(Cook)Book Therapy: County Heirlooms and Pandemic Cooking

By Stacey May Fowles

“We hope you’ll try making some of these recipes, and we encourage you to find ways to make them your own. And we also hope this book inspires you, wherever you live, to find personal ways to connect with local growers, chefs, and makers—and of course, your food.”

—Leigh Nash, Publisher, Invisible Publishing

One Sunday evening, 128 days after my family’s pandemic isolation began, I made Natalie Wollenberg’s “puttanesca sauce with roasted eggplant.”

It’s a deeply satisfying and forgiving dish to make, beautifully simple but with a definite occasion feel. The ingredients suggest fun decadence but are not impossible to find—eggplant, anchovies, capers, shallots, Kalamata olives. I had been looking forward to putting it together for over a week.

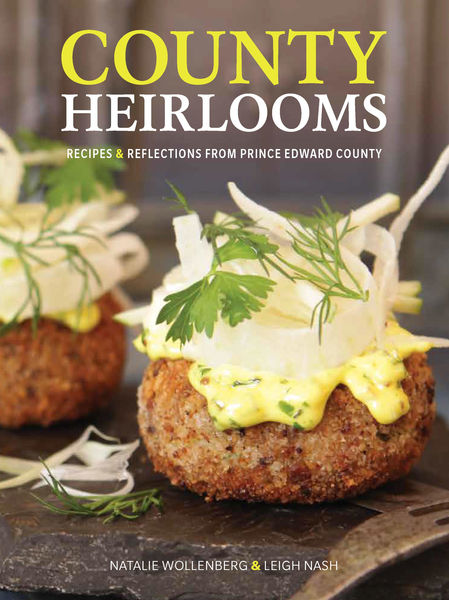

Natalie Wollenberg is the co-editor (along with Leigh Nash) and one of forty-two contributors to Invisible Publishing’s first foray into cookbooks, County Heirlooms: Recipes and Reflections from Prince Edward County. She also co-owns The County Canteen and 555 Brewing Company with her husband Drew, and chose the rich and flavourful sauce as her contribution because of its connection both to him and her passion for cooking.

“I love that people enjoy what I cook for them,” she says. “That’s why I’m sharing my recipe for puttanesca—it’s Drew’s favourite meal. And that’s why I love making it.”

Preheat oven to 425 F. In a large bowl, toss the eggplant with half the olive oil, and season with salt and pepper to taste.

***

The connection between food and pandemic isolation has become a bit of a cliche ever since those early sour dough starter days (mine totally failed, by the way.) People have been cooking, baking, tasting, sipping, and savouring their way through the need to stay home, embracing food as familiar comfort, site of celebration and creativity, and even as a way of wrestling back some much needed control.

The hard reality is that for a lot of us, the pandemic has made us feel like our dreams, both large and small, are dying. The plans we so carefully set, the things that defined us daily, have all but evaporated, and while we will recover some in time, others parts have drifted so far away we will struggle to salvage them at all.

I know so many parents—mostly mothers—who, in lieu of any reliable childcare, have had to opt out of their once busy and fulfilling careers. They’re filling a gap, without any real knowledge of how wide that gap is inevitably going to be. Others like myself are hanging on to what work we can while also attempting to parent full time, often berating ourselves because we’re failing at both. (We’re not, I keep telling myself.) We’re beyond exhausted and feel like we’re falling further and further behind, even as the province proclaims a victorious reopening.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

It may seem anecdotal that a handful of my mom friends and I had to make some hard choices, but the reality is that women's participation in the labour force is down to its lowest level in three decades. I’m certainly aware my work days have been truncated in favour of setting up elaborate craft projects and leading toddler music sessions, that I long to get back to that book I’m supposedly writing, that I’ve had to say no to opportunities that now preclude me because of my ever-present toddler. That I’m unsure and mostly terrified about how this will all effect us in the long term.

Add red pepper flakes, anchovies, tomatoes, red wine, olives, capers and oregano. Simmer for about 15 minutes or until the sauce thickens slightly.

And so, for whatever reason, I found solace in cooking an elaborate meal. When it felt like nothing could ever get done, I found the post-toddler bedtime satisfaction of actually finishing something on my own terms. When I felt like I was losing my sense of self in the moniker Mother, to a lack of choices, to an uncertain future, I chose to temporarily lose myself in the making of a meal.

***

Sometimes my daughter will stand on a step stool at the kitchen counter and pretend to cook.

I’ll provide her with any random ingredients we have on hand, things we can spare that will entertain her and allow her to make a good natured mess. She’ll carefully measure flour or shake baking soda into her favourite silver mixing bowl, proudly proclaiming she’s making pancakes, cookies, or cake. She’ll create mysterious—and yes, sometimes very disgusting—concoctions in that adorable way children do when they’re experimenting in the kitchen for the first time.

I admit this kind of “cooking” with her is sometimes nothing more than a bridge to a reprieve—a way for an exhausted working mother to drink a hot coffee, or to simply kill a forty-five minute block when time seems to stretch on forever. But it’s also an easy way to invite her into the household satisfaction that cooking can bring, to show her that food is more than just sustenance. It’s also connection, and joy, and love.

