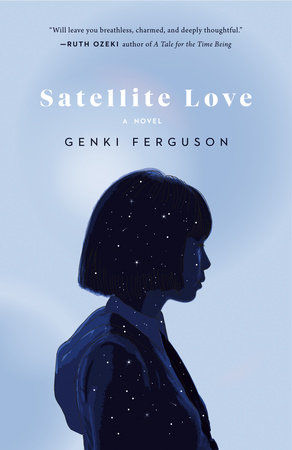

Book Therapy: Satellite Love

By Stacey May Fowles

“I think my favourite thing about humans was how they couldn’t fathom the thought of being alone.”

—Genki Ferguson, Satellite Love

My birthday is in April and I’ll admit I’ve never been very good at celebrating it.

I usually spend weeks pretending the day in question is not important to me, telling no one, planning nothing, and claiming I don’t really care. As a person who is not and has never been on Facebook (I know,) my friends don’t get that convenient reminder, meaning other than those who are skilled at remembering dates or good at writing them down, it’s generally up to me to cultivate any general well-wishing.

“Why bother,” I think. “It’s no big deal anyway.”

But then, when the day finally rolls around, I tend to feel a bit morose about both aging and loneliness. I’ll find myself feeling disappointed, even though I spent weeks claiming I didn’t care at all. And yes, I know it’s a self-defeating, childish habit—last year I even vowed to break it. 2020 was going to be the birthday I actually acknowledged, and invited other people to celebrate along with me.

I wasn’t planning anything major—just a couple of my very closest friends together at a favourite dive bar for a casual lunch. There was supposed to be greasy food and a bucket of mimosas. I even bought a dress for the occasion (and I never buy dresses.)

But as we all now know, that simple plan didn’t even remotely come to fruition. Instead I spent my 2020 birthday at home in lockdown, far more than six feet away from my friends, eating a cake made from a box. I never actually wore the dress I bought, and that beloved dive bar is now closed forever, a pandemic casualty like so many others.

I certainly don’t expect any pity for this story—by now everyone has had their own pandemic birthday and has yearned to celebrate milestones with the people they love and miss. As far as pandemic disappointments go, my box of chocolate fudge cake rates pretty low. But as my second birthday in lockdown rolled around, and I yet again didn’t bother to make any plans to celebrate it, I was struck by one major, soul-crushing thought.

Oh my god, I miss people so much.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

***

“It was during my third revolution around the Earth that I developed this creeping suspicion that I may not actually exist.”

This question of existence is how we are introduced to the “mind” of LEO, a Low-Earth Orbit satellite and the titular character in Genki Ferguson’s beautiful debut novel, Satellite Love. “Made of metal instead of flesh,” LEO drifts through the night sky, ultimately attracting the attention and love of sixteen-year-old social outcast, Anna Obata. From there the two form a unique bond, one that defies easy characterization and is rooted in an exploration of what it means to be human.

Anna is the weird, wonderful and ultimately tragic driving force of Satellite Love, struggling with the periodic absence of her mother, the deterioration of her grandfather, and the vicious exclusion of her peers. Bullied mercilessly and mostly fending for herself, she asks, “how much will Anna put up with today?”

A rich and imaginative inner life is Anna’s primary coping mechanism, her ability to both seek out unconventional companions—real and otherwise—a method of staying afloat. In the face of so much rejection, she somehow remains stoic, finding a great deal of comfort in her own obsessions, and in the stars above. In very real love with her satellite, Anna asks, “Do you see this? Do you see what they’re doing to me down here?”

Mostly prompted by a blow described as “63% dejection and 37% confusion,” Anna finally summons LEO from the sky to keep her company. Now earthbound, her satellite/boyfriend spends a great deal of time trying to understand not only who or why he is, but existence itself.

“You’re imaginary,” Anna tells LEO in the first moments they are finally together. “A coping mechanism used to deal with intense isolation. I made you up."

***

When I say that I miss people, I don’t just mean those few pivotal birthday guests who were going to clink Champagne flutes with me in April 2020. I don’t just mean the people I call or text frequently when I’m sad, or mad, or simply bored. I don’t just mean my parents, or the relatives I’d have to travel long distances to see when the mere idea of traveling seems impossible to fathom.

When I say I miss people, I also mean the ones who I’ve only really been able to access at best via social media updates and at worst via fuzzy memory. I mean those admired acquaintances and “sort of friends” I’d run into at book launches and parties, while grabbing a coffee or on sidewalks when out for a stroll. I mean the kind folks who filled up and brightened the corners of my life—even if they weren’t exactly central.

One of the many pandemic lessons I’ve learned is that the people on the periphery are much more important to our well-being than we ever actually realized. They validate our world, our experience, and maybe even our existence, in ways that we perhaps failed to appreciate before. Being seen—really seen—by others is part of what keeps us going, what makes us who we are, and what makes us feel alive.

“Does the pandemic ever make you feel like you are disappearing?” I ask my friends. So many of them answer yes without even hesitating.

***

My second pandemic birthday has now come and gone, half-heartedly celebrated as Ontario schools closed again and another stay at home order was enacted. “It’s no big deal anyway,” I still found myself saying about the day, even though I now know that’s not entirely true.

What did make this year different from the last is that the end to isolation finally feels like it’s coming. Even as I celebrated without those I miss so very much, I could see the real possibilities ahead—future moments shared, enthusiastic toasts raised, the people I love and like finally embraced.

I do have to wonder, when things become “normal” again, how we’ll manage to reacclimatize ourselves to what was once ours. I wonder how we’ll successfully reintroduce ourselves to what we’ve lost, how we’ll reform our connections after our ability to keep in touch has all but dissolved. In some ways we’re all outsiders right now, looking in on our former lives, feeling the sting of exclusion from what once brought us comfort, and hoping it will soon return to us.

“The end was coming,” LEO tells us. “The only problem was, I didn’t know what that meant.”

Inevitably, Satellite Love’s Anna gets an answer to how much she can put up with, reaching her breaking point and making LEO’s philosophical musings all the more pressing. As any reader can anticipate—perhaps now more than ever—acute loneliness has the potential for serious outcomes, a painful fact Satellite Love handles beautifully.

Maybe an unconventional novel about the perils of loneliness is the perfect read for these unconventional, lonely times. Maybe we need the detached musings of a satellite in love, looking outside in, to remind us of what it means to be human—especially when our sense of self seems to be slipping from our grasp.

Oh my god, we miss people. But for now we must curl into our loneliness, and find our solace in the stars.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Stacey May Fowles is an award-winning journalist, novelist, and essayist whose bylines include The Globe and Mail, The National Post, BuzzFeed, Elle, Toronto Life, The Walrus, Vice, Hazlitt, Quill and Quire, and others. She is the author of the bestselling non-fiction collection Baseball Life Advice (McClelland and Stewart), and the co-editor of the recent anthology Whatever Gets You Through (Greystone).