An Interview with Shazia Hafiz Ramji

By James Lindsay

“My Instinct was to Listen and Notice in Order to Survive.” - Shazia Hafiz Ramji

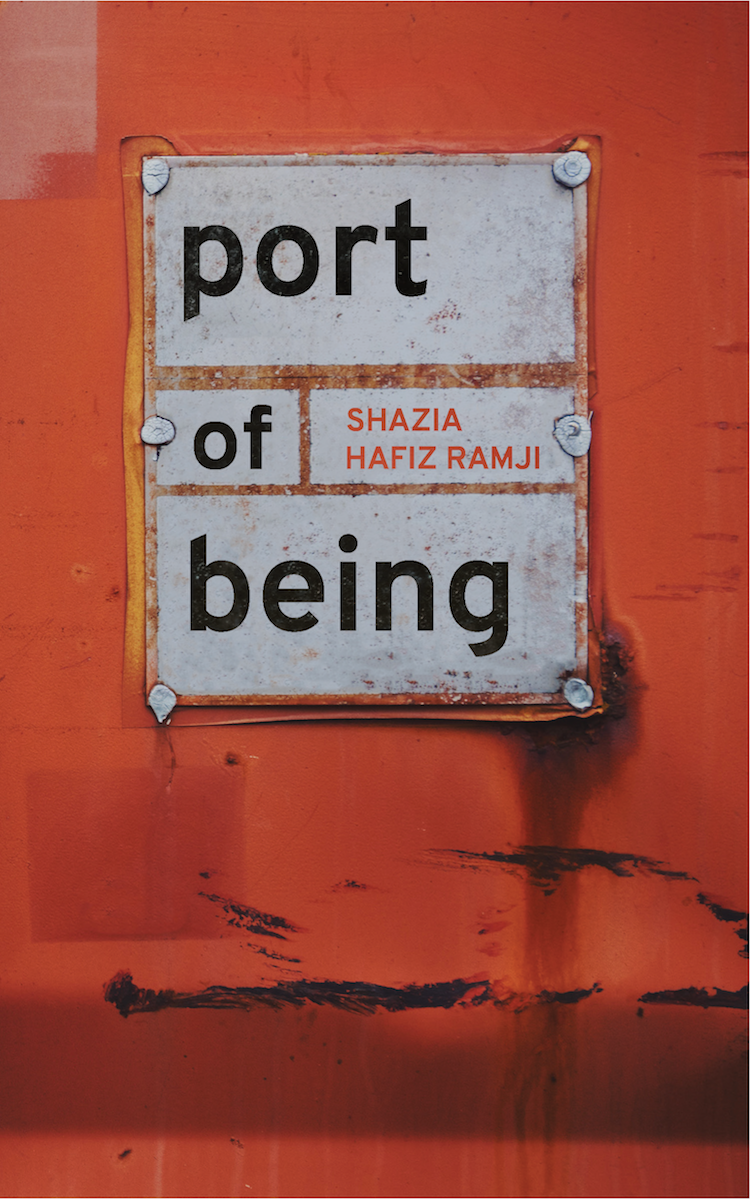

In her debut collection, Port of Being, Vancouver poet Shazia Hafiz Ramji manages to take the personal and make it into something globally minded. Inspired by her own trauma, Ramji turned her focus outward to begin to process what had happened to her, giving these poems a wide yet tender gaze. Port of Being imparts the sensation of sitting in a space and observing the world around with sensitivity and a longing to hear the stories that pass by. But whether this space is public or private seems unsure. In an age of social media and twenty-four hour news cycles, the lives of others can easily bleed into our own as we take in information so casually it becomes invisible, watching others as we are simultaneously watched ourselves. Port of Being takes these everyday acts of voyeurism and makes them feel intimate but still engaged with the outside world.

James Lindsay:

Social media, surveillance, and global shipping are all at the forefront of Port of Being, giving it an immediacy that I also read as somewhat cautious of modern communication and skeptical about technology’s ability to connect us. So I wonder, how did you see these themes connecting as part of the collection and was there an impetus for the poems to be as current as possible.

Shazia Hafiz Ramji:

The themes in Port of Being emerged gradually over time, but they are all connected through a process: walking. For some years now, walking the city has been really important for my writing. I often go on dérive walks where I wander without a destination in mind with the hope of being surprised by other people and seeing familiar sights and sounds in strange and new ways.

When I was writing Port of Being, I had left my job as a poetry editor at a local press. I was reeling from workplace harassment and bullying, and I left in the wake of that. I was depressed and broke (I’m not using the words “depressed” or “broke” lightly or in colloquial way, as people sometimes do). I came to the themes of surveillance, shipping, and social media out of a desire to feel at home in the world; walking had become a necessity to prevent isolation, depression, and addiction, experiences I’ve lived through in the past and that I was living in fear of at the time.

