An Interview with Adèle Barclay

By James Lindsay

“I'm not too interested in the reader needing to understand the private language...” - Adèle Barclay

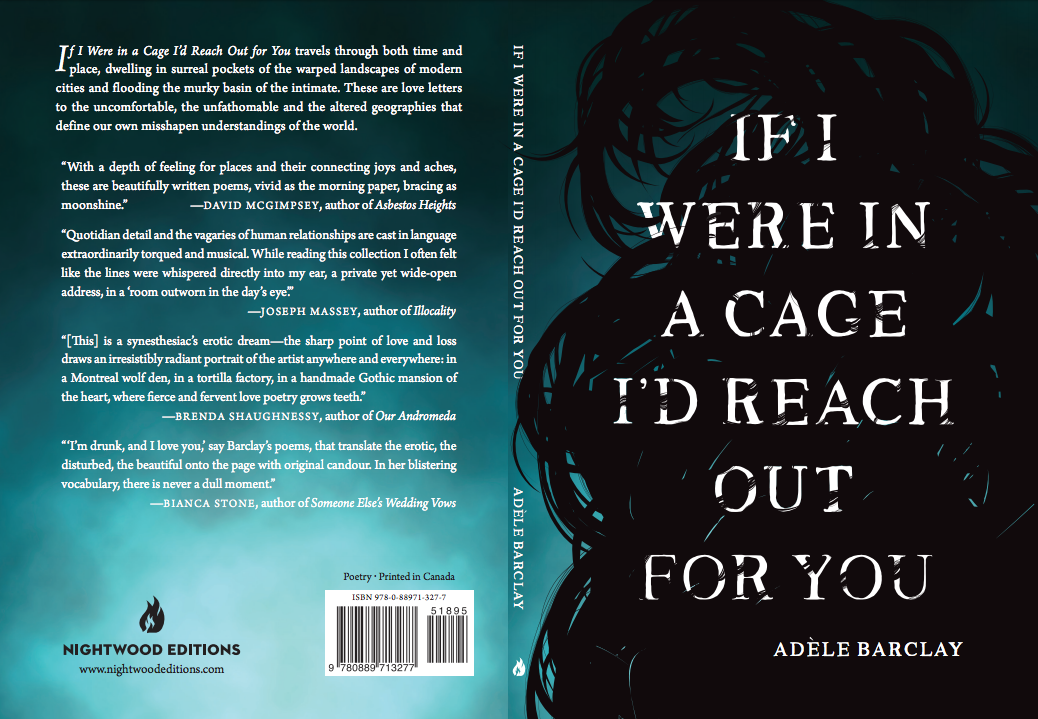

Adèle Barclay’s BC Book Prize nominated If I Were in a Cage I’d Reach out for You (Nightwood) feels like an account of trying to describe something unnamable, that you are surrounded by, but don’t understand, to someone you know very well, but are separated from. You know it’s very important for this person to comprehend where you are and what you see, but how do you make them see what you see; feel what you feel? Barclay’s debut collection tenaciously attempts to communicate that affect of distance and isolation using beautiful, surreal language packed into tightly formed poems.

James Lindsay

Much of If I Were in a Cage. . . feels like correspondence that the reader is eavesdropping in on, especially with the “Dear Sara” serial poems that tie the five sections together. Do you have particular individuals in mind when you write?

Adèle Barclay

It depends on the poem, but many of my poems are overtly, directly addressed to distinct people. I like to write in the epistolary mode because it conjures specificity and intimacy. Poetic language is a place to articulate feelings that escape the bounds of normative correspondence. The poems allow for the complexities that are inherent to our relationships. I'm fascinated by the intricacies of interpersonal relations, how sexual, romantic, platonic strains overlap and diverge. I wrote many of these poems because I had something particular and unusual to say to friends and lovers—or even something that felt beyond language, something akin to energy that couldn't be resolved or contained. And then surprisingly readers have responded strongly to these poems because of their private yet wide-open address.

James Lindsay

It’s not surprising that non-native speakers of these private languages can appreciate their intimacy, but can a reader ever understand it? When you read the work of others like this—in the epistolary mode—what is it that you appreciate? Is it something like empathy? Is it aesthetic? Or is it more voyeuristic?

