Book Therapy: The books that helped us through 2020

By Stacey May Fowles

“I wanted to start making things that made me and others feel hopeful—even when it felt like there isn’t much to hold onto, and even when we just didn’t feel good.”

—Hana Shafi, Small, Broke, and Kind of Dirty

When our pandemic reality arrived in Ontario in the middle of March, a lot of people told me they were having a hard time reading. Even the most dedicated book lovers I knew could barely get through a few pages without being distracted by the anxious buzz of bad news. Books languished on shelves and nightstands while many of us were glued to ominous daily press conferences, only really able to tolerate reruns of our favourite episodic television, and trying our best to get through.

Thankfully, reading returned to us eventually. For me, that pleasure arrived by way of countless pulpy thrillers that didn’t ask too much of my attention span, and then with non-fiction works that encouraged me to step back, unplug, and take stock. By late summer I was in a hammock luxuriating in the luscious escape of Marlowe Granados’ Happy Hour (Flying Books,) delighting in the effervescent exploits of her wry party girls. The early fall found me on a blanket in the park with the generous, fierce wisdom of Hana Shafi’s Small, Broke, and Kind of Dirty (Book*hug Press,) while winter’s approaching chill saw me snuggled up with the vulnerable, earnest honesty of Marlee Grace’s Getting to Centre (HarperCollins.)

If cultivating gratitude really is a way to survive the worst, I’d definitely put books on my 2020 shortlist of things to be thankful for.

During an exceptionally difficult year, this column has attempted to celebrate the comfort, healing, and help books that can bring, even in our darkest moments. For the last instalment of 2020, it felt fitting to ask a number of writers and publishing professionals what books helped them the most during these challenging times.

Here’s what they said...

Kerry Clare, author of Waiting for a Star to Fall (Doubleday Canada):

My vote is for the memoir The Bite of the Apple, by Lennie Goodings (Biblioasis.) In a moment of extreme division and polarization, this memoir is a balm. Goodings writes about taking inspiration from Virago author Grace Paley, who called herself “a somewhat combative pacifist and cooperative anarchist.” Goodings continues, “Somewhere between these two options—fuck the patriarchy or keep plugging away for what you know is right— is how most women find themselves responding to sexism and inequality. We need rage and inspiration, we need realism and practical solutions, and we need to know our histories, literary and otherwise.” There is also the part about how Decca Mitford and Maya Angelou were devoted friends and did a mean rendition of “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer”—WHAT?

Jen Sookfong Lee, author of Finding Home: The Journey of Immigrants and Refugees (Orca) and The Shadow List (Buckrider Books):

How Much Of These Hills Is Gold by C. Pam Zhang is a fantastical and wild retelling of gold rush-era North America, with two Chinese siblings—Lucy and Sam—wandering through the woods with the body of their dead father in a trunk. In 2020, when anti-Asian racism was rattling me to my core, it was deeply comforting and uplifting to read a novel that so fearlessly subverts the great Western mythology of pioneers and prospectors by centring a fierce Chinese family that grapples with otherness, gender, and the long shadow of grief, while still caring for and loving each other. We are not objects for someone else's racial hatred; rather, we can and we do make magnificent art, as How Much Of These Hills Is Gold exemplifies.

Steven W. Beattie, reviews editor, Quill and Quire:

As a teenager in the 1980s, my favourite literary genre was horror. As a bookish kid at an all-male high school that prized athletics as the apogee of masculinity, I frequently felt out of place; this was also the decade of Reagan-Thatcher, AIDS, and potential nuclear holocaust, so places of solace were few and far between. I found horror fiction – ghoulish, grotesque, and gory – to be a refuge from the quotidian terrors of everyday life. Fortunately, my adolescence coincided with the golden age of paperback horror publishing, an era lovingly chronicled in Grady Hendrix’s lavish 2017 compendium Paperbacks from Hell.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

Reading this book in 2020, and revisiting all those lurid covers from my youth, replete with skeletons and creepy kids and killer slugs, was nostalgic, to be sure, but also rekindled a love of the genre that had lain more or less dormant for many years. Going back to key titles from the era—Michael McDowell’s Southern Gothic ghost story The Elementals, the short fiction of Ramsey Campbell and Clive Barker, Bari Wood’s Jewish horror novel The Tribe, Elizabeth Angstrom’s twisted pseudo-vampire novel Black Ambrosia—led down a rabbit hole of new discoveries, including more contemporary genre writers I’ve newly encountered, people like Victor LaValle and Livia Llewellyn.

It has become a thudding cliché to point out that 2020 is a year like no other, overflowing with horrors on the medical, economic, racial, and political fronts. Horror fiction provides a unique metaphoric frame through which to view the fears and upheavals of the real world; in that sense, it is for me both edifying and a mechanism of escape. It’s provided me with moments of paradoxical comfort over the past year, and Hendrix’s book was the gateway.

andrea bennett, author of Like a Boy but Not a Boy (Arsenal Pulp Press):

I have generalized anxiety disorder, and this has been an awful year for it. While I could cite the mostly queer-authored books I did manage to read this year, if I'm honest, the book that really got me through was the audiobook version of John Grisham's only non-fiction book, The Innocent Man. The week of the US election, I really just completely lost my ability to fall asleep. My nerves were shot. And so I downloaded the Libby app on my phone and took The Innocent Man out from the library after a few clicks. My thanks to narrator Craig Wasson: I was finally, finally able to get some rest listening to his calm, warm reading voice.

