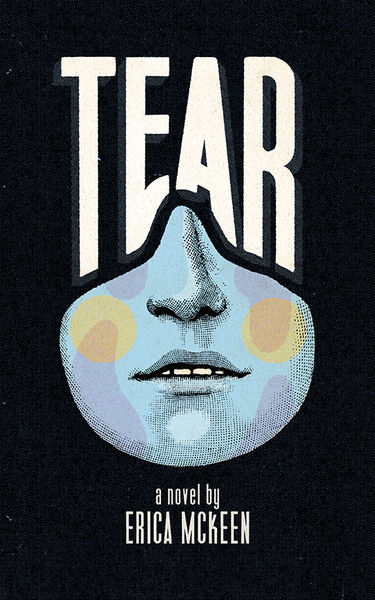

Book Therapy: Tear

By Stacey May Fowles

“The room was dark around her. She heard a sound of shuffling, of shifting, as of limbs being rearranged. Or maybe it was the sound of leaves shuffling, shifting at the tops of trees. Hadn’t she just been walking?

Was she sleeping? Has she been dreaming?

Was this dreaming?”

—Tear, Erica McKeen

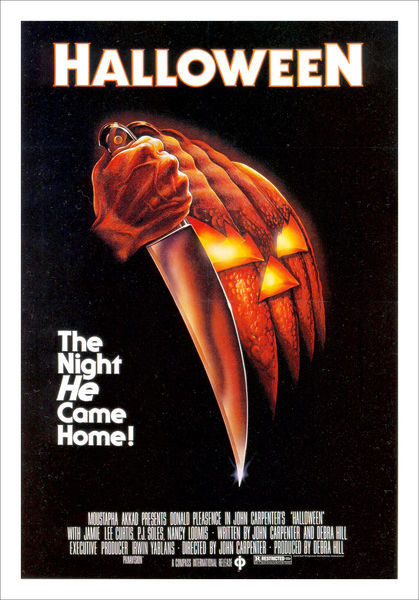

Every October, without fail, I watch John Carpenter and Debra Hill’s 1978 horror masterpiece, Halloween. Starring a young Jamie Lee Curtis as plucky final girl Laurie Strode, this low budget slasher flick has fascinated me ever since I was a less than enthusiastic undergrad assigned it in a seventies film class. Never one for jump scares or gore, I assumed I’d watch the mandatory screening with eyes mostly covered, but instead was enthralled as bad guy Michael Myers carved his way through Haddonfield, Illinois.

The movie’s simplistic premise—knife wielding madman lacking any personality terrorizes suburban babysitter—does so much work beyond any assumed shallow, shock value entertainment, and my now annual screening is an effort to get to the bottom of why exactly I love it so much. There are of course mountains of academic writing on the subject of this big screen scare, with writers far smarter than I expounding on the politics of the era, the phallic nature of the blade, the theory of the desexualized heroine and her uncanny ability to thwart vile virile monstrosity with little more than a coat hanger and a knitting needle. But I am more interested in personal motivations, why it seems that in times of hardship we turn to the fictional unspeakable for reprieve. (I’m so obsessed with the why of horror that this is not the first time I’ve written about it, and not even the first time I’ve written about it here.)

This year to expand my research I’ve decided to watch every film in the Halloween franchise—that’s soon to be thirteen movies, many of admittedly questionable quality, two directed by Rob Zombie, one starring Busta Rhymes, and another LL Cool J. More recent incarnations have offered particularly interesting takes on trauma and recovery, not to mention the glorious return of everyone’s favourite final girl, over forty years later. I am squeamish and easily spooked by the boogey man, so my hope is to figure out what exactly draws me to the masked, knife-wielding monster that stalks spaces we otherwise feel safe in.

Escapism, perspective making, and general release are answers I’ve explored, but there is a new horror-as-therapy theory I have been turning over in my mind. In the Halloween franchise death is vicious, loud, and cartoonish, and life generally frivolous. People are killed in particularly grotesque and often absurd ways, the loss rarely revisited as the plot bounds on. Sure there are dramatic monologues about relentless evil but rarely any actual mourning—no talk of grief, no methods of coping or discussions about meaning, only a ridiculous over-the-top blood bath with the aim of making the sensitive scream.

In the world of Halloween, people die, and everyone and everything just keeps on running. Life doesn’t matter, which is perhaps the film’s paradoxical reprieve. Because elsewhere life definitely matters so very much—excruciatingly so.

In Erica McKeen’s debut novel, Tear, university student Frances lives in the basement of a shared house in London, Ontario. Quiet and unassuming, it becomes easy for her roommates to forget she’s even there, going about their daily lives while she isolates herself beneath them in the bowels of their temporary home. That feeling of being disregarded eventually evolves into a kind of madness, as Frances succumbs to the suffocating darkness of her very separate space—“dark-dark like that blinding, black quality of your childhood nightmares.”

What unfolds then is an expertly written, feverish questioning of reality. Was there always a lock on the basement door? When was the last time Frances slept, ate, or saw another human being? Is this a memory or a dream? And most importantly, what is that relentless tapping on the wall?

“This feeling, however, would never leave, not for one second, one breath—this idea that something was living there with her. That she was not alone,” McKeen writes. “The thought traced its cold fingers on the underside of her skull, trickled down her spine, found its way into her shoulders and hands, her thighs and kneecaps and toes.”

The monster in Tear seems imagined until it is very real, clawing its way into the world via the literal and figurative entryway Frances herself has created. And while McKeen is an expert in conjuring the grotesque, she also excels in depicting the horror of being ignored and overlooked, of being forgotten, of feeling like you don’t matter or even exist—until you don’t.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

“What do you do when you hear scratching in the wall and there’s nothing but earth beside it? Really, what do you do? You tell someone and you get them to come and listen, and if they hear what you hear, you know it’s real…But what if there’s no one to tell?”

This is a different kind of terror than that escaped madman hovering ominously outside the window. Instead Tear is a deeply claustrophobic novel, concerned with what is real and what is imagined, and how being confined between the two is genuine torture. It is about the fears that come from within and the monsters we manifest as a result, forces that eventually destroy us—become us—without anyone even noticing.

“Francis thought of screaming, but she had screamed before and no one had heard,” writes McKeen. “She had banged before, bellowed and scratched before, and no one had heard. For years no one had heard her. From the beginning of everything, from the starting point of her very self, no one had heard.”

This October, my Halloween-related conclusion is that the discomfort of the Michael Myers universe is actually pretty comfortable. That’s not to take away from the film’s depth—I am certainly one of its most ardent supporters—but for a movie with so much carnage it doesn’t concern itself all that much with the actual ramifications of death. In many ways, the movie is a straightforward escape from loss by means of how gratuitously it serves it up.

Tear on the other hand belongs to a category of horror preoccupied with how unreliable our perception of reality can be. It suggests the kind of violence we can enact on each other without ever pulling the carving knife from the block. It offers up the truly destructive forces of human emotion and human neglect, and gives us a loss that matters—excruciatingly so.

“She had thought, consciously or not, monster.”

Book Therapy is a monthly column about how books have the capacity to help, heal, and change our lives for the better.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Stacey May Fowles is an award-winning journalist, novelist, and essayist whose bylines include The Globe and Mail, The National Post, BuzzFeed, Elle, Toronto Life, The Walrus, Vice, Hazlitt, Quill and Quire, and others. She is the author of the bestselling non-fiction collection Baseball Life Advice (McClelland and Stewart), and the co-editor of the recent anthology Whatever Gets You Through (Greystone).