Since March there have been taco nights, and pizza nights, and a few ice cream for dinner nights. I have made a beloved friend’s favourite rhubarb crumble bars, Cacio e Pepe, Rice Krispie squares, and my mother’s famous cheese, onion, and potato pie. (I get a lot of recipe requests for that one.) I’ve assembled dozens of comforting canned soup casseroles, epic four hour velvety stews from scratch, and one rather adorable birthday cake for a stuffed animal named Bean.

Some dishes have been hilarious failures (the dumplings that fell apart, the bread that resembled an actual brick) while others have offered surprising success (cauliflower mint rice—who knew?) Some things I made for reasons of economy, or mastery, or affection—to see that wilted vegetable used up, to see a leftover put to good use, to see the people I love taken care of.

I made meals to make sure nothing was wasted in a time where things felt taken from us. I made meals to conjure gratitude, and pleasure, and plenty, when all three felt fleeting.

***

You could call Wollenberg’s humble Spaghetti alla Puttanesca a pretty standard dish, especially with some of the more adventurous forays into food that grace County Heirlooms’ full colour pages. The book is indeed beautiful to behold, offering up fantasy meals like Mousse de Foi, Woodfired Belgian Endive, Pickerel Cakes with Fancy Tartar Sauce and Fennel Slaw, and Sparkling Raspberry Gelée—each lovingly introduced by a Prince Edward County chef, farmer, or food producer.

And while Wollenberg’s recipe certainly does rely more on comforting faves like tomatoes, olive oil, olives, capers, and garlic, simmering slowly together in a pan, it is ultimately set apart by the addition of that eggplant; diced, tossed in olive oil, salt and peppered to taste, and roasted to divine sweetness on a baking sheet for twenty minutes. The eggplant is then added to the sauce in the final phases of said simmering, along with a healthy fistful of chopped parsley that, on the 128th day of pandemic isolation, I happened to cull from my garden. (Pandemic gardening is, of course, another notable cliche.)

Even though the kitchen has long been a site of enormous domestic labour inequality, and is often easily dismissed for myriad mostly gendered reasons, in times off loss and disarray it also has the potential to be a sphere that is deeply groundling and healing. Food is ultimately a way to express care and comfort, and the pandemic has brought out that impulse in many—a sachet of cumin shared by a neighbour, porch wine swaps facilitated by the expert down the street, a bag of frozen bolognese dropped off by a dear friend.

Serve pasta topped with puttanesca sauce, sprinkled with additional chopped parsley, liberal shavings of Parmesan, a healthy glass of wine, and baguette.

Thanks to the soothing, meditative, and methodical process of putting even the most mundane ingredients together, I found a temporary escape hatch from all that helplessness and anxious uncertainty. Cooking became a surprising way to assert my sense of self—I started to look forward to the time of day where I could make something real and beautiful and fulfilling on my own terms, where I could feel in control while everything else felt so completely out of control.

***

In 1942, author MFK Fisher released How to Cook a Wolf—a book I recalled from a long ago university food literature class and repurchased during those early pandemic days. Part cookbook, part essay collection, part font of wisdom, Fisher aimed to inspire courage and creativity in the kitchen during a time of intense anxiety, unfathomable uncertainty, and the reality of wartime food shortages.

“I believe that one of the most dignified ways we are capable of, to assert and then reassert our dignity in the face of poverty and war's fears and pains, is to nourish ourselves with all possible skill, delicacy, and ever increasing enjoyment,” she wrote. “And with our gastronomical growth will come, inevitably, knowledge and perception of a hundred other things, but mainly of ourselves. Then Fate, even tangled as it is with cold wars as well as hot, cannot harm us.”

Food is, of course, nourishing and life giving. I’ve also been to enough socially distanced neighbourhood park and Zoom dinners to know food brings us together even when we’re asked to be physically apart. By putting so much care into the preparation of a meal, by allowing food to lend structure and by making it the focal point of our days, eating has the potential to become even a temporary reprieve from the chaos and death that is everywhere.

The world may be falling apart, but you can pull together a simple and satisfying sauce for you pasta. You can break bread with the people you want to keep safe. You can leave a meal on the porch of a person you can’t share a table with. You can swap recipes, and drop off coveted ingredients, and make a loved one feel loved. You can share a feast with your community, and find the space for yourself when your sense of self feels stolen. Everything can feel wrong, but we can still conjure gratitude, pleasure, and plenty. We can still enjoy a meal.

Then Fate cannot harm us.

***

All royalties from sales of County Heirlooms will go to support Food to Share’s ongoing programming.

Book Therapy is a monthly column about how books have the capacity to help, heal, and change our lives for the better.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Stacey May Fowles is an award-winning journalist, novelist, and essayist whose bylines include The Globe and Mail, The National Post, BuzzFeed, Elle, Toronto Life, The Walrus, Vice, Hazlitt, Quill and Quire, and others. She is the author of the bestselling non-fiction collection Baseball Life Advice (McClelland and Stewart), and the co-editor of the recent anthology Whatever Gets You Through (Greystone).