Considering the Incomplete

By Ben Ladouceur

I love to buy something then cut it in half. I did this recently with a product called the World’s Best Dishcloth and felt like a genius. Now I had two dishcloths and they were both the best dishcloth in the world. I once knew a man who did this with his books. He found his copy of Middlemarch too cumbersome for the bus. Being a hobbyist bookmaker, he split his Middlemarch into two parts, the first of which ended mid-sentence, the last of which began mid-sentence. On his bus rides to work and back, he read the first half, then the last, carrying the whole time half as much of Middlemarch as he would have.

His creation, two books from one, made me curious about the fate of these halves. Someday my friend would give these books away, or sell them, or die and thus prompt others to do away with the books somehow. What if these two books, to which he gave blank covers, got separated in the future? What if someone came across the first one and began to read from it, not realizing that, although the book would finish, the story wouldn’t?

I always feel similar concerns about multi-volume editions of large books, like Haruki Murakami’s IQ84, or Minae Mizumura’s A True Novel, or Roberto Bolaño’s 2666. If a book is split in two, or three, or seven, what a shame that its future reader might only have access to a fragment of its story. Such a reader can ultimately look forward to confusion and frustration, if also occasional awe at the standalone strengths of the writing.

Trying to imagine how it might feel to read such a work, however, I think of works that are published in an incomplete state, their lives and their authors’ lives cut short in the same moment. These works have the same potential for beauty as their finished counterparts, and such a condition can in fact elevate their power or grace.

In the Darren Aronofsky movie The Fountain, a sick woman asks her husband to finish writing her novel, which is one chapter short of completion. Then she dies. To me, this is a great gesture of love and trust. By asking this of her husband, she tells him that she is okay with his ideas, his handwriting, his voice taking space that would be hers, but for the grace of her terminal illness. The husband doesn’t touch the book, instead pursuing his research on immortality, hoping to bring her back, and to make her live forever, in flesh instead of letters. It doesn’t go fantastically for him. It turns out humans always die.

As a result of this, some books will of course never be finished. Bolaño, for instance, died before he finished 2666. There were revisions still to be made. We will never know how the book would have read, had he been provided with all the time that he would have liked to have. But I remember discussing 2666 with a friend who argued that the book’s success is contingent on its incompleteness. 2666 is a sprawling book, full of police officers and prostitutes, European academics and Mexican factory workers, hundreds of acts of violence and pages-long accounts of half-forgotten dreams. There are so many characters and settings, at times only tangentially connected. A book like this cannot function in a complete form. Its borderless exploration of countless themes is key to its success. A final draft would be a sort of domestication, and this book is best off wild. (It’s also the case that Bolaño intended for 2666 to be published bit by bit over the course of years, but following his death, his executors allegedly ignored this wish. As such, perhaps a chance encounter with a chunk of the book, rather than the whole thing, would be more in line with the author’s intentions for his reader.)

In the late 90’s, PK Page and Phillip Stratford were writing a collaborative poem called a renga together via snail mail. It began when Page learned that Stratford, an old friend of hers on the other side of the country, had been struck ill. The poem, along with their charming and minutiae-laden correspondence, was published in the book “And Once More Saw the Stars: Four Poems for Two Voices.”

Stratford died before they finished the poem, which is divided into four sections: Wilderness, Garden, Sea and Stars. Stratford’s illness haunts the margins of the whole text. As Page writes in the introduction, “I now see that his demolition of the garden in the opening quatrain of sonnet IV clearly reflected the state of his health.” At one point, Stratford has an operation to remove his larynx, leaving such writings as this renga to become his only voice. (Page only learned about this operation later.)

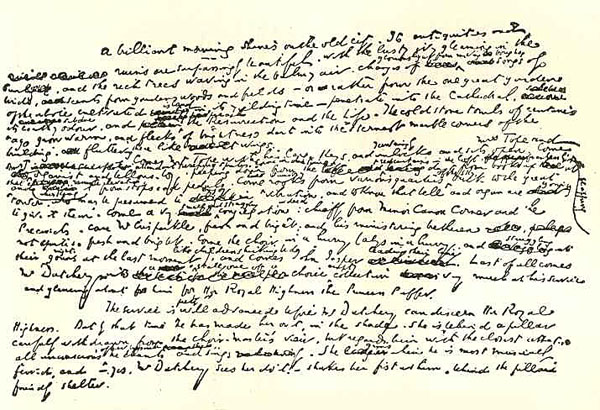

Stratford’s death took place partway through Space. Although it was her fellow author’s turn, Page wrote the last stanza herself:

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

A week before your death astronomers

reported planets circling a star

deep in the Milky Way – three, Jupiter-class –

the first true solar system outside ours.

Oh Philip, do you rage in space?

Do you?

In poetry, I think of line breaks as an extra layer of grammar, giving the poet an opportunity to end her sentences more than once, not just with a piece of end-punctuation, but also with white space. The line break is a middle that imitates an ending. Here, Page breaks the line before the meter is finished, indenting her final words in a way that emphasizes the fracture (such indents do not take place anywhere else in the rest of the poem). The incompleteness of the ending becomes the whole idea, bringing the poem’s tragic themes to the forefront.

Then the poem is over, and so is the book – not even a notes and acknowledgements section at the end. Stories, sentences and human lives don’t always end tidily, and some texts speak most clearly when imitating this dilemma, even incidentally. Reflecting on Page and Stratford’s poem, I figure than any fragment of any story might benefit a reader with the advent of its endlessness.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Ben Ladouceur is a writer living in Ottawa. His first collection of poems, Otter (Coach House Books), was selected as a best book of 2015 by the National Post, nominated for a 2016 Lambda Literary Award, and awarded the 2016 Gerald Lampert Memorial Award for best debut poetry collection in Canada. Ben is the prose editor for Arc Poetry Magazine.