Damian Rogers, author of An Alphabet for Joanna (Knopf Canada):

Strangely, the book I can't stop thinking about right now is one that I bought in 2003 and just got around to reading this fall: Pattern Recognition by William Gibson. Set in the year after 9/11, its atmosphere of paranoia and global instability, and its engagement with the slipperiness of what we call history, or time, or power, helped me see the present moment in an enlarged context. It reminded me that these sensations of disorientation and dissonance, the inevitable numbness in the face of relentless shock and awe, is part of a larger, looping pattern of human activity, and that the past can feel as mutable as the future.

I was also deeply moved by the digital libretto to Daniela Gesundheit's Alphabet of Wrongdoing album, which included a long thoughtful essay rethinking the roles of forgiveness and atonement in traditional Jewish ceremony, as well as powerful meditations on the links between personal responsibility and community. It's a beautiful project.

Shannon Webb-Campbell, author of I Am a Body of Land (Book*hug Press):

Mi’kmaq poet Shalan Joudry’s Walking Ground (Gaspereau Press) is a collection of poetry that grounds the reader in ecological time. Her sure-footed, even keeled heart, and nurturing poetic voice takes you to the woods, instructs you to take off your boots, and walk barefoot on the earth. To connect with what matters most.

Walking Ground is filled with gentle wisdom, Mi’kmaw language, and offers generous reprieve, and the potential of rebirth after a profoundly difficult year. Personally, reading Joudry’s poetics reconnected me to the land, to our shared languages, and the ongoing challenges Indigenous Peoples continue to face due to the legacy of colonialism.

In the poem, “Qalipu Migration” (the Mi’kmaw word for caribou), Joudry cites the footnotes as a “new Mi’kmaw community/band in Newfoundland,” which made me stand up a little taller as Joudry addresses my community Qalipu Mi’kmaq First Nation. This was the first time I’ve read another Mi’kmaq poet who doesn’t have specific ties to Ktaqmkuk/Newfoundland write about the complex issues around Qalipu Mi’kmaq First Nation.

Joudry writes, “summoning each other out/ rounding up the heard/ and your children’s children/ for the long home-bound trek.” As a Mi’kmaq poet whose membership in the Qalipu Mi’kmaq First Nation was granted and then revoked, colonialism continues to fracture the identity of the Qalipu Mi’kmaq peoples and perpetuate trauma, creating a sense of estrangement or unbelonging through government-dictated criteria and selection processes for band members.

Jourdry assures readers like me in the final stanza, “qalipika’tiek/ searching our past/ for land you belonged to/ feet thundering home.” And even though my story is complicated by the fact that the Mi’kmaq Grand Council, the traditional government of the Mi’kmaq people across Canada, has also refused to recognize the legitimacy of the Qalipu Mi’kmaq First Nation Band and its members, a fellow Mi’kmaq poet does.

Walking Ground carries forward the resilience of Mi’kmaq culture and is a collective call for the work we all need to do for healing and reconciliation to occur.

After all, we all need help gathering, collecting and healing in order to make the long walk home.

Farzana Doctor, author of Seven (Dundurn):

Early in the pandemic, I read Vivek Shraya's The Subtweet. It's a nuanced and cheeky exploration of women's friendships, social media, and the trials and rewards of being an artist. In the midst of all the world's chaos and anxiety, I appreciated the distraction of a relatable, smart and fast-moving read. I was also preparing for Seven's release, so I followed Vivek as she promoted her online events like a pro, and picked up a few ideas and strategies.

Kate Hilton, author of Better Luck Next Time (HarperCollins):

At the heart of Ariel Levy’s The Rules Do Not Apply is a truly horrendous, life-altering experience: a late-stage miscarriage, endured alone, on a journalistic assignment in Mongolia (the original New Yorker piece, “Thanksgiving in Mongolia" is also a stand-out). Why read such a book in 2020? Because the writing is exceptionally honest, beautiful, and even darkly funny; because it’s about the hard work of resilience and the necessity of hope; and because it acknowledges the terrifying reality that we don’t control everything (or even anything), however talented and exceptional we may be.

“Until recently,” writes Levy, “I lived in a world where lost things could always be replaced. But it has been made overwhelmingly clear to me now that anything you think is yours by right can vanish, and what you can do about that is nothing at all.”

Andrea Warner, author of Buffy Sainte-Marie: The Authorized Biography (Greystone Books):

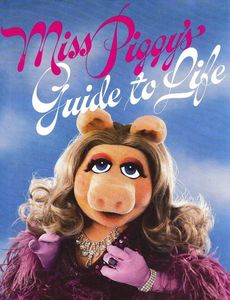

The book that I've turned to the most is Miss Piggy's Guide to Life. I'm supposed to be writing a book of essays about Miss Piggy but this year has often felt like a bunch of raw nerves agitating constantly between death and destruction and grief and fear. 2020 is a real MOOD, as my friend Cynara Geissler would say. But spending time with Miss Piggy's Guide to Life—a curious, kitschy, funny, and genuinely thought-provoking book—has brought me so much joy. Even if I just stare at the cover for 20 minutes and don't even crack the spine, it's like a kind of meditation. I know I'm always close to the writing, even if I can't be in it right now.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Stacey May Fowles is an award-winning journalist, novelist, and essayist whose bylines include The Globe and Mail, The National Post, BuzzFeed, Elle, Toronto Life, The Walrus, Vice, Hazlitt, Quill and Quire, and others. She is the author of the bestselling non-fiction collection Baseball Life Advice (McClelland and Stewart), and the co-editor of the recent anthology Whatever Gets You Through (Greystone).