I knew from recovery that I had to move outwards instead of inwards; into the world and others instead of myself, so I began listening to the words and lives of others as a way to keep living. The news was one way into that as it captured a larger sense of story and history, while walking the city was another way that moved me towards the history of the everyday. I think these two approaches may be the reason why these poems seem “current,” but when I was writing them, I felt a kind of timelessness in a strange way, as if the people who inhabit the city are a palimpsest of many times and places including those that have preceded us. My instinct was to listen and notice in order to survive; I put myself back into relation with others by walking.

Theory-wise, the dérive formalized my process of walking and wandering, and it enabled me to forge a poetics of relation. I was asking myself questions like: How is my body cartographing experience in the city? What do surfaces and speech tell us? Can a phenomenological approach capture the lyric subject in relation? What would a lyric subject look and sound like right now? How is the “I’ constituted in a globalized, modular world? Can there be a modular lyric? What would it take to get to a place of “sincerity”? Are facts sincere? Is a documentary poetics possible from the perspective of the flâneuse?

Gradually, I saw that these poems were thinking through the relationships between people and objects (such as cameras, containers, drones, satellites, space junk etc.), as well as the city. So, surveillance, shipping, and social media are connected in the sense that they are parallels, being objects and technologies that mediate our movement, experiences, and interactions with each other.

Even though it may seem as if there’s a straight line between the dérive, poetics of relation, and the book coming into existence, in reality Port of Being grew through a slow process of city walking, obsession, and working through trauma. The larger themes of surveillance, shipping, and social media are rooted in two lived experiences that are the inciting events for the book. The first one is the experience of being stalked by a thief, and the second one is the subsequent experience of carrying out my own surveillance along the waterfront by means of listening and noting bits of overheard conversations.

JL:

Many people talk about feeling their depression and fatigue from news consumption these days, so it’s interesting you found solace in it. When looking at Port of Being now, do you see that difficult time in your life or does the media you consumed around than obscure it?

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

SHR:

What an interesting and difficult question! When I look at my work, I definitely see that difficult time in my life, but I’m unable to see it as separate from the media and news that were not only vehicles for its telling but a crucial part of the fabric of my experience, although on a larger and more intricate scale. Though, I’m also aware that this difficult time in my life might not be visible and obvious in the poems. I was “telling it slant,” following the approaches of W.G. Sebald, Emily Dickinson, and Teju Cole, and only much later, I saw that I was working through trauma for sure. It took me a long time to confront the trauma (I’m definitely a pro at repression) and I was only able to accept it after my mentor and professor, Ian Williams, suggested that I was working through it. However, I wouldn’t say that I chose to tell it slant as a result of trauma – it wasn’t a choice.

Part of the reason I approached the book the way I did is because I believe (very strongly) in being receptive to what’s around me to find a way into the poem. Being attentive to the world through the news and listening to others in the city moved me out of the way of myself, and I feel that I wouldn’t have been able to write this book if I didn’t believe that. When I look at Port of Being now, I see an arc in it, with the first few sections being more fragmented, newsy, modular, leading to the last couple of sections, which confront the more difficult aspects of my life in a more lyric mode.

JL:

The third section, Flags of Convenience, stuck out in particular for me. More so than just being newsy, it deals with the lesser-known tragedies of global shipping that rarely make the news, especially in terms of the effects on the crew themselves. Even the structure for these poems stands out from the rest of the collection; they feel looser and have a drift to them. What brought you to write about shipping and for you how does it relate to the rest of Port of Being?

SHR:

I think I came to write about shipping because I live in Vancouver and the port is full of containers and container ships. Generally, the world of ships is one that I’ve been connected to on some level. My ancestors sailed the Indian Ocean and Persian Gulf, so I’ve always felt a connection to and curiosity about ships, boats, the ocean, and here I was in Vancouver, witnessing and sensing the many layers of history, time, and space that overlap and intersect, especially along the waterfront. I couldn’t not be drawn to it. Sometimes in the colder months, I stay up until three or four a.m. just to hear the foghorns!

During research, I became fascinated with the history of containers. They are multi-purpose, interchangeable, and impenetrable steel boxes in the chain and assemblage that is shipping, and they completely changed our relationship to time and space. I had never thought of how important they are. I mean, a lot of what we buy off the shelves at supermarkets comes out of a container! Drugs too. People too.

I found out about flags of convenience when I stumbled on an untitled PDF document about “accidents at sea.” It was made of reports about the labour force employed on container ships: men who couldn’t speak English fluently, such as Polish and Filipino immigrants. Sometimes they weren’t paid at all. Sometimes, when the ship was stranded, they would be left alone without food and water. Sometimes they mutinied. People died, ships sunk, burned, or were abandoned. The reports tried to give reasons in detached and efficient language, and I couldn’t stop feeling the silence of the workers’ voices. Can you imagine the entire edifice that makes something like this possible? The ship often originates in a wealthy country that employs immigrants from vastly different countries, and then uses a flag of another totally different country that is often poor – to evade safety regulations and financial charges. I cried. I felt a sense of responsibility to untold histories and facts when I was writing “Flags of Convenience” and I was attentive to the conditions of colonized countries and immigrants’ struggles. All of this loops back into an obsession with the way technologies have changed the perception of time and space for us, and what that does to our lives, and the ways our bodies respond, move, and interact with each other through and because of objects (like containers).

