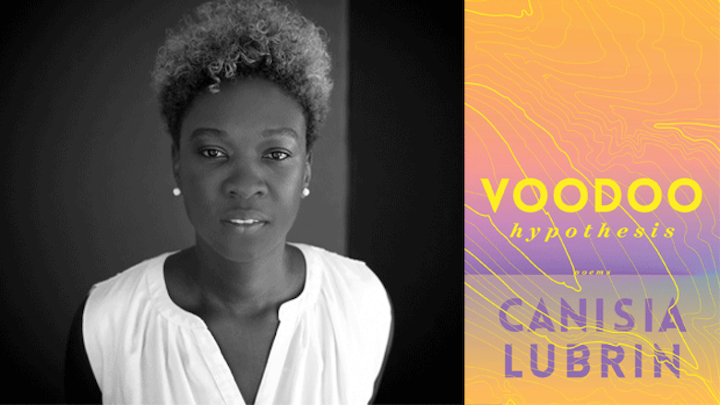

An Interview with Canisia Lubrin

By James Lindsay

“I think memory, or more specifically, history, plays a role in how we understand ourselves." - Canisia Lubrin.

The encyclopedic poetry of Canisia Lubrin simultaneously works on intellectual and cerebral levels with such subtly and grace the reader might feel that there was never a division at all. Born on St. Lucia, her early childhood plays a significant role in her work, both in memory and ancestry. One can hear a storyteller in the rhythms found in her debut collection, Voodoo Hypothesis, possibly leftover from listening to her grandmother’s folktales, but one can also hear a determination to tell her own story. Her challenging but highly rewarding work offers a spectrum of emotion, history and urgency that feels uniquely specific for our times.

James Lindsay:

Certain names make several appearances in Voodoo Hypothesis, both in quotes but also in the poems themselves to the point where they almost become characters. Derek Walcott is the most prevalent, but Roseau and Caruso reappear throughout the book. Can you comment on the repletion of these names?

Canisia Lubrin:

Derek Walcott's "What the Twilight Says" served as a kind of sounding ground for some of the thematic concerns in Voodoo Hypothesis. I suppose every poet of Caribbean lineage today owes something to Walcott and exists in a poetic tradition that Walcott was instrumental in helping to create. The same can be said for others: Césaire, Glissant, etc.. In that sense, I believe, it is good to draw lines between discourses on route to finding your own. So, here, I am immensely grateful even though my intellectual space in the book is critical. For this collection, I rely on Walcott's criticism for how it untethers me from commitments to intellectual hierarchy; I find the idea of intellectual modes more helpful and more real. This helped me settle into a finer appreciation for the frictions that I explore in the book through transnational, multi-historical, and even futurist shelters of experience, which, to me, is a more accurate representation of the manifold realities of diasporic life.

I use both Caliban and Crusoe to interrogate the meanings of selfhood, power, and Black otherness in the proverbial West. The traditional reading of Daniel Defoe's "Robinson Crusoe" in this sense contextualizes servitude in terms of a benign hierarchy. Whereas, Shakespeare's Caliban is traditionally read as a site and subject of complete subjugation. My impulse was to find the difficult agency in both of these imaginings of "the slave" that allowed me to explode this idea of benign hierarchy in interesting ways. So, having Crusoe and Caliban resonate through some of the poems either in conversation or in contrast was a way to explore the contemporary meaning of Black being/nonbeing in the West.

I am from Jacmel, a small hillside community in the Roseau Valley in St. Lucia. And even though I lived there for only eight years, the place forms huge swathes of my imagination. I'm also speaking to, through, and against some degree of home as disenchantment, interrogating a kind of severing from your personal history, the traumas and exigencies of exile.

JL:

That reminds me of a line from the title poem that also opens the book: “But why should I unravel over all this remembering?” Both the length and density of information in these poems convey a feeling to me of actively doing a lot of memory work, of the labour of reaching back and taking time to consider the depth of what you found. Was the writing of Voodoo Hypothesis explorative, did it have surprises, or did you know where it was going to lead you?

CL:

Well, this book was a series of surprises, an exercise in trusting my instincts and then subverting the expected because this is the great agency of the colonial subject: to live in spite of being objectified. I think memory, or more specifically, history plays a role in how we understand ourselves. What also bears attention is what arises when a thing is emptied of its historical significance, either by ascribing false value or denying value. One thing is things can lose some semblance of truth. But those responsible for the history that has been prioritized were invested in a kind of world-building that eschews things towards their own positives. And when most people think of history they mean the catatonic thing tethered to linear time. For me, history as it is taught and learned is not a static thing. I don’t believe in singular history; if I did there’d be nearly no place to find myself in that typified reading of linear existence outside of the pure victimization that we know as part of the dominant Black Western experience. In order to center narratives that work against the imperial construct of Black peoples as inferior, I had to reach back for pre-colonial events to resonate into the present. But the biggest thing for me is to honour poetry as something which itself is not tethered to time. Poetry can exist in the past, present and future all at once. But this work specifically required that in order to have any sense of what is possible, I had to start with what there is to remember… so it was in all ways exploratory.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

JL:

You don’t have to look farther than the recent John A MacDonald school naming controversy or the protests in Charlottesville to see the anger that arises when traditional historical narratives are challenged. Is progress being made when it comes to reexamining singular history or is the anger and violence overshadowing any progress?

