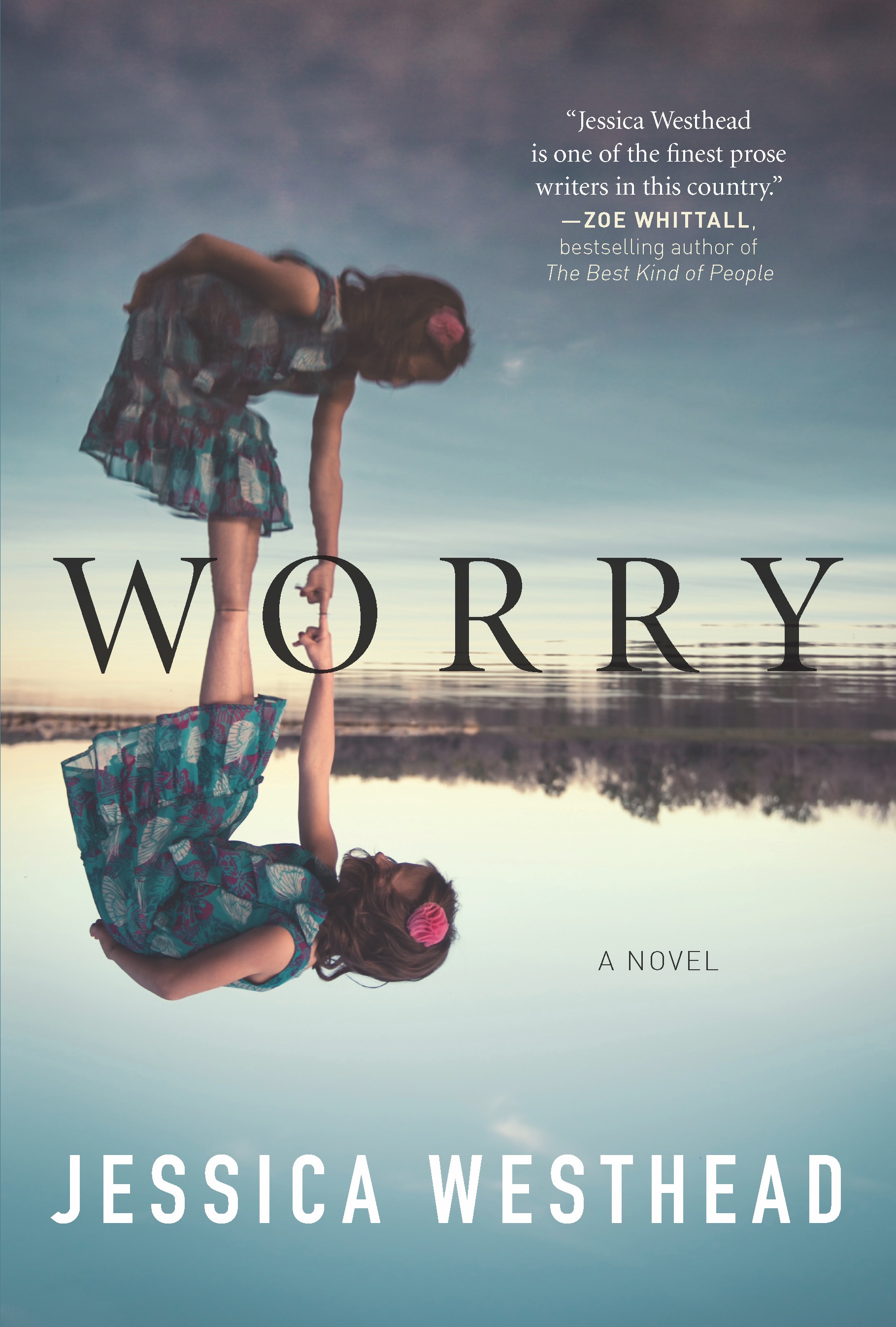

Book Therapy: Jessica Westhead’s Worry

By Stacey May Fowles

"Her brain and her body were still so wobbly then. Nothing about her was behaving the way it was supposed to. The birth had been a traumatic one, and she thought she would never heal.” - Jessica Westhead, Worry

In the months that followed the birth of my daughter, I found it impossible not to worry. I’m sure there’s a degree of postpartum concern that it is considered perfectly “normal” (whatever that means,) but mine seemed to buzz and crackle like an unexpected electrical storm, intent on clouding the sweetness of our first precious moments together.

