An interview with Jaime Forsythe

By James Lindsay

“How I fit myself into my work is something I’m still figuring out.”

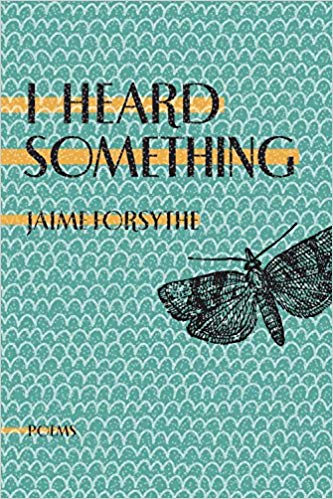

Jamie Forsythe’s I Heard Something finds mystery in the common place. Domestic scenes take on a surrealistic quality as the daily business of being a parent scrolls by. These poems excel at not necessarily warping the regular into something strange, but rather discovering absurdism that is in plain sight, disguised as the mundane. Likewise, memory and its precarious nature frequently bobs up in this book and the effect is like repeatedly looking back at a moment and becoming aware that it changes each time it’s viewed. What is taken for granted gains a haunting quality that still manages to find humor in itself. As a new parent myself, I selfishly had to start by asking her about how it can change ones writing.

James Lindsay:

There is a lot of parenting happening in I Heard Something, but it appears in a kind of observational collage. Visits to science centers, natural history museums, and hurricane simulators take on a pastoral quality to them. I bring this up because, as a new parent myself; I wonder how becoming a parent influenced or changed your writing?

Jaime Forsythe:

Congratulations! That’s exciting. I think children and childhood would have appeared in my poems regardless of whether or not I became a parent, but you’re right that those backdrops show up in this book because I was spending a lot of time in them, or being reminded of time spent in them when I was a child myself. Their often strange, evocative details felt potent to me, especially experienced through the hazy, slow, floating quality that time takes on when you spend many hours with a small child.

I was curious, and maybe a bit worried, as to whether writing and reading might not seem as important to me after becoming a parent, or that I wouldn’t have the mental space or capacity for concentration to prioritize it anymore. I think mostly, I wondered/worried if my compulsion to write might disappear, for a few years or forever. I think everyone experiences the shift differently, but for me personally, this was not the case. I felt an almost panicked urge to scribble things down in the earliest days of being home with an infant, and remember balancing my notebook on him while he nursed. I’m not saying I was writing anything very good or interesting during this time, but the action itself felt necessary as a kind of survival tactic. Because of course in addition to having many truly lovely and unexpected moments, days upon days with a newborn can also be isolating, tedious, and overwhelming. The same was true of reading: I wasn’t able to read for very long uninterrupted, but I reached for small bits of poetry and fiction to pull myself out of the drearier moments and feelings. I read Rachel Zucker, Lorine Niedecker, Katherena Vermette and let the Dr. Sears book gather dog hair under the couch. The associative logic and non-linear nature of poetry, especially, felt like a roadmap and a way to stay connected to that part of my brain.

On a practical level, it can be tricky to find the space and time, for sure, but I’ve also become more efficient. When I do get a couple of hours, I don’t spend it paralyzed by self-doubt: I can multitask and doubt myself later! Writing is difficult but not really more difficult than it was before. I should say, too, that no one writes a whole book while nursing; I wouldn’t have been able to complete a sustained writing project without a supportive partner and family and childcare, and I’m privileged to have access to those things.

JL:

I love how you describe the quality of spending many hours with a small child as hazy, slow and floating. I can already feel certain vagueness to these days. It makes me think of I Heard Something’s title poem, and its’ friend that lives on the page next-door, “Who is Missing, Who is Missed.” Both these poems are searching. “Who is Missing. . . “ by relentlessly asking unanswered questions and “I Heard Something” by doggedly hunting for the source of a sound that’s never found. I wonder if you paired these poems together on purpose or if it was a happy accident? And what brought you to write poems that were so directly asking about and hunting for things they could never have?