CL:

Here’s the thing about change: it comes always at a cost. The need for actual progress to match optics of frictionlessness is another register of the need or preference for singular narrative/history in itself. What’s involved here leads to something which is as naive as it is false. I think the thing that often gets lost in these debates is how attempts to make room for other social subjects, histories and people in our broader narratives, especially in arenas that are overcrowded with painful reminders of what those subjects have had to suffer in order for the dominant narratives to thrive, is the fact that what is at stake is far bigger than any anger that those revisions can incite. People of colour have always found ways to exist and to live and be productive in spite of our subjugation. The resulting dissolutions and corrections that come with challenging singular history do not mean that our problems disappear; they mean that, rightfully, the stories of our Indigenous and Black and Asian folk that have been deliberately obscured or made invisible can also be at the fore. So I return to this sense of progress as unstable. Has there not always been progress, whether or not these continuums were or have been recognized as such? To be clear, the majority of Western cultural production has come from those continuums of personal and community progress that have been co-opted and have had their sources (marginalized communities) erased.

JL:

How does Voodoo Hypothesis challenge the dominant narrative, the singular history? And what are poetry’s strengths when engaging with social-historical injustice?

CL:

I’ve said elsewhere in detail that I intended to interrogate what constitutes western ideas of The Other as a way of delineating its dominance in attaching value to Black lives. When I say this, I mean I reject things that have historically and continue to contemporaneously prohibit, exclude, silence and erase Black people—particularly those who descend from slaves—from anything of “worth” in the western world. We know this story. It’s a cliche by now. And one doesn’t have to work hard to find iterations of this in everything from our most elitist education systems to the popular culture that seems the stomping ground of everyone. I think my modes of challenging singular history in the collection are perhaps some of the most self-evident things about the book. I forage the systems that the western world was built upon: religion, culture, science and fake-science, capitalism, literature, etc. for things that reveal discordances or fault lines that I could then subvert in my thinking about this business of othering. I think poetry is a heck of a chameleon of an art form. It can’t be tethered to singularity but it operates through particularity. What makes poetry such a badass is its multivocal, world-bending ability to express things that often escape expression. The work of poetry is beauty and clarity and possibility by way of language. I’m not willing to reduce this to theory or simply to aesthetic servitude towards some end. I believe in language and letting language do its work—whatever this is, which isn't entirely up to me, the poet.

JL:

In a recent interview with CBC you spoke of remembering your grandmother and spending your early years on St. Lucia. Obviously these were hugely influential on you writing, but I was also struck by how prominent memory is in general when it comes to your writing. When you write do you always feel an element of “reaching back”?

CL:

I think that in our dominant literatures to some degree, memory, like history, is a thing that has lost some significance in our time. I remember Dionne Brand saying that the poet must earn their use of things like memory and love and those big ideas in their work, that the poet must work hard towards their own, precise and particular expressions of those things that can so easily fall to cliche. This has always stuck with me. So, you’re right. My grandmother’s storytelling figures significantly in my writing life. These oral traditions that I speak of in the radio documentary depend on memory. You don’t read those stories, you recite them. There is something infinite yet immediate in that act of fusing story to memory; it is embodied in the mouth, worlds traveling in the breath, in the heart and mind. The human can’t be separated from this mode. And because of this, storytelling in this way to me is even more powerful. Story in this mode, then, is no theory; it is lived, irrevocably personal. I think, though, generally writing is the work of remembering. I will also add that linear time is a very problematic concept. Whether we remember forward or backward or whatever has probably more to do with the particular work, what it needs, what it is trying to do.

JL:

How did you divide the poems into the five sections of Voodoo Hypotheses? How do they differ to you?

CL:

The sections are arranged thematically. They’re each doing distinct things, though ultimately, they should build toward a coherent vision, which is to trouble these ridiculous ideas about the other. I know I am not guaranteed this outcome, which is completely within poetry’s purview. But each of those themes (memory, exile, inheritance, the body, myth) are offered mainly through considerations of time and ideas that are tethered to these particular epochs. The primary consideration is my modes of inquiry as I move from the past to the present to envisioning a future.

JL:

This is your first season as co-host for Pivot, one of Toronto’s most beloved reading series. What does it feel like to take over such well-known event and where do you want to help take it in the future?

CL:

It is a big responsibility. And my lovely co-host, Michelle Brown, has been tremendously good in helping to keep CanLit’s beloved Pivot going. I suppose the thing about community programming, which I’ve done for close to two decades, is that you must be plugged into what is happening organically within the community in order to respond accordingly. We plan to keep doing what people want to come out to see and enjoy. And, of course, to do it in the service of literature as it keeps moving forward.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

James Lindsay has been a bookseller for more than a decade. He is also co-owner of Pleasence Records in Toronto, a record label specializing in post-punk, odd-pop and avant-garde sound pieces.