Don’t Know Much About History: Memoir Crazy

By Dalton Higgins

Literary fiction and poetry are cool, but non fiction biographies are becoming cooler. Again. Some of us bookish geeks and authors tend to spend an inordinate amount of time tracking publishing industry trends, and as a biographer – I’ve written both an autobiography and an unauthorized biography - there’s no question that there’s this newer disproportionately large bulk of readers interested in reading about the private lives of public figures.

Years ago critics called this phenomenon the Memoir Craze, as books involving ginormous thought leaders like the late Steve Jobs seemed to capture the imagination of readers arguably more so than your typical fiction fare. And there’s this new book Why We Write About Ourselves, edited by Meredith Maran, where 20 memoirists wax personal about why they choose expose themselves and others in their art.

Think about it. When pop culture giant and iconic musician Prince passed away, outside of the usual mourning process that many of his fans endured, I’m not sure if it was the scribe in me or not, but the first thing I thought was; are we ever going to get to access his Beautiful Ones autobiography manuscript that Spiegel and Grau were slated to release in the Fall of 2017?

Whether it be first person authorized memoirs or unauthorized biographies, in both cases, you need to get the facts right, so these tomes can hold their weight as good historical markers. And it’s a painstaking process. If you were to tell your own story in book form, would you be able to get all the facts right? If your long term memory is not so good, then the biography may not be so good either. And then all kinds of revisionist histories might reveal themselves. Attempting to rewrite the particulars of one’s faded past is no easy task. Can your fact checkers contest the facts from your memory banks?

Literary documentarians, biographers, memoirists are needed more now than ever. If all of these illustrious historical moments triggered by some select iconoclasts aren’t documented, it will feel like these moments didn’t happen, and that they didn’t really exist. Sure, passing down oral histories is hugely important too, and performs a certain function in various cultures, including my own (Jamaican) and Indigenous communities. But then there might also be something to be said about having a written document that will outlive our own mortalities, and that can be used for posterity and educational purposes, canonized, and stuck in libraries and other reading destinations for future legions of youth to learn their own histories.

When a prominent long time African Canadian community leader, father, activist and music entrepreneur Howard Matthews passed away on August 31st, I was asked by his family to put something together, some words that could attempt to characterize his life. In some ways it felt like I was writing another biography, but rather than having 228 pages to play with – that’s the page count for my Drake biography Far From Over – I had about four. Given the scarcity of publishing contracts being offered to African-Canadian authors in Canada coupled with the extremely low rates of discovery of emerging black authors, I am sometimes tasked with having to accommodate all kinds of requests to mentor upcoming writers or crank out some pertinent cultural copy for the good of the community. It’s a responsibility I take very seriously, and I will continue to do it out of both choice and necessity.

Here are some excerpts from the tribute piece I wrote to honor one of the Toronto black community’s great leaders who entered the spirit world on August 31st. I never wait until Black History Month to disseminate our histories, in fact I do this year round ’round here:

There aren’t nearly enough words to express the vast contributions that Toronto’s late cultural pioneer Howard Matthews – who entered the spirit world on August 31st, 2016 – made to local city life in general, or to the black community and the overall Toronto area music scene in particular. That would require a 288 page biography. But in my effort to preserve, document and disseminate crucial black Canadian history, I present to you the life of Howard Matthews. Black lives really do matter.

Those in the Canadian cultural know have understood that for the last four decades, Howard was a trailblazer, a renaissance man, and a man of firsts. That might’ve had something to do with his adoration of the world’s first global black civil rights icon, the late Marcus Garvey, who was a Jamaican wordsmith and entrepreneur able to connect the entire African Diaspora through his words and actions.

As is the case with most renaissance men, who engage a very wide range of incalculable interests, some people only know them through their public contributions to cultural life, as was Howard’s case, being primarily known as an artist manager, restauranteur, tireless community worker, fundraiser and father. But these descriptions don’t tell the whole story or do him justice. Howard had also at one time or another been a model, actor (CBC), cook (Western Hospital), and rated films for the NFB (National Film Board) switching with ease between a dizzying array of roles and jobs covering his storied lifetime.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

But back to the firsts.

Some know the St. Kitts born Howard as the devoted husband of Broadway star and jazz and blues singer Salome Bey “Canada’s First Lady of Blues”. Married to singer Salome Bey on April 7th, 1964, that year Bey moved to Toronto to be with Matthews. She thus began a highly successful solo career and he served as her manager. Out of their marriage and lifelong union, they had three children and one grandchild. Their son Marcus Malcolm Matthews lives in St. Kitts, while their two daughters, Saidah Baba Talibah aka SATE and Jacintha Tuku Matthews are Toronto based vocalists. Clearly, the apple did not fall far from the tree.

From the time he entered show business, some would argue that making a mark on Toronto’s cultural, entrepreneurial and music life was his fate and destiny. In 1947 at the age of 12, the first person Howard Matthews met when his family arrived in Toronto from St. Kitts was the late legendary jazz drummer Archie Alleyne. Archie sat one seat ahead of Howard when they attended Lansdowne Public School and they carried on a lifelong friendship. The two friends once even shared a house at 260 Church Street with renowned Canadian architect Harvey Cowan.

