Happy Birthday, Marian Engel!

By Ben Ladouceur

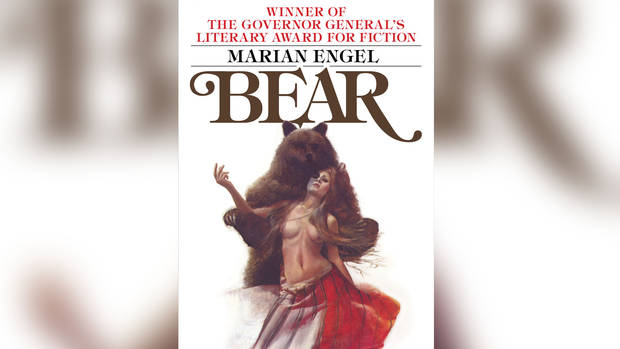

Today is the eighty-fourth birthday of Marian Engel, or it would be, had the novelist not died of cancer in 1985. Now, instead of a person, she is a name, survived like all people by her family and friends, survived like all artists by the works she produced. However, the task of survival is not distributed evenly across her body of work. Some of her books survive more fulsomely than others, in bookstores, in syllabi, in the folklore of the bookish. For Engel, one particular novel gets the lion’s share of attention. Or, uh, the bear’s.

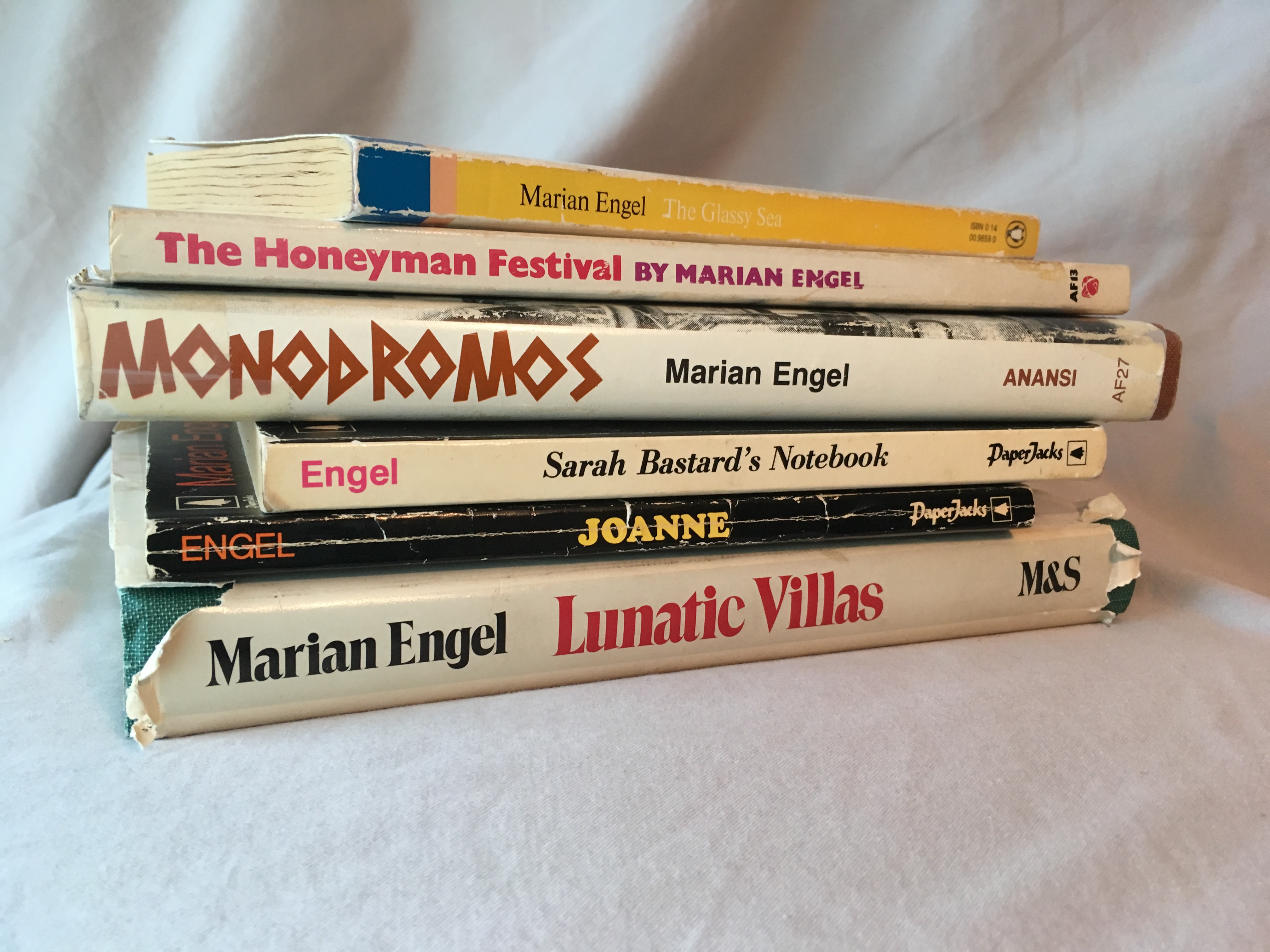

In addition to the Governor General’s Award-winning Bear, Engel wrote five other novels, as well as several curiosities – a short story collection, a few children’s books, a coffee table book about islands, a series of dramatic one-woman radio broadcasts that was released as a novel-like thing called Joanne: The Last Day of Modern Marriage.

Like most of her readers, I started with Bear. I read it back in 2008, when the circulation of its notorious elevator pitch (“Woman fucks bear on remote island”) was still confined to the English department lounges of Canadian universities. Having heard these whispers, I opened the book all anxious and impatient for some bestiality to somehow go down in the confines of a well-regarded, award-winning Canadian novel.

I was disappointed by the lack of bear sex on page one. I was disappointed by the lack of bear sex in the book’s whole first half. It does happen eventually, and so does lots else. When I think back on the book now, a decade later, I don’t recall the porn quite as vividly as I recall the wit and the musings of Lou, our archivist protagonist, whose mousy premise is further and further complicated with every moment we spend in her head. Early in her courtship with the bear, she reflects on an old relationship: “For a week, she had loved the Director. For longer than that, perhaps. Certainly she had been in need of a sexual connection. Cucumbers, she had found on investigating the possibilities suggested in Lysistrata, were cold. Women left her hungry for men. The Director shared her interests, was charming and efficient; they had much in common when they fucked on Molesworths’ maps and handwritten genealogies: but no love.”

