Defending your writing

By Carrianne Leung

Ever since I can remember, I wanted to be a writer. As a kid, I read everything in my library from A – Z. I was the secretary of the Library Club and loved my after-school gig of sorting the books according to the Dewy Decimal system. Books were my world. No, they were better than my world; they extended far past it and lit my mind up like neon. And so, when I was a little grasshopper, I wanted to be part of this magic and be a writer. I know this sounds familiar to many of you. Isn’t this the story of many writers? Were you one of those kids sitting in the corner with noses pressed in a book, finding doors and windows too?

In school, I always received good feedback from teachers. They would hand me back my poems and stories and look at me differently, startled that silent Chinese girls like me could have such imagination and the command of language express to my technicolour brain. After high school, I kept writing, but mostly in private. I filled stacks of blank notebooks with a mix of journal writing and love poems. They were angry and sweet and hopeful and earnest.

For a long time after, I still kept the dream of “one day, I will be a writer,” but I realize now that perhaps I was always a writer. Maybe it began long before the first time I published. It began when I was a grade 4 kid crafting stories about a wandering and talking garbage can who longed to be something else, written in careful cursive on that blue lined paper with the red margins. I wish I had given myself that title then and not fussed about it so much through my adulthood about wanting so much to be a “writer.”

The truth is, I was terrified to take myself seriously. I didn’t have the audacity to claim the moniker “writer” because I thought what I wrote would be no good to anyone else. For a long time, I was satisfied to write for myself. When you are compelled by language and can only make meaning of things through writing about it, there is little choice but to write. You do it even if no one is reading. What is that thing about the tree falling in the forest with no one around to hear it? Of course, it’s a no brainer for me - it still made a sound.

One day, I read somewhere that you are only a writer if you have a reader. This thought stuck with me, and I turned it over in my head for a number of more years. While writing gave my life meaning, pleasure, relief, it was true that I also wanted to communicate. Like open my head and pour the contents into someone else’s lap and ask, “ya know?” If I had wanted to be part of the magic, I realized that I had to take that one step further…

In my thirties, I was accepted into a mentorship program that paired me with an established and much lauded writer. Let’s call him, Writer. I was intimidated but also so thrilled to be in the Writer’s realm. He set the terms of our engagement. We were to correspond with each other only through letters. We would never meet in person or talk on the phone. This writer did not want to use email, preferring to snail mail their feedback on typed lavender stationary. I readily agreed.

I remember that I would drop my stories in the mailbox and be in knots for days. I would let two weeks pass by and then begin sitting on the porch of my rented house, chain-smoking in my pyjamas until I caught sight of the letter carrier. I lived for those lavender pages.

At first, the letters were kind. My stories came back with margin notes, suggestions for tightening a phrase, using different words. They were minor edits and even some encouragement. I took the feedback very seriously. I re-worked my pieces, spent hours thinking about a particular phrase or the order of paragraphs. I loved it so much that I was buzzing. It meant everything to me that this WRITER was giving me time and faith.

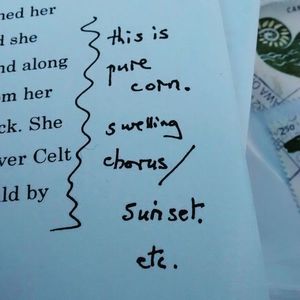

But things quickly turned. The lavender pages started to speak with a different tone. The writer accused a short story of being nothing but a collage of meaningless parts. It did not follow the proper form of story. The Writer outlined a basic template of how a story should be – the components, the order of things, etc. It had the timbre of an adult scolding a child. Remember, I was in my 30s at this point. But I trusted this writer’s assessment. I had never taken a writing course before. All I had were the thousands of books that I had read and let soak me. My knowledge of writing was osmosis. And still, I understood that this story that I was struggling to write was breaking the traditional mode of story. For some reason, my stories were told in fragments and never followed a linear logic. I didn’t know why and had thought he would understand and maybe tell me…

It got worse. The feedback became shrill, and he began to tell me that I lacked compassion for my male characters. I understood that I was a disappointment to him. Sucked into the vortex, I convinced myself that I was wasting the writer’s time, taking away him from his own important work.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

Then, the worst came: the Writer accused me of being incoherent. And I quit.

As a child immigrant, I learned early on that I was incoherent. Language has always been broken for me. I spoke “broken” English, and my Cantonese is frozen in the vocabulary of a 6 year old. Along with language, I experienced my life as fragments, always splintered somehow. There was a before immigration and after. There was a before I was abused and an after. There was racism and sexism that chopped me into many pieces. I didn’t have the ability to tell a seamless story. My life is stitched together inelegantly. You can spread it on your lap, and you will see the threads crisscrossing crudely together across patches of fabric of clashing colours and patterns. My life is a cacophony. The way I write is sometimes cacophony, but it is my life and the way I know how to tell stories.