My exhausted mind flashed with all sorts of dire scenarios in which she would come to harm, sabotaging the blissful glow of new motherhood that was promised to me by the Instagram posts of so many “momfluencers.” It seemed like there was something poisonous lurking inside my head, a voice that warned she might disappear, evaporate into the air, like she was something I had dreamed up that could be snatched away at any moment.

I have heard that this is a common affliction among mothers who have experienced infertility and pregnancy loss. We have spent so much of our time wanting and hoping, grieving the loss of a life we wanted so badly, that when it does arrive we can’t get comfortable with the reality of it. It makes perfect sense, really. It’s so hard to embrace and enjoy something you fear will be taken from you—that has been taken from you before.

When this is the reality of so many mothers (infertility effects about 1 in 6 couples, and somewhere between 10 and 15 percent of known pregnancies end in miscarriage,) you would think we wouldn’t mock and deride motherly worry the way we do. We wouldn’t punish or pathologize it, and we certainly wouldn’t be so callous as to label a worried mother a “problem.”

Maybe it’s because infertility and pregnancy loss have been pushed into very private places of suffering, but when a new mother reveals her perfectly natural and perhaps—given her experience of loss—inevitable worry, she is at best lightly mocked and at worst told she is doing real harm. (I can’t even tell you how many times I have been sternly warned by parenting manuals and experts that my anxiety will rub off on my infant, now toddler.)

I recently confided in another mother about those early, frantic, looping worries, about the places my mind went when I didn’t want it to. As someone who had experienced pregnancy loss, she understood where it came from, and offered comfort in the form of commiseration.

“It’s like ‘oh what’s the worst that could happen?’ and then the worst—at least in terms of pregnancy—does happen and you’re like ‘oh shit, well now everything is fair game.’”

***

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

Ruth is the perpetually unsettled protagonist of Jessica Westhead’s recent novel, Worry. Mother to four-year-old Fern, it would be easy to assume she’s that stereotypical pestering mother on the playground we so love to mock—constantly hovering, constantly furrowed brow, constantly wondering about some unseen danger that may befall her precious daughter. The kind of mother who catalogues choking hazards and toxins, who carries a bag full of items that will prepare her for any potential disaster, big or small. As we strive to be carefree and easy-going moms, we love to make fun of her and are also terrified that we will become her.

But this book does much more than merely deliver on preconceived notions. It works harder, offers more complexity and nuance, and belies the predictable. “Worry is a thoughtful and multilayered book that explores the many factors—both personal and societal—that might cause a parent to retreat into a place of worry,” writes parenting expert and author of Happy Parents, Happy Kids, Ann M Douglas. “At the start of the novel, we sense that something is wrong, but it takes us a long time to figure out what that ‘something’ is.”

Sometimes I wonder what terrible thing must befall a woman—a mother—to make her worry in those early days justified? How bad must it be for our culture to deem her level of concern and fear an understandable part of her experience, instead of just a detestable character trait?

When will we offer her reassurance, resources, help, and healing instead of warnings, derision, and judgment?

I was twelve years old when the American psychological thriller The Hand That Rocks the Cradle was released. Hugely popular at the time, the movie tells the story of “good mother” Claire Bartel and a psychopathic, vengeful nanny named “Peyton” that finds her way into her home. Unbeknownst to Claire, Peyton blames her for the loss of her own baby and subsequent hysterectomy, and endeavours to systemically destroy Claire’s picture perfect happy life by turning her entire family against her—new baby included.