I think of Bear as the story of a lackluster solution (fuck a bear) to a universal problem (feel whole; feel peace). I have never read a love as unrequited as Lou’s love for her bear, which reaches beyond the human to something that is safer and also less safe. But that’s just me. Ten people, I’d wager, will have ten different takes on the novel’s ambiguous morals. There’s no summing this story up.

That’s why it’s so unfortunate that back in 2014, an Imgur page about the book entitled “What the Actual Fuck, Canada?” went viral. In an attempt to account for the suddenly-notorious book’s existence in the Can lit landscape, many writers read and wrote about the book, generally concluding it was more than its pornography. But what was missing, then – and what Engel’s birthday gives me an opportunity to provide, now – was a look at the rest of Engel’s output. I would posit that Bear isn’t her best book, and not even her most transgressive.

After I read Bear, I read another of Engel’s novels, The Honeyman Festival. Again, this was before her memeification. She was then most readily compared to Phyllis Brett Young, or Joan Barfoot, or Janette Turner Hospital: a perfectly capable Canadian novelist, championed by her own share of Can lit academics, with paperbacks found easily enough in many of Ontario’s used bookstores. What little sex takes place in Honeyman is human-on-human. Nonetheless I found (and find) Honeyman more defiant and more daring than Bear. Protagonist Minn is pregnant with twins and unhappy about it. Her husband is away for months at a time, and the two children she already has are described in parasitic terms. She’s gonna have four kids in total – that’s too many, and she knows it. However, the book isn’t a testament to the horrors of motherhood; there are much more terrifying examples of parenting-as-living-hell in literature. (I think of the demon-like baby in Joyce Carol Oates’ “The Guilty Party,” pounding on his exhausted mother’s breasts: “Momma damn you don’t you try to hide, you can’t hide from me, damn dumb bitch don’t you know who I am! And I’m hungry!”)

Rather, Minn’s distaste for her own motherhood and pregnancy is as ordinary as the hay bales on the wallpaper. Contemplating her weight gain, Minn performs the following inventory of her dietary intake: “There was beer in the afternoon after wiping the nap-shit off the walls, and peanut butter sandwiches when they got her up at night, and eating their leftovers, and guzzling and stuffing when you were too angry to consider hitting them.” If Bear gives a voice and a face to the most outlandish taboo you can think of, then Honeyman tackles a different taboo, one that is less shareable, less laughable, and perhaps even less comfortable: regret towards motherhood, resentment towards kin.

While Honeyman disrupts notions of motherhood, another Engel novel, variously released as Monodromos or One-Way Street, disrupts notions of marriage. Audrey Moore is abroad, visiting her estranged husband, a failed musician and total queen. Again we’re on an island, but instead of a lake in the Canadian boonies, the island is found in the Grecian coast. However, Ontario looms large outside the frame, as Audrey’s home and oft-cited reference point for ordinary humanity. In attractive environs, and in the company of attractive people, Audrey wonders what it means to be a visitor, a foreigner, a stranger, a loner. Her musings are decidedly lighter-hearted than Minn’s, and the book is possibly Engel’s funniest as a result. As with Bear, Monodromos culminates in a set piece between a woman and an animal, but it’s a mule instead of a bear, and slapstick instead of sexual.

The Glassy Sea is, in contrast, a showcase of Engel’s abilities as a tragedienne. Its protagonist, Marguerite Heber, begins the story by joining the convent. This sounded like an old-fashioned premise even when the book was published in 1978, as Engel’s follow-up to Bear; the anachronistic look of the black-and-white habit is not lost on Marguerite, whose fellow sisters are aging, dying, declining in number. Eventually Marguerite opts for a more current life path, at the possible expense of her soul’s reputation. Enter motherhood, alcoholism, divorce, disenfranchisement, and more that would be jackassy of me to reveal, in case you ever find a battered copy at a used bookstore. It suffices to assure you that you’ll cry if you’re a person who cries at books. Engel’s other books are fun in the moment, but I’ve found that The Glassy Sea has stayed with me the longest, as a sort of friendly ghost. It’s easy to think back to, especially on car rides through Ontario: “And the ditches are foaming with wild madder, and there are lupines, and the Queen Anne’s lace is opening,” observes Marguerite; “It is a life’s work to keep an eye on a field.”

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

Musings about Ontario, its flora and fauna and populace, recur throughout Engel’s body of work – about Ontario specifically, not Canada in general. Engel’s fascination with the experience of the European-descended Ontarian is sort of wild to me. Even in the province’s literature, you don’t often find such specific interest in this enormous and flat stretch of green-and-brown land, with its handful of cities found mostly in the bottom corner. Canadians from elsewhere – First Nations, the Maritimes, the Prairies, the North, Quebec, the west coast – can proudly list differences between citizens of their own region and the rest of Canada, but Ontarians so often mistake their own experience for something nation-wide. Engel’s persistent differentiations speak to the value and uniqueness of her thought process.

So maybe keep an eye out for these titles in used bookstores, after Endicott, before Findlay. In addition to the novels I have mentioned, there’s her first, a scrappy bildungsroman called Sarah Bastard’s Notebook (also published as No Clouds of Glory), and her last, a well-populated farce called Lunatic Villas (also published as The Year of the Child). Lunatic Villas takes place on a side street in Toronto’s Ward 21, close to an apartment on Dupont St. wherein I read most of these books, and not too far from Marian Engel Park.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Ben Ladouceur is a writer living in Ottawa. His first collection of poems, Otter (Coach House Books), was selected as a best book of 2015 by the National Post, nominated for a 2016 Lambda Literary Award, and awarded the 2016 Gerald Lampert Memorial Award for best debut poetry collection in Canada. Ben is the prose editor for Arc Poetry Magazine.