Behind Every Story, A Less Interesting Story

By Ben Ladouceur

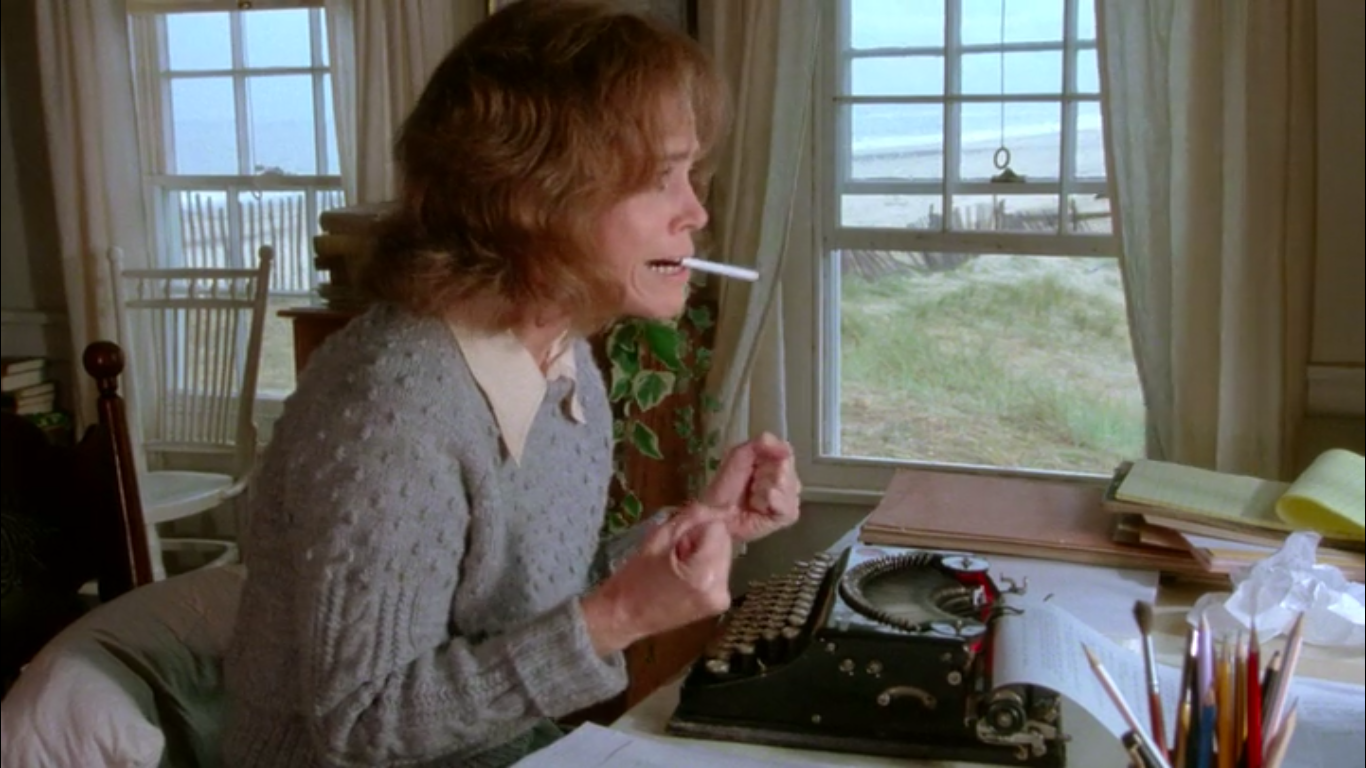

Lillian is trying to write a good play. When progress alludes her, she tears the false starts out of her typewriter, scrunches them up into balls, and kicks over the wastebasket that brims with bad drafts. When her struggle proves real, she holds her cigarette between her teeth, clenches her fists, and screams. She throws her typewriter out the window. She moans in agony. She is alone in the room. This is a scene in a movie called Julia. The montage of her creative frustrations concludes with her throwing her typewriter out the window.

I own a typewriter and sometimes I use it. If I grew so frustrated with my writing process that I threw it out the window, I would immediately pause and reflect at length on my behaviour. Maybe I would call my partner or my mother and recount what I had just done. I would probably Google my symptoms and diagnose myself with chronic stress. I would employ tactical breathing and evaluate all of the choices I made that brought me to this action.

The writing process is blank-faced and very still. If the café patrons currently seated all around me had to guess what I was doing on my laptop, I don’t think there’s any particular “tell” to give away the fact that I’m writing about my thoughts and feelings. I look the same as I would look if I were completing budget spreadsheets, catching up on emails, or reading the news. I might be emoting on paper (or Word doc), but you wouldn’t know it by the sight of me. The most intense physical reaction I have had to the writing process was probably when I typed “THIS IS GARBAGE” at the end of a short story that wasn’t working out. Before hitting Ctrl+Q, I hit Ctrl+S, so that a future version of myself would see how certain I was that my time had been wasted that day. This was quite dramatic. It was not as dramatic as throwing my laptop out the window.

Erica is struggling to write a good play, too. For Erica, it’s going quite well. She is sobbing uncontrollably, but that’s how you know that her play is coming from the heart, which is raw and recently broken. She weeps and wails over the course of a montage, her fingers operating her laptop all the way. Her play becomes a Broadway success. This time it’s a more recent movie, Something’s Gotta Give.

This phenomenon of outlandish behaviour during the writing process is not limited to playwrights. In movies and television, numerous poets, novelists and epistolary writers chomp their teeth, stop and gasp, shake their heads, and emit world-weary sighs while hunched over stationary or keyboard.

Cinema is no stranger to dishonest depictions of basically everything – six-month-old babies arrive in operating rooms, bartenders don’t request specificity when patrons ask for “a beer,” and for drivers, watching the road is optional. Cinema is a world of shorthand. But the depiction of the writing process as something outwardly emotive or physically strenuous has always struck me as especially suspect, and especially damaging to those outside of the know.

Wildlife photographer and travel journalist Robert Kincaid puts it well when explaining his craft, photography, to someone who has asked to watch him as he works: “You’ll find it pretty boring. At least other people generally do. It’s not like listening to someone practice the piano, where you can be part of it. In photography, production and performance are separated by a long time span. Today I’m doing the production. When the pictures appear somewhere, that’s the performance. All you’re going to see is a lot of fiddling around.” Writing is also a lot of fiddling around.

Kincaid is not alive today and never was. He’s the main character of Robert James Waller’s novella The Bridges of Madison County, which was also adapted into a film. In this passage – and many others – Kincaid serves as a sexy mouthpiece for Waller’s thoughts on the artistic process. (The person doing the asking is a bored housewife transfixed and seduced by this mysterious man-about-globe.)

While Kincaid freely advocates for the boringness of production in the non-performing arts, his author, Waller, struggles to put this philosophy into practice. The novella begins with a preface explaining how his book’s story came about. Waller says he was contacted by two siblings who discovered their dead mother’s journal, as well as photographs and correspondences and publications that corroborated the journal’s steamy contents. The siblings, having read and enjoyed some of Waller’s work, called him and insisted that he meet them in Madison County to study the whole archive of their mother’s summer love affair with Kincaid.

These Iowan siblings, too, are not alive and never were. It’s a set-up for the story that will follow, making the stakes of the story feel higher than in clearly-fictional fiction. But Waller is quite desperate to convince his reader that this all really happened, writing elsewhere in the preface, “Preparing and writing this book has altered my world view, transformed the way I think, and, most of all, reduced my level of cynicism about what is possible in the arena of human relationships.” It’s likely that, writing at a time when there were more people living in the Netherlands than there were people connected to the Internet (the early 90’s), Waller hoped that many readers would take him at his word, believing in the siblings and in Kincaid and in the remarkable effect his, Waller’s, research has had on his own worldview.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

This flirtation with deception reminds me of a more recent bestseller, Yann Martel’s Life of Pi, the preface of which details Martel’s listless global search for the seed of a novel. His long-longed-for story finally arrives wholesale in Pondicherry, India, when an elderly man tells him a story that should make him believe in God. This promise – packaged effectively in a plausible anecdote – is then made to the reader of the novel that follows. Martel “retells” the true story that was related to him, complete with a coda that retells the story yet again, in a transcript that the author claims is verbatim to a real recording. Martel’s story, too, is bunk but fun. There are animals and the ocean and, of course, a young man named Pi.

To my knowledge, the most extreme and most satisfying example of this phony-preface trope is committed by Minae Mizumura in A True Novel, a beautiful behemoth of a book that I read last year. I had just finished a stint as a peer assessor for a funding selection committee, and I was sick of reading first chapter after first chapter after first chapter. I wanted to stay in the same book for hundreds of thousands of words. A True Novel’s preface alone is 167 pages, all fiction that the author frames as truth. Just as Waller was allegedly told the story of Kincaid over a few days’ visit in Iowa, and Martel was allegedly gifted the story of Pi over dinner in India, Mizumura claims to have been tracked down in California by a young Japanese man and told the most fascinating story of her life over the course of a rainy evening. When he finished telling the story, Mizumura “was in shock,” at once scandalized by its dramatic sequencing and excited by the fact that her next novel’s plot was already laid out for her. She ends her preface by clarifying that she is not changing the name of her protagonist, Taro Azuma, because “any Japanese person who had lived in New York for any length of time would know who it really was, anyway.” Although the 700 pages that follow this disclosure pulse with verisimilitude, Taro Azuma is not alive and never was. (While I ruined the plots of my other examples a little, I won’t say a word towards Mizumura’s extravagant masterpiece, the better to tempt you to seek it yourself. Save the preface for a rainy weekend.)

I see this as a clever blasphemy adjacent to the camera tricks I described earlier. Like directors staging tantrums at the typewriter and lamentations at the laptop, Waller, Martel and Mizumura (and Ingo Schulze, and Nabokov, and Styron, and many other authors) want us readers to believe that their story is more than an internal process – that it involved something more than just sitting down and writing, with the face blank, and the screen or the notebook, for a long while at the start, blank too. Not only do they build metanarratives around their narratives; they cast themselves in the action, and in the lives of their characters. The sources of all great stories, they imply, are unrepeatable, unpredictable, and almost unbelievable.

The more common genesis of stories is much less exciting. Stories occur to their writers during bus rides, long drives, acts of listening and reading, moments of passivity. The ideas weren’t there, and then they were. You reach for the best-looking red pepper at the grocery store, or rise out of the halfway point between asleep and awake, or mistake a stranger across the street for a friend – then suddenly, it strikes. You look the same as you did a moment ago. You note it on your phone, or wait until you’re home. You sit down for an hour after work, or between classes. Sometimes the ideas are not there, but it is important to you that they arrive, so you milk the stone your brain is, milk-milk-milk, until there’s something. It’s labour, often boring to the worker, almost always boring-looking to the observer.

Writing is this spectacularly unglamourous act. Strangers rarely fly you to Iowa, sit you down at restaurants, or track you down from across the country to tell you fantastic, life-changing stories that they need you, in turn, to tell to the world. Waller might get it right when he says it “transformed the way I think” to write the story he made up; that part I believe. But writing doesn’t have to be based on real events to transform the way its writer thinks. Fiction might, in fact, be more conducive to such transformations than stories that have actually happened. But such transformations don’t take an external appearance. To point any cameras their way would be a silly use of acetate or data. Most often, the product will outshine and outlast the process that came before it.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Ben Ladouceur is a writer living in Ottawa. His first collection of poems, Otter (Coach House Books), was selected as a best book of 2015 by the National Post, nominated for a 2016 Lambda Literary Award, and awarded the 2016 Gerald Lampert Memorial Award for best debut poetry collection in Canada. Ben is the prose editor for Arc Poetry Magazine.