In Praise of Chapbooks

By Manahil Bandukwala

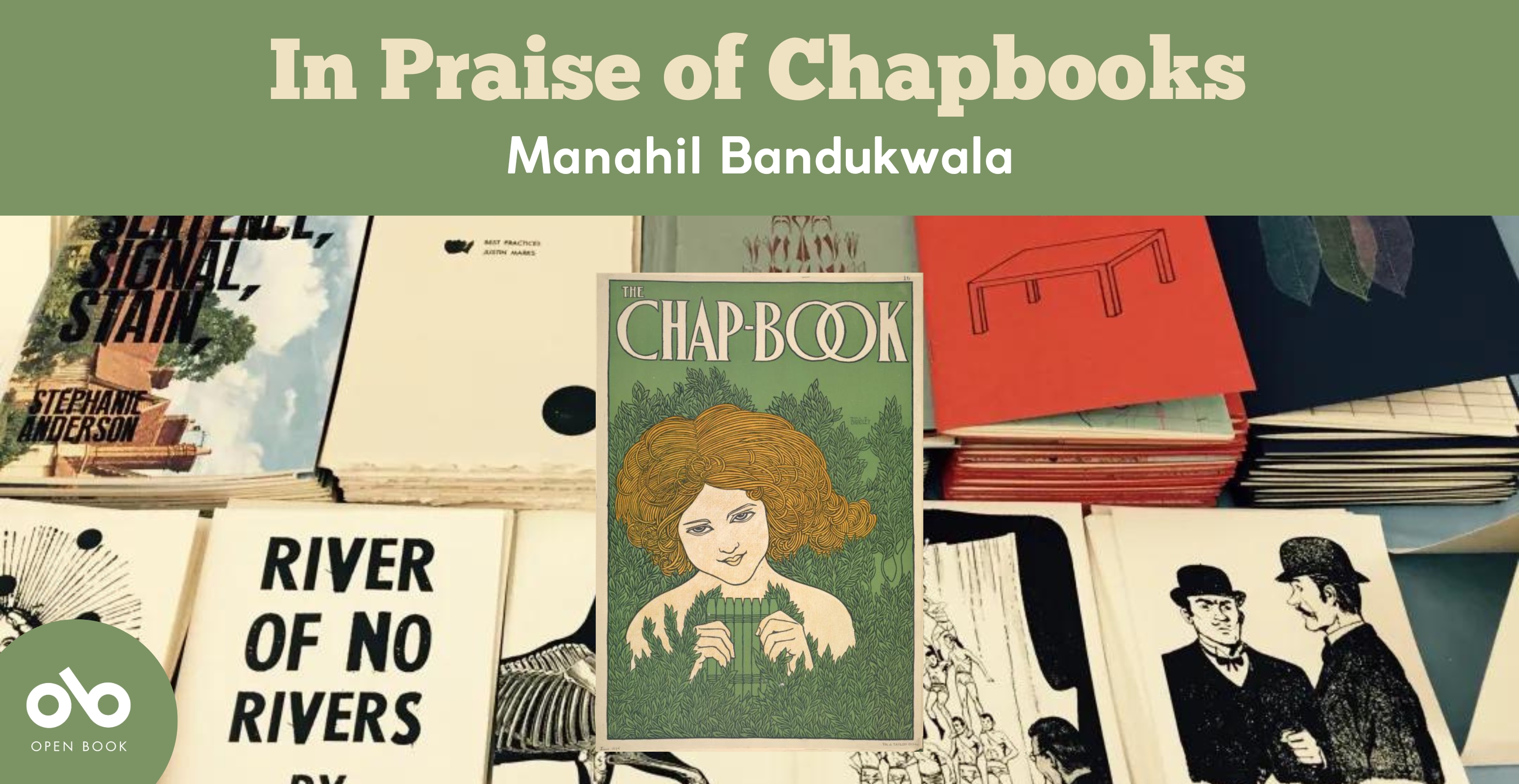

The first time I heard the word “chapbook” as a new poet, I was pretty sure I misheard things. It was a word that everyone working within poetry seemed to know—and because of that, I felt shy asking what it meant. Once I started getting involved in the world of Canadian poetry, I quickly learned what a chapbook was, who published them, and how to create one. Now, I have a shelf full of chapbooks from poets across Canada and beyond.

Shorter than a trade book, a chapbook usually runs from 10-30 pages. While there’s nothing limiting a chapbook to only one genre of writing, poetry chapbooks are typically the most common ones. In this article, I’m going to talk about some of the benefits chapbooks have brought to my writing life, and shower praise on the publishers who work tirelessly to ensure chapbooks persist!

I’ve published my share of solo and collaborative chapbooks. Some have been standalone, while others have been precursors to bigger works. All in all, they’ve been a midway point between publishing individual poems in literary magazines and a full-length collection. As an emerging poet, working with fewer pages made the process of putting together a manuscript less intimidating. I was able to try out working with broader thematic arcs and narratives, an aspect that has continued as I write full-length poetry books. Being able to play in the chapbook sandbox was instrumental in removing some of the fear that comes with taking on large writing projects.

Distribution for a chapbook is small and print runs are limited, meaning a chapbook often reaches local community and is usually out of print within a year. While this can seem like a downside, especially to those outside of the poetry community, the limited nature of chapbooks has a certain appeal to me. I’m grateful to the chapbook publishers who took a chance on my writing when I was starting out as a poet, but I’m also glad the poems I published in those early chapbooks aren’t in circulation anymore. Having tangible poetry to distribute helped get my name out and solidify myself as a poet, but my skill level has also advanced from those early poems.

This isn’t to say that the quality of poetry in chapbooks isn’t as high as trade poetry collections, or that chapbooks are only a stepping stone for emerging poets. Poets of all levels publish chapbooks. They’re a unique space, often with possibilities for experimentation and play that aren’t always available within trade presses. Chapbooks are much more approachable, whereas just submitting a full-length manuscript and waiting for a response can take years. Sometimes, poetry warrants an immediacy that chapbook distribution can meet.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

Poets with chapbooks can also access opportunities for touring, funding, and reading that might not otherwise be possible with single magazine publications. In a world where poetry is almost never the primary focus, this lower barrier of entry makes chapbooks a great way to keep publishing and sharing, without the demands of trade publication. I’ve loved working with my trade publisher too, but there is a certain need for time and energy that isn’t always available in that space. This makes chapbooks an option that always feel available and accessible regardless of what life looks like at any given moment.

But unlike trade poetry (and trade presses in general), chapbook publishers aren’t often eligible for funding to operate (yes, most Canadian presses operate through arts funding). This means chapbook publishers are usually working out of pocket, as sales rarely cover costs of printing, advertising, editing, and so many other aspects involved in running a press. This also means chapbook publishers come and go.

In this way, they’re not that dissimilar to chapbooks themselