Domestic Epic: an Interview with Ken Sparling

By James Lindsay

To fully appreciate the books of CanLit anomaly Ken Sparling, it helps to think of his work as a single statement told from different perspectives. Each book is a unique view, yet every time we meet a familiar, unnamed family (the man, the woman, the children and grandfather) at a familiar location (an older suburban house buffeted by wind). Characters inhabit this vague world together, rely on one another, but also spend a lot of time being lonely (or maybe they’re just hungry), particularly the father character, who is usually the protagonists. Not fighting or complaining about loneliness, or even naming it, but simply living it, inhabiting it. The overall affect is that of a melancholy domestic epic, a housebound Beckett: people living in a heavy stillness as they move from room to room, place to place throughout the day, interacting with both objects and other people with a similar kind of awkward intensity.

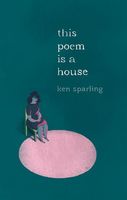

Sparling’s writing is characterized by its sentences-not-stories-style minimalism, often absent of physical descriptions, where the reader’s imagination becomes a more active participant in colouring the story. This style is both embodied and altered in his latest, and first book of poetry, This Poem is a House (Coach House Books). Timewise, this book-length poem feels like a flashback. The characters, “the boy” and “the girl,” are in the beginnings of what could be a long relationship. There are no children this time around, only an empty house that feels too big for two people. Like his other books, the writing is fragmentary, broken up into vignettes that work off of one another but this time with the notable addition of line breaks that heighten the musicality of the sentences.

James Lindsay:

This Poem is a House is reminiscent of your previous books, with its domestic subject matter, location and style, but it's a new form for you. What motivated you to make the jump from prose to poetry for this one?

Ken Sparling:

All we’re really saying here is that I decided not to let my word processor decide where to break the lines. A piece of literature is a series of decisions and I’ve never felt all that comfortable behaving like I know how a piece of writing I’m creating should be organized. I never felt like I had a firm basis for making decisions about the order things arrive in, or the characters who wind up in my work. I think I try to convey that tentativeness in the work itself, so the decision I’m making is to show that the order doesn’t matter… or maybe just order doesn’t matter. Or at least, there’s something in chaos that matters, maybe more than order.

I’ve tried, on past occasions, to decide where to break the lines in my work, the way a real poet does, but it always felt artificial to me, and I think it was because it mattered to me where the line got broken. I felt like there needed to be a reason to break the line where I broke it.

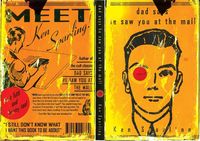

Right from my first book, Dad Says He Saw You at the Mall, I’ve always ordered things more on the basis of the music of the piece than on any sort of narrative concern. But whenever I tried to break the lines deliberately in any piece of writing I was working on, I think I always (god knows why) tried to find a reason for breaking the line where I broke it. I would sometimes ask poets how they decide where to break the line, and the fact that this was a concern for me just shows that I thought there must be some kind of good reason for deciding where to break the line in a poem. Sometimes I come across a poem where the way the lines break seems utterly sublime, but I’m not sure I could say exactly why, and I guess that’s part of the reason why a line break can be compelling, because it doesn’t have to make sense on a level where you could even ask “why?”.

With This Poem is a House, it seems to have finally occurred to me that I could approach line breaks the way I’ve approached section breaks in my previous works, as a kind of search for musicality. And when I talk about musicality, I’m talking about the kind of progressive music – like Bach or BTBAM – where the progression forward is so unexpected – so relentlessly unexpected throughout a given piece – that I cannot by any means figure out what motivated the creator, beyond maybe a feeling of joy. Yet the progression of their music seems always so perfectly right.

So, to answer your question more directly, I guess what motivated me to make the jump from prose to poetry was an expanded capacity for joy that I hadn’t experienced previously – an expanded capacity that comes, I have to believe, from giving up on the need to understand why.

JL:

The poetic structure of This Poem is a House is reminiscent of one of your earlier books, For Those Whom God has Blessed with Fingers, which has a fragmented, aphoristic-like quality to it. Both books were edited my Derek McCormack, what was Derek's influence as editor like on these books and why did you return to him for This Poem. . .?

KS:

I don’t really think of Derek as my editor. His influence goes way beyond anything you could describe in a single word like that. If you have to have a word, I guess it would be friend, but that seems much too weak. If he’s formally acknowledged as editor on certain of my books, and not on others, that’s just misleading. He’s a strong presence in my life, and as such, a guiding force in all my books.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

He’s the first person to read anything I’m working on. If he suggests that I change something, I change it. He introduced me to Beth at Pedlar Press, which published four of my books. He brought This Poem is a House to Alana at Coach House. I’m influenced by his writing – his sense of timing makes everything he writes beautiful, funny, irreverent, human.

Derek, at one point, cut the entire manuscript of This Poem is a House into pieces – literally – and then pasted them back together in the order they are in now in the book.

Having Derek in my life has had a pervasive influence over everything I do. He’s there in everything I write, the same way he’s there in my life, through his companionship, his own writing, his support, his knowledge of literature and art, and his keen eye. I love the guy.

JL:

There is a soft-spoken spiritual theme that runs through many of your books. God or angles sometimes appear, but never interfere with the characters, just observe or comment; yet religion is never directly mentioned. How do you see spirituality in your work?

KS:

You are always just questioning names, I think, when you write. Wondering what the words you use might mean as you settle them into whatever larger piece you are working on. You question them by using them, by positioning them among their fellow words. You aren’t telling a story so much as asking the words what they can offer.

For me, “God” has always been the epitomic example of this writing as questioning. The word “God” is fraught with meaning to such a degree that it approaches meaninglessness. In the world I’m trying to participate in, that meaninglessness is a great opportunity, because it wipes a word clean in a way. It’s not unlike my naming the main characters in the book “the boy” and “the girl”. Although “the boy” and “the girl” are clean of meaning for different reasons than “God”.

When someone says they don’t believe that “God” exists, it seems almost nonsensical to me. It’s like they are saying that they don’t believe that “love” or “health” exist. These are words. They have the capacity to evoke something in us. “God” exists as much as any other concept that has a word attached to it.

Maybe when someone says God doesn’t exist, they mean, at bottom, that the word is so overburdened with meaning that it no longer means anything to them at all, and so God is a kind of emptiness or void. But to me, that emptiness is exactly what makes the word so appealing. The meaning of “God” is exactly that emptiness you experience when you are so overwhelmed with the world, with meaning, that you give up completely on ever arriving at any sensible (available to the senses) meaning. There’s a moment in reading literature when you sink below the surface of the words and float, and the word “God” always feels to me like it has so much potential to bring about that floating moment.

Maybe this is what you are talking about when you talk about spirituality in my work.

Really, as a writer, you don’t have a lot of control over what a reader brings to the words you use. I think probably some of my least favourite reading experiences are ones where the author believes he does have control and seems bent on driving me, the reader, into a corner. I hate it when the author has a very exact path in mind and the writing feels like nothing more than a means of forcing me down that path.

I like when something sounds, on a musical level, as though it is full of meaning, but there’s something not quite sensible in it, and no matter how hard you try, you can’t quite explain what it means.

Spirituality is a vapour. It rises out of that place among the words where the senses fail, yet somehow meaning prevails.

JL:

That's an interesting take. I ask because it's rare to find direct references to God in contemporary literature, especially without religious context, so when God does suddenly appear, it's startling. It forces the reader to confront the gravity of this presence and all the meaning or meaninglessness that comes with the word. So I can't help but think of this as a form of spirituality, a personal form that the readers have to build for themselves. You mention not wanting to force your readers down a path. How do see you relationship with readers? If not force them down the path, how do you try to guide them?

KS:

What if I told you I have no real interest in guiding the reader? That I’m really just trying to find a way for myself?

I want to say that the words I write form little communities and that the way the words come together and meet each other on the page – the way they gather in groups, arrive at the end of a line, veer away from each other in places – constitutes a form of community, so that even on a cellular level, my writing is a recommendation for a way of interacting. And when I call my writing a recommendation, I mean I want my writing to stand as an example. It’s an example of a way of arriving at the place where you already are right now and then proceeding as though you don’t know what is coming next.

Dave Grohl says of Led Zeppelin drummer John Bonham, that he “played the drums like someone who didn’t know what was going to happen next – like he was teetering on the edge of a cliff.”

That’s the way I want to write.

I want my words to be friends with each other, but friends only in the strongest sense of the word. They might jar against each other, or crash, or fall away off a cliff, but then that’s really exactly what I’m recommending. Step up to the edge of now and wait quietly.

I don’t want to be included in a reader’s plans, if those plans involve finding in a book any form of guidance, even it’s simply a form of narrative guidance that connects one moment to the next. I want a reader who expects me to disrupt his or her plans, a reader who comes to literature hoping for disruption. And, in return, I expect that the way the reader reads will be an act of disruption.

I want my writing to be a way of looking into the empty space in front of me in a manner that makes the reader want to look there with me.

I want to arrive with the reader at any given moment in the written work as though we haven’t already arrived at a place where we were always going to be; as though we haven’t made up our minds about anything yet.

I want to wonder always what makes for a strong community – a strong community of words, a strong literary community, a strong communion between writer and reader – and never feel like I’ve arrived at the end of that wondering.

I’d like it if my writing acted as an invitation to the reader to join me in that wondering.

JL:

So then what role does narrative play for you? Do you ever start with a story in mind, or do you let the words do the work?

KS:

I don’t start with a story in mind. I start with a moment that appeals to me – maybe a brief exchange between two people, or a person looking out the window with their face in a certain light in the living room – and I try to go from there. Some sections of my books wind up reading like little stories. But the way these little stories evolve is pretty close to what Dave Grohl said about John Bonham. I’m constantly running up against the edge of where I’m going and moving forward blindly. There’s no story idea to guide me. It just doesn’t appeal to me to first figure out a plan for getting to where I’m going, and then follow the plan.

At the same time, I think I wonder about story constantly. And not just in my writing, in everything I do. What constitutes a good story? What interactions have meaning, and what sort of meaning do they have, and how do we come to believe that a given moment has meaning? Does something become story as soon as I clothe it in words? Is this a story right here that I’m handing to you? Does something become a story as soon as I put it into words? If I write, “My name is Ken,” is that a story? If I add a sentence: “My name is Ken. Yesterday I rode my bike,” does that turn it into a story? Is the one more meaningful than the other? If my story is three sentences long and followed by another three-sentence story, what does that mean? Are the two stories connected somehow? Or does one simply follow the other on the page?

For a lot of what I do in my life, mainly at work, I’m simply an extra limb on the body of people who have big ideas and need a lot of arms to make those ideas a reality. There are plenty of people around who are bent on making certain things happen by creating and following a plan. The world doesn’t need any more of these people. We have enough of them that I feel like I can safely abdicate any responsibility I might ever feel for coming up with big ideas and planning out a way to make them happen.

Writing is a place I can go to be free of all that. The last thing I want to do with my writing is to emulate the people with big ideas and big plans.

The Toronto launch for This Poem is a House is June 10 at Page & Panel: The TCAF Shop. Ken will also be reading at Unnamable Books in Brooklyn on July 12.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

James Lindsay has been a bookseller for more than a decade. He is also co-owner of Pleasence Records in Toronto, a record label specializing in post-punk, odd-pop and avant-garde sound pieces.