JL:

In the notes section of Port of Being you mention discovering Vito Acconci’s Following Piece, a work of performance art in which he documented following strangers on the streets of 1969 New York City until they entered a private space, like a building. You write that you were, “Simultaneously emboldened and angered by Acconci,” before embarking on a bit of light surveillance of your own that helped relieve depression caused by the stalking and that inspired the opening section, “Container,” which uses overheard conversations. Could you elaborate on what you found emboldening and angering about Following Piece and how it helped you?

SHR:

When I first discovered Following Piece, I was rapt. I couldn’t believe that Acconci followed people – sometimes for hours at a time on the streets of NYC – for a work of performance art! And then I was angry; the position of the voyeur and flaneur has traditionally been occupied by a male gaze, and this was yet another example of that. Despite my anger, I was relieved to find Following Piece. When Acconci performed it, he was stalking people for sure, but he said he also gave up his own control because the person he was following dictated his movements! I hadn’t thought of the vulnerability of the stalker in this way. It incited a deep curiosity and allowed me to confront my dual position as a victim of theft and stalking and as a low-key flaneur-voyeur myself (being a writer who always indulges in people-watching and overheard conversations).

Most of all though, Following Piece helped me work through the trauma of being stalked by a thief who called and tried to see me for months afterwards, and on top of everything, I had quit my job and was broke. I was living in fear of myself, trying to prevent depression and relapse. In the past, making field recordings and listening to music helped relieve these experiences, and this time when I was too depressed to be able to enjoy music, Following Piece gave me the perfect constraint. I began listening attentively again, as I had done in the past. Only this time, I followed people along the waterfront as they moved through semi-public spaces, like a cafe patio or a store entrance, and I noted the words they said in these spaces.

Sometimes, people spoke of things being out of place, like a fishing boat that wasn’t supposed to be there. Often, people spoke of not having enough food, money, clothes. I also overheard a conversation about someone whose friend had tried to cross from Calais to the U.K. as a stowaway. The little glimpses of people’s lives through their words allowed me to overcome my own suffering, if I can say so. It was very humbling.

Following Piece really showed me how the space of the city and the port shapes not only our relation to each other, but also our bodies – how they move and feel and what they do within certain boundaries and gazes.

I’m constantly seeking work that challenges and consoles me all at once, and Acconci’s Following Piece was exactly this. In retrospect, the timing of discovering Acconci was impeccable. It led me to the entire book. I almost feel as if discovering FP at that time in my life was a gift in some way.

JL:

It seems as if the writing of Port of Being was a transformative experience for you. Have you written much since completing the collection? I wonder if you’re planning a new project and if you have a similar theme or focus in mind, or if you let the poems emerge on their own and make sense of it later.

SHR:

It was definitely a transformative experience. I don’t know how I would be who I am now if I didn’t write it.

I’ve written short stories since, most of which have themes that are very present in Port of Being. One of the stories, “Pilgrims,” is about a solitary girl, who is a recovering addict. She works in surveillance and has to leave an increasingly violent, co-dependent relationship before it gets worse. It was one of the first stories I had the guts to send out and it received an honourable mention in The Humber Literary Review’s Emerging Writers Fiction Contest, judged by none other than Cherie Dimaline and Ayelet Tsabari! I was irrationally desperate for this story in particular to be out in the world. I felt as though I would be free in some way if it was received by others.

Currently, I’m working on a novel that has been brewing for a long time, and through it I’ve been trying to understand my own addiction and recovery, but it has grown to include my ancestors, which means there are going to be lots of ships if it continues this way... I wasn’t expecting to end up in historical territory, to be honest. I feel as though I’m driving a car on a very dark and winding road, and the only thing I can see is the patch of road in the path of the headlights … sentence by sentence. Then again, I don’t drive, so who knows what I’m talking about? I guess this means we are in novel-in-progress territory.

And because I can’t help but build labyrinths for myself, I’m working through the novel by writing poems, so this also means I’m working on a second book of poems! I’ve taken to city walks and flanerie again, like I did with Port of Being, and the poems are congealing cohesively, but I’ll stop myself from labelling the “aboutness” of them yet, in case I kill them by doing so!

I’ve also been making field recordings to get into the zone I need to write the poems (and because I enjoy it)… but that is the last turn in the labyrinth – I hope!

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

James Lindsay has been a bookseller for more than a decade. He is also co-owner of Pleasence Records in Toronto, a record label specializing in post-punk, odd-pop and avant-garde sound pieces.