even at times enjoy it, including even your own bafflement.

There is profound truth in this. I don’t deny its truth. But for my poetry I wanted something different, in fact the opposite. I wanted to oppose this. To remove it, to change the temper of life, to restore clarity and dynamism. And I know, feelingly, that this was not simply a reaction against the poet I’d come to think of, around 1967, as the great and dominant one of our time. No, it was my own vision and feeling about life and society. Ashbery helped me see that society’s “will to suicide”, in Jacques Ellul’s phrase, expressed itself not only in war and torture and the nuclear bomb, but in a muted despair, a twentieth-century (and now twenty-first century) version of Thoreau’s “lives of quiet desperation”. A near-indifference merged with a sort of dilettantism of enjoyment. It was a version of the aesthetic ethic, as found for instance in Henry James, that Eliot criticizes so strongly in The Waste Land, or a softened version of the “burning with a hard gemlike flame” which was all Walter Pater could find to live for in the late nineteenth century.

JL:

Could you say a few words about how this specifically shows up in the poetry?

AFM:

The poems I’ve placed first in The Sparrow rounds on this attitude I’ve attributed to Ashbery and a certain tradition. It characterizes it with bitter sarcasm. “We Decided This Was All” is its title, and in great though not complete measure the “all” it names is this that we’ve been discussing. The comfortable “we” of culture creators is presented this way:

Elsewhere—in France, in America—men tried to excuse themselves

for being rich and happy. All is madness, they said. We suffer too.

Love takes many forms, all equal: enjoy the brief gift

when times grants you absence of pain.

The encounter with Ashbery threw me back to my earlier view, one which I firmly hold to this day, that the Romantics were the true modern poets, far more relevant to “right now” than later writers, because the essential modern problems, and the essential modern forms of the eternal problems, have not changed, but the Romantics saw into them with amazed awakening, with passion, and thus with complete depth. People since then have successively got used to them, accepted them in the sense of despairingly decided they can never be removed, and have arranged life as living with them, disregarding them. But they can’t be disregarded, so they become background, and are pushed largely into the subconscious, from which they continue to emerge, torment us, dominate us.

Then, towards 1968 and 1969, while still fully engaged with and even drunk on Ashbery, I began to discover and take my stand with contemporaries who maintained the Romantic passion in one way or another, as I aspired to do: Octavio Paz, Yves Bonnefoy, Czeslaw Milosz (I didn’t discover him, really, till the 1973 Seabury Press selected poems with the preface by Kenneth Rexroth), the Neruda of The Heights of Macchu Picchu, and Beckett. I’d first seen Godot in 1965 and already had admired him deeply, but didn’t begin to read everything until 1968 or 69.

Vis-à-vis Ashbery, I set out to admit and incorporate his vision into my own. Mine was a vision of hope, not of certainty or belief. I didn’t see that Ashbery was wrong except in the sense that he could become wrong if only I and others would wake up and change the temper of life. I wanted to recapture the Romantic astonishment both at the fresh wonder of the universe and at the evil man has planted in it, discovered in it. I wanted to recover the Romantic passion to revive feeling, to take things seriously, including the joy of living: seriously doesn’t mean “solemnly”! It means with deep feeling, with enthusiasm. I wanted to go back to the idea of “reason” as something that far transcends rationalism, that guides intelligent action when bonded fully to the feelings and emotions, the “sensibility”. I wanted to champion the imagination that, in their different ways, both Blake and Coleridge had proclaimed with a depth that saw imagination and reason as one and the same. Imagination the reason of reason; reason the means of imagination.

This incorporation of Ashbery occurs in many places in my work. The chief and most obvious one is A Houseboat on the Styx, which is fully a narrative poem, in the condensed epic tradition and with reference to Ashbery’s use of narrative in lyric and meditative poetry. You can’t tell this from The Sparrow, though, since A Houseboat is a book-length poem and little of it is included. I’ll just say that in Houseboat, whose very title was an Ashbery allusion—Houseboat Days—there are passages that purposely diverge into something very like Ashbery’s style and comment upon it. Also I can mention that the character spoken of in the poem—including the fact that it slips between male and female and is a loved one—is Ashbery to a degree. The end of the poem is a sort of olive branch. Ashbery becomes the self-sacrificing, Christ-like figure who has taken on the evil of man in its present-day form, this crepuscular inability to know, and who wanders through the world observing and opening himself to all, restlessly ready to assume the whole burden of not knowing and to admit knowledge if it should appear.

Because finally, although I continued and continue to see the difference between Ashbery and me as I’ve described it, I also came to feel that his work contained an element of going forward, of never giving up, of clinging to at least the ghost of human aspiration—an element I’d scanted in judging him. God bless him. There’s an element in Ashbery of another of my poetic mottoes, Beckett’s “I can’t go on I’ll go on”.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

James Lindsay has been a bookseller for more than a decade. He is also co-owner of Pleasence Records in Toronto, a record label specializing in post-punk, odd-pop and avant-garde sound pieces.