Adèle Barclay

I'm not too interested in the reader needing to understand the private language of the epistolary mode in order to engage with the poem—just like I'm not concerned about trying to decipher or unlock a poem in general. The mystery is part of the magic. What's compelling to me about the epistolary mode is the heat released with this merging of feeling and form. Empathy is certainly part of it—ideally it draws you into an intimate orbit. Voyeurism could be part of it too. We're used to performing intimacy in semi- and wholly public ways and so the letter poem exists in relationship to the ways we address each other and perform our relationships on social media. I like these kinds of poems because of how they perform vulnerability while taking up this tension between the private and public.

James Lindsay

That's a very interesting point about epistolary poems and social media. Traditionally letter poems would be seen as privet communications that the reader is privy to, but social media has made so many of our communications public. Are there other ways you see social media influence contemporary poetry?

Adèle Barclay

Yeah! I think social media has us honing our personae, which bodes really well for poetry. We perform myriad versions of ourselves on various social media platforms and then toggle through them. And there's a self-awareness in these constructions and uses of the selves—the language gets specific as it correlates to tone. I see this reflected in a lot of younger and social-media savvy poets—they have an incredible ear for voice, fluctuating subtly to great effect. The voice resonates across several registers at once. All of this text-based social media performance pushes poetic personae further and weirder and smarter.

James Lindsay

So when once we had a distinct work-self, a family-self, a social-self—these distinctions are becoming less distinct as we approach a single-self that is displayed online. I’m trying to make a link to what you mentioned about the “uses of the selves” and how it affects new poetry, like a folding of genres. For example, your own work sounds like a single voice but contains large swatches from across different areas of poetry. Are poets becoming unconcerned by what “kind” of poetry they write, unmoored by specific schools?

Adèle Barclay

I think that those distinctions are still there—it's just that those selves seem to hang out together more. Or maybe they always have but social media platforms really accent how those selves converge and diverge. I think that's where the discomfort of Facebook comes from—it's like a really big wedding with your coworkers, family, childhood friends, new pals. We navigate how to address those various groups simultaneously or separately, using language to flag who we're speaking to.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

It's interesting to hear that my poems sound like they have a cohesive voice—I really tried to experiment with form and I tend to stay far away from narrative. But yes, the poems of If I Were in a Cage I'd Reach Out for You travel widely while the voice anchors them together. I can't speak for what other poets' concerns are. I do think schools and influences are still in effect. I know for myself I read widely and I absorb a lot and then try to flag those variant interests in the poems. I'm very concerned about the kinds of poetry I'm writing, where it comes from, who I'm responding to or building from. I like creating space to merge these different groups, splicing schools together and seeing what happens. I do this both in person with friends and while writing poetry. I crave conversation with multiple sources.

James Lindsay

Do you always have this kind of stuff you have in mind before you begin writing a new poem? Or do you ever just start writing and see what spontaneously comes out?

Adèle Barclay

I think what happens is something in between those two extremes. I don't plan out poem and I definitely do write from an intuitive place. Sometimes poems swerve in directions I didn't anticipate. And yet I often feel like a lot of these things exist as ideas or even sensations that are percolating or ambiently swirling around in my poet brain. The writing distills them.

Adèle Barclay’s writing has appeared in The Fiddlehead, The Puritan, PRISM, The Literary Review of Canada, and elsewhere. She is the recipient of the 2016 Lit POP Award for Poetry and the 2016 Walrus Readers’ Choice Award for Poetry and has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. Her debut poetry collection, If I Were in a Cage I’d Reach Out for You, (Nightwood, 2016) was nominated for the 2015 Robert Kroetsch Award for Innovative Poetry and is currently a 2017 finalist for the Dorothy Livesay Poetry Award. She is the Interviews Editor at The Rusty Toque, a poetry ambassador for Vancouver’s Poet Laureate Rachel Rose, and the 2017 Critic-in-Residence for Canadian Women In Literary Arts. She holds a PhD in English from the University of Victoria and researches modern and contemporary American poetry.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

James Lindsay has been a bookseller for more than a decade. He is also co-owner of Pleasence Records in Toronto, a record label specializing in post-punk, odd-pop and avant-garde sound pieces.