JF:

I ordered the manuscript in a mostly intuitive way, by printing it off, spreading out on the floor, and moving it around like puzzle pieces to come up with a sequence that made sense in my gut. The poems were mostly written as individual pieces, without an order in mind, though the two you mention likely ended up as neighbours due to my subconsciously linking their themes when it came time to put it all together. In terms of the question asking, hunting, and searching: I feel like these verbs get at the root of the state I’m often approaching writing from. A poem might begin from a place of trying to figure something out, or make it clearer or sharper to myself. I don’t think the poems arrive at solutions, but they allow me to move and stretch inside a question for awhile, or to add shades and dimensions to my not-knowing. The term ‘doggedly’ feels pretty apt because I don’t feel like I am doing anything particularly special when I’m writing, except maybe being persistent.

In terms of those two poems specifically: the “Who is missing…” poem came out of a dissatisfaction with the questions that are commonly asked or not asked about people, and pushing against that. The most literal aspects of the title poem came from a hypervigilant state I found myself in after having a baby who cried a lot, and often, for many months, and then gradually didn’t so much, but I kept hearing him. This auditory hallucination felt tied to other unexplainable ways that bodies betray us or lead us in certain directions.

JL:

Outside of the relation between these two, were there any other connections or themes you were surprised by when sequencing the poems? I’ve always thought the practice of physically laying out all the pieces of a collection in front of yourself has the potential to reveal something unconscious you may not have been aware of before.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

JF:

I knew that I was writing towards tones and atmospheres with this book, and that I hoped to draw these out a bit with the order of the poems. Laying out the pieces made the fact that it had three sections clear to me: I think of the first section as the most otherworldly, with the voices speaking from the most tucked-away corners of my brain; the second the most located in or wrestling with the past tense; and the third the most forward-looking. I wanted the first two sections to end on notes that felt like unraveling or coming apart, and then for the book to end with, if not a bow, a more gathered-together feeling. I understand that all of this is pretty ephemeral, and whether or not it succeeds is up to the reader rather than me. A lot of poetry collections I admire have an arc that seems to move according to mood or psychic states, and that was in the back of my mind as I edited. I think the threads that emerged were not necessarily surprises, though it was a relief to see that (it felt to me like) the poems were speaking to each other: in terms of the sensory, dreams, bodies, mystery.

JL:

I Heard Something certainly builds to that “gathered-together feeling.” I don’t know if I would go as far as describing the poems as confessional, but they appear to be examining something personal. Parenting, as we discussed, but also something else more abstract. For example, the three poems titled “Autobiography” seem to be more past-reflective; and the first poem of the third section, “If Lightning Was A Thing You Could Plug Into,” begins with the line, “My biography keeps shrinking.” How do you fit yourself into your work and what, if anything, do you want your reader to take away from it?

JF:

How I fit myself into my work is something I’m still figuring out. I think I had to unlearn what I was often taught about writing in undergraduate workshops, which was that appearing in your own work was kind of distasteful. For awhile I wanted to write something that had no visible attachment to myself, that no one would have been able to tell was written by me if it didn’t have my name on it, and that felt very uncomfortable. At 19 I was trying to write in the voice of a 40 year old white man who had lived a different experience than the one I was living, who didn’t show too much emotion, iceberg-style. This feels a bit silly now, but the messages I was absorbing at that time were: this kind of voice carries weight; what this voice says is true.

Now I feel much more at ease experimenting with the personal. I’m drawn to the elasticity of an “I” speaker, and how it can accommodate shifting perceptions and moods, hold contradictions, and take leaps: it can speak directly, step into the shadows, and then return to directness again. Sometimes writing from a first-person voice feels vulnerable, but sometimes it feels powerful, or theatrical, or like singing (if I could sing).

I’m interested in the confessional, but particularly in the ways it can intersect with the surreal – the mixture of the two is what tends to feel the most ‘real’ to me. Sometimes I’ll write a line that is literally true, that happened, and it sounds completely absurd or unbelievable. I find that taking confessional elements and bending or warping them gives me lots to play with, in terms of language, sound, and how to represent a sensation or a scene, how to try and make it vivid. The three Autobiography poems definitely come out of that overlapping confessional/surreal zone, and also a desire to investigate details or that might be prone to getting dismissed or erased.

In the “If Lightning…” poem, I was thinking of the tension between giving parts of myself away and self-preservation. I think that’s a tension I encounter in writing, but also in relationships, work, parenting, etc. I’ll probably be working on that forever.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

James Lindsay has been a bookseller for more than a decade. He is also co-owner of Pleasence Records in Toronto, a record label specializing in post-punk, odd-pop and avant-garde sound pieces.