Gwaandak

By Lily Quan

This started off as a straightforward article about Gwaandak Theatre, Yukon’s only Indigenous theatre company. But something went wrong. Or right.

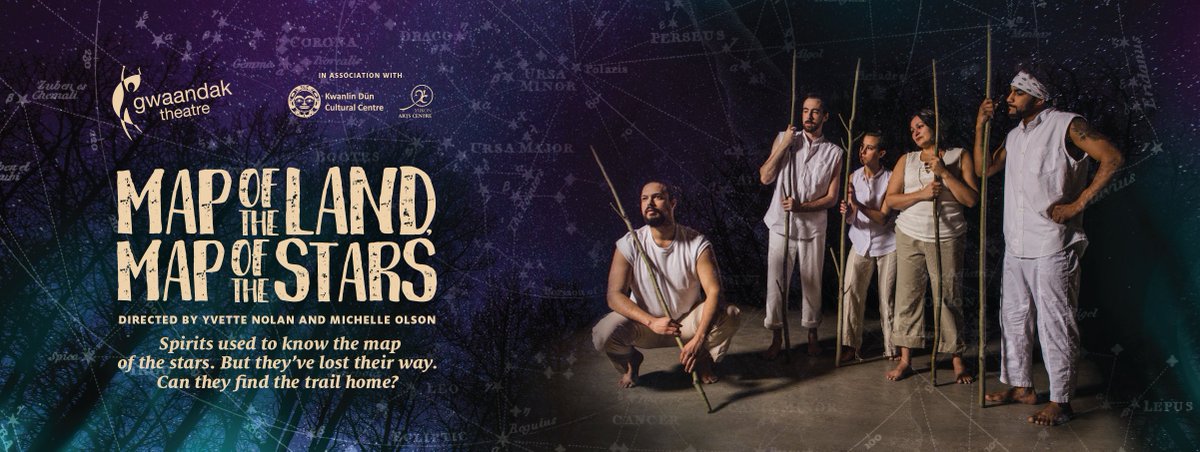

I wanted to feature Gwaandak’s production, Map of the Land, Map of the Stars, which will tour Ontario this fall. In a broad sense, Map of the Land reflects the theme of struggles on the land since colonization. The play is episodic and non-linear, travelling through different time periods such as the Klondike Gold Rush. It involves movement, music, dance and spoken word. The seven-person ensemble piece was performed in Whitehorse this spring to rave reviews. But I ran into a problem. As I researched the play and read the background material, it wasn’t clear what exactly the main message or moral was.

I sat down to discuss the play with Patti Flather, Gwaandak’s co-founder and artistic director, and Andrameda Hunter, one of the play’s directors. For an hour and a half, the women talked about the collaborative process in creating Map of the Land, the inclusion of everyone’s voices and the respect each member had for each other’s contribution. Meanwhile I kept asking, “But what’s the play about?” I never got the simple answer I wanted.

Then I had a Eureka moment: a simple message wasn’t the intention. In Indigenous culture, the learning is circular.

It goes back to the storytelling tradition. (“Gwaandak” in Gwich’in language means “storyteller.”) According to Andra, elders in a family will tell the same story again and again over the years. People will take from the story what they need to learn at the time, learning something different with each retelling. This storytelling tradition is complex, with many layers, rather than being a simple mirror of the narrator.

When I saw video footage of the play, it became clear Map of the Land is much the same way. The production presents an experience that is layered – there are visuals of Yukon projected on screen such as animal hides and fish hooks during a story about the Gold Rush, for example – and the audience members will follow the thread that speaks to them at the time, be it the storyline, the visuals or the music. According to Gwaandak’s notes, “Your neighbour will not have exactly the same experience you do; in fact, it is likely no 2 people in the room will.”

I realized after the interview in the coffee shop that Patti and Andra were in fact presenting to me what was important to them about Map of the Land: community, collaboration and respect for each person in the group, values that are important to Indigenous peoples. The lesson that I learned is that Gwaandak’s commitment to a First Nations focus is reflected not only in what it creates but how it is created it as well.

Gwaandak Theatre has been championing Northern and Indigenous voices since it was founded in 1999 by Patti Flather and her husband, Leonard Linklater, a member of the Vuntut Gwich’in clan. Both of them are award-winning playwrights. Gwaandak has taken a leadership role in Yukon theatre, providing training and encouragement to artists, particularly those who are First Nations, and providing an outlet for stories that might not be heard otherwise. Falen Johnson, a Six Nations playwright, says, “I love Gwaandak. It’s a place where you know you’re immediately welcomed as an Indigenous playwright.”

In recent years, Gwaandak has commissioned scripts by Indigenous playwrights and has produced plays that have toured nationally including The Hours That Remain by Keith Barker about the disappearance of Indigenous women on the infamous “Highway of Tears.” Map of the Land, Map of the Stars was a production that was two years in the making. It will be performed September 29 and 30 in Kitchener as part of the IMPACT 17 Festival and Talking Stick Festival in Vancouver in February 2018.

Canadians have shown greater empathy for First Nations peoples recently and Gwaandak’s work has been attracting greater attention in the territory. However Patti believes there is a long way to go. The danger is that people now think “everything is all better.” She believes there is still pressure on Indigenous people to teach others about their culture and the extent of the pain created by the residential school system. Patti sees Gwaandak’s role as a community-builder. She hopes to tour future productions to reach wider audiences not only nationally but also locally by touring the rural communities of Yukon, so that everyone gets a chance to hear the stories that are waiting to be heard.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Lily Quan is a writer and editor based in Whitehorse, Yukon. Her work has appeared nationally on CBC Radio and The Globe and Mail. She runs the annual Northern Lights Writers’ Conference, whose featured authors from down south have included George Elliott Clarke, Terry Fallis and Andrew Westoll. For a glimpse of her past adventures in Yukon, visit sourdoughwannabe.wordpress.com.