Claiming Space for Indigenous Languages in English Literature

By Waubgeshig Rice

English is the language of the colonizer. It came with the arrival of settlers to what many people call Turtle Island, or North America. It is a relatively new language to this land, and has only been uttered here for a mere few centuries. But today, English is dominant, and rules discussions in virtually all social and professional areas. That includes, obviously, literature and media, which can be an uncomfortable paradox for Indigenous writers and storytellers.

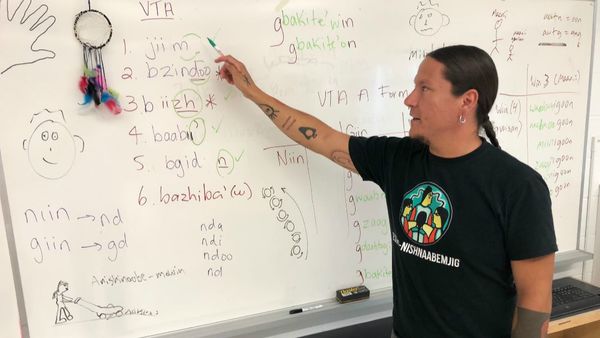

As an author and journalist, I make a living off the English language, while I barely know the fundamentals of Anishinaabemowin, the language of my people. I struggle with this reality daily, but I remain committed to including Anishinaabe words in all the literature I create. It’s a small but important act of reclamation and representation, and it continues to evolve with each book I write.

My relationship with the English language is complicated, but not entirely contrary. That’s because it’s also my heritage. I’m of mixed Anishinaabe and Canadian descent. My father is from Wasauksing First Nation on Georgian Bay, and my mother is from the nearby town of Parry Sound, Ontario. Her roots go back several generations to the United Kingdom, and as such, English is part of my lineage.

Still, it’s the culturally dominant half of my background, and acknowledging its influence on me and my work does not excuse the brutal ravages of colonialism on the language and culture of my other half. That’s where my work to infuse Anishinaabemowin into English texts begins.

I have a very basic knowledge of my Indigenous language. I grew up hearing it spoken among elders and family members, and I learned some basics while attending elementary school in my home First Nation, but I never picked it up fluently. I’m working now to bolster my Anishinaabemowin skills, and it’ll be a challenging priority for the rest of my life.

But throughout my fiction career, the little bit I did know emerged in the stories I wrote. At first it was as simple as using words like “aanii” (hello) and “miigwech” (thanks) in place of English wherever I could. That was a conscious effort to remind people that the language is still alive, and to provide some comforting familiarity to Anishinaabe readers.

The more proper grammar I learned, the more I wanted to use it. But I was well aware of some of the problems around including other languages in English texts. The tendency throughout the history of publishing has long been to italicize anything “foreign”, distinctly placing another language as subordinate or alien next to English. Editors may also push back against including Indigenous words or phrases, so not to estrange mainstream white readers from a book. There are many obstacles to maneuver when taking this storytelling approach.

Thankfully, using Anishinaabemowin in my first two books was not a major issue. My short story collection, Midnight Sweatlodge, and my first novel, Legacy, were both published by Theytus Books, the longest-running Indigenous publishing house in Canada. The editors and publisher I worked with encouraged my use of language, and were proud to have authentically Anishinaabe voices and words thrive in the books they published. It was very empowering as an emerging author to experience this inclusive and auspicious approach to writing.

To my delight and relief, that approach was further nurtured through the editing process of my second and most recent novel, Moon of the Crusted Snow, which was published by ECW Press. Like my earlier works, it’s written almost entirely in English with Anishinaabemowin words and dialogue peppered throughout. And those language elements remained largely intact, even though I was no longer with an Indigenous publisher and editor. In fact, my editor, Susan Renouf, urged me to take my Indigenous language a step further in writing.

The original draft of Moon of the Crusted Snow included English translations of the Anishinaabemowin spoken by characters in the dialogue itself. So, for example, if a character said something like “aaniish ezhichgeyin?” they’d repeat “what are you doing?” right after. Susan encouraged me to remove many of those secondary translating statements, and write around the dialogue so a non-Anishinaabe reader would be able to understand what was happening. She said something like “let the reader figure it out for themselves.” It was a simple change, but it very much altered my entire mindset on using Indigenous languages in English literature.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

So now, as I write my next novel, I’m equipped with improved knowledge of Anishinaabemowin grammar, so much so that I’m comfortable writing longer chunks of dialogue in the language. How that ends up reflected in the actual published book depends on the editing process, but I feel confident and enfranchised to uphold the spirit of the language itself in a literary way. It’s a small step, but I feel it’s an important one towards proper Indigenous representation in mainstream arts and culture. We can resist ongoing colonialism and rightfully claim our places in these domains, one Indigenous word at a time.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Waubgeshig Rice is an author and journalist from Wasauksing First Nation on Georgian Bay. He has written three fiction titles, and his short stories and essays have been published in numerous anthologies. His most recent novel, Moon of the Crusted Snow, was published in 2018 and became a national bestseller. He graduated from Ryerson University’s journalism program in 2002, and spent the bulk of his journalism career at CBC, most recently as host of Up North, the afternoon radio program for northern Ontario. He lives in Sudbury, Ontario with his wife and two sons.