I didn’t know then how to explain this or how to describe my intentions in the work. In my head, I only heard the big Canadian Writer say my work was incoherent. I boxed my stories and never replied. Months later, he wrote again on a lavender sheet, asked me if I was discouraged. He explained like a benevolent father that writing was this slog, and that this should not deter me from persisting. Real writers persist.

I did not have it in me to get back up and continue this relationship with him or with my own work. I turned to other things. I did a masters degree and then a PhD. I found joy in the academic writing (don’t hate me. I do!) and realized it was simply because I LOVE writing. My first love, my most passionate love, was and is fiction.

Fast forward many years later, and the love for writing fiction continued to tug. I tentatively joined a writing workshop. I re-submitted the story told in fragments. Many of the fellow workshop participants responded in the same way as the Writer. What was it about though? Just a jumble of scenes that go nowhere… But a couple of people liked it. They saw a kernel of what I was trying to do and through their feedback, I acquired more insights into my choices for the piece. So once again, I took the feedback and re-worked it. I submitted it to a short fiction contest of a reputable literary journal and to my surprise, I won third prize. It was the first time I had been published and the first amount of money I ever made from my writing.

This was a turning point for me, a convergence of desires, some long held. I felt for the first time not just as a recipient of literature but in a community of literature. It felt damn good.

I even had another mentorship, this time in Diaspora Dialogues’s Emerging Writers program paired with Rabindranath Maharaj. Rabindranath’s generosity demonstrated to me that respect and care were fundamental to my ability to thrive as a writer. There would also be more workshops that followed.

I often return to the question of coherence and incoherence. For marginalized writers, we may have experienced generations of being displaced from language, literature, and knowledges; so, if we are to centre ourselves in our work, we are often called to have to defend our writing and choices about craft. Sometimes, we will be accused of being incoherent because the modes, forms or languages of our storytelling do not make sense to some readers. This is especially true for those readers who cling stubbornly to European/American (read: White, het, male) traditions of literature. These will be reasons to dismiss our work, and in turn, we need to understand that these are also attempts to expunge our bodies from the lofty spaces of cultural production.

There will always be terms of engagement, as the Writer set out for me a long time ago. So be ready. Learn a lot, listen carefully to the feedback and take what you need, leave behind what will not help you and work it. When you are done, defend your writing. You may find that others will come to the defense too. I realized that our work in stories, poetry and essay have lives of their own. Set them free, and it’s not only readers who get to ask questions. The texts ask questions back. Therein lies the magic I remembered as a child. Books are alive.

Do I regret ever crossing the lavender path of the Writer? Yes and no. Maybe he was just old school or that we were not a good match. Maybe he was just way out of his lane. Regardless, I didn’t know at the time that I also had agency in that relationship. I do not regret that this experience taught me the important lesson that I need to stand by my writing and not let someone else dismiss it as simply “no good”. In its early stages, there should always be space for dialogue with a mentor and reader. You need to let your work speak for you, but before the final draft, you need to learn to speak for it too as part of the process of its development. With experience, my confidence has grown enough for me to understand this dynamic.

There are seeds in every piece of work, even in the rawest forms. We need the space and time to let these seeds grow. We need engaged readers who will get deep into the soil with us to help us nurture them. This is not to say that we will like everything we hear about our work, but it does mean that we need to develop the skills to listen and be able to discern the difference between the nutrient and the manure. Even if it is manure, we need to go back to the text and ask ourselves some questions of the choices we make. Thinking deeply about these choices helps us clarify our intentions and deepen our craft.

And to you, BIPOC writers and other writers marginalized from the mainstream, find the readers your writing was meant for. Let them be the ones to receive your precious gift as intended. Let them guide you on what you need to do to grow it.

I’ve been part of a lot of workshops now, and I’ve even facilitated a few. I’ve learned that feedback is a necessary part of the process and indeed, you DO need readers to make you a better writer. It’s work. Writing is hard work. The Writer was right about one thing – to be a writer, you must be persistent. BUT. You do not need to accept mean-spirited comments or feedback that attempts to destroy you. You deserve the chance to bloom something beautiful. There is still a part of us that is the little grasshopper in love with the word and the transformation it can bring. We need to protect that self. OK? OK! Get writing, friends.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Carrianne Leung is a fiction writer and educator. She holds a Ph.D. in Sociology and Equity Studies from OISE/University of Toronto. Her debut novel, The Wondrous Woo (Inanna Publications) was shortlisted for the 2014 Toronto Book Awards. Her collection of linked stories, That Time I Loved You, was released in 2018 by Harper Collins Canada.