When I initially watched the movie, I admit I was entertained. I never questioned this grotesque—and frankly lazy—idea of “infertile, childless woman as villain.” Culturally, the woman who cannot (or doesn’t want to) have children is commonly viewed as broken in some fundamental way. It’s not much of a pop culture leap to have her vengefully breastfeeding the good mother’s child, seducing the good mother’s husband, murdering the good mother’s best friend, or covertly emptying all of the good mother’s asthma inhalers.

The Hand That Rocks the Cradle is of course an extreme and yes, laughable example, but after years of dealing with infertility and loss, it’s hard not to view Peyton and her pathological nature as a cautionary tale. If your journey to motherhood fails, if it is unsuccessful, you too will become the bad guy in the good mother narrative. Your bitterness, your resentment, your jealousy over pregnant bellies on the subway and in the grocery store will make you a shell of your former, hopeful self. You will single-mindedly hate other people’s happiness. You will never find peace. (None of these things are true, of course. But we are certainly made to fear them, adding even more worry to the growing pile.)

In Worry, Jessica Westhead doesn’t rely on tired stereotypes of infertile women or “failed” pregnancies to create a taught, tense, and compelling narrative. Ruth, with the unimaginable suffering she has stoically endured, is not transformed into some convenient bitter baby-stealing, life-ruining, vengeful mom-villain to serve the story (and our fear or mockery.) Instead, Westhead treats Ruth—her trauma and her worry—with thoughtful accuracy and kindness. Instead, Ruth is the novel’s hero.

It’s precisely what makes Worry a revelation.

***

Perhaps out of that very fear that my worry will cause harm, I have been reading a great deal about the sources and ramifications of parental anxiety. What I have learned is that worry is indeed normal, and common, and can even be helpful. A fear of peril can and often does keep us and others safe, sometimes without us even realizing it. What is damaging is when it goes unquestioned and unchecked, when it turns to catastrophic thinking, when your worry bosses you around to the point you can not enjoy life. In some ways, excessive worry is less a flaw and more a necessary tool wielded incorrectly—a product of what you have experienced.

In a recent New York Times piece titled The Lasting Trauma of Infertility, Regina Townsend, founder of The Broken Brown Egg, writes, “Because it can be hard to fully grasp what infertility involves unless you’ve dealt with it personally, many people believe that it’s all about the end game, a baby—that if you could just get to that prize, the pain of infertility would fade away. But infertility is bigger than babies.” (She also goes on to add that research has shown women dealing with infertility have depression and anxiety levels similar to those with cancer, H.I.V. and heart disease.)

“You become used to living in a constant state of fluctuating despair and hope,” Townshead continues. “And this doesn’t turn off when and if you get pregnant. It doesn’t turn off when you hear or see the heartbeat. My son is 3. I’m still trying to turn it off.”

Jessica Westhead’s Ruth is trying to turn it off. There are so many of us trying to turn it off.

I rarely wrote about infertility while it was happening to me. The wound felt far too open, far too raw to share with anyone else, and even now that my daughter is about to turn two, in some ways it still does. But I did seek out authentic stories, hungered for the words of other women who had endured what I was enduring and fought their way through, women who were still fighting and simply living. Something beyond all the judgment and spiteful nanny caricatures. Something that treated the issue with the sensitivity and kindness it necessitated.

Something like Worry.

Book Therapy is a monthly column about how books have the capacity to help, heal, and change our lives for the better.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Stacey May Fowles is an award-winning journalist, novelist, and essayist whose bylines include The Globe and Mail, The National Post, BuzzFeed, Elle, Toronto Life, The Walrus, Vice, Hazlitt, Quill and Quire, and others. She is the author of the bestselling non-fiction collection Baseball Life Advice (McClelland and Stewart), and the co-editor of the recent anthology Whatever Gets You Through (Greystone).