By the late 1950s, Howard had co-founded The First Floor Club, an upstairs after-hours spot located at 33 Asquith Avenue near Yorkville, in a coach house just east of where the Toronto Reference Library now stands. It was at this club in 1961 that Howard first met his eventual wife vocalist Salome Bey, when she showed up with her brother and sister, Grammy Award nominated Andy Bey, and vocalist Geraldine Bey, (or Andy Bey and The Bey Sisters as they were called) looking for a jazz drummer named “Archie Alleyne” they had heard about. Andy and The Bey Sisters had just performed at Toronto’s Colonial Tavern before heading to the First Floor Club. At the front entrance of the club they encountered one of the club’s owners, Howard Matthews. And the rest, as they say is history.

Their home and restaurant (more on that later) was a cultural hub for many local and international traveling entertainers, professional athletes, politicians and music industry titans to gather. Out of the plethora of organic networks built, and connections made at their home and restaurant, there is one well documented tale of local urban legend that arguably stands out from some of the rest. And it involves how multiple Grammy winning bluesman BB King actually first met fellow blues icon Lonnie Johnson. It was at Howard Matthews house! He was hanging out in Howards kitchen with fellow music luminaries Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry as recounted by Canadian music industry veteran Richard Flohil in his book Louis Armstrong’s Laxative and 100 Mostly True Stories About A Life In Music.

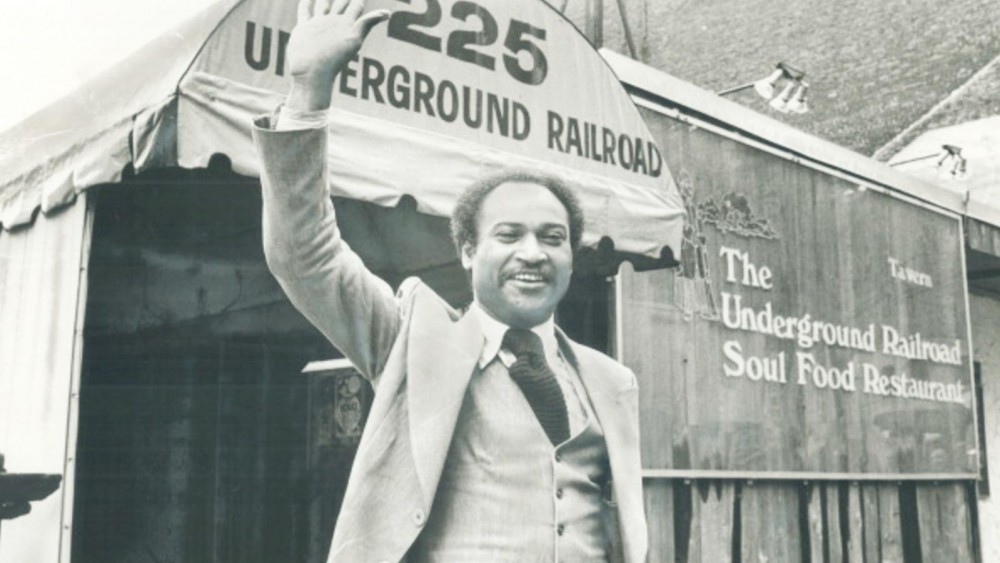

Others knew Howard as part owner of “Toronto’s first soul food restaurant” – The Underground Railroad – where all of this spontaneous magic happened. The restaurant opened on February 12, 1969, and became one of the city’s best-known restaurants for over 20 years, where locals took out-of-town guests to rub elbows with celebrities and professional athletes. Howard was one of the four partners in the business, alongside the late Archie Alleyne and two former Toronto Argonauts football stars, quarterback John Henry Jackson and kicker Dave Mann. The first location of the Underground Railroad was 406 Bloor Street East and had 60 seats for in-house dining. The restaurant then changed locations in April 1973, moving to 225 King St. East to accommodate up to 200 patrons. “Southern fried chicken, barbecued ribs, black-eyed peas and collard greens,” Alleyne said of the menu, when being interviewed by John Goddard of the Toronto Star. His love for providing unique cultural dining experiences continued well on into the early 2000s when he worked at Southern Po Boys. Before becoming an established restauranteur, as a gregarious and admittedly troublesome teenager, Howard had actually learned to cook when he was sent away to a boy’s reformatory school in Bowmanville (Ontario Training School for Boys). After working odd jobs, he and a business partner opened the First Floor Club, a jazz club in a former coach house on Asquith Avenue, and later turned the Kibitzeria restaurant, near the University of Toronto, into a blues bar. Then from 1969 to 1979, he helped run the restaurant portion of the business.

By the late 80s, Howard became one of the co-founders of CAN:BAIA (Canadian Artists Network: Black Artists In Action), the first black national multi-disciplinary arts organization that worked to promote black artists both nationally and internationally. Certainly, honoring those among us, and those who came before us, was a long running theme throughout Howards life. By the early 2000s, perhaps many young and old black entrepreneurs and/or emerging jazz, soul and blues music industry enthusiasts, musicians, and change makers, were already standing on the shoulders of greats like Howard that came before them, and didn’t even know. But they do now. By 2005 Howard had a stroke and suffered from Aphasia. He became a resident of the Lakeside Long Term Care home along with his wife Salome and eventually passed away on August 31st 2016.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Dalton Higgins is an author, publicist and live music presenter whose six books and 500+ concert presentations have taken him to Denmark, France, Curacao, Australia, Germany, Colombia, England, Spain, Cuba and throughout the United States. His biography of rapper Drake, Far From Over, is carried in Cleveland’s Rock n’ Roll Hall of Fame & Museum collection, and his Hip Hop World title is carried in Harvard University’s hip hop archive. His latest book is Rap N’ Roll. For updates on Dalton Higgins’ writing, follow him on twitter: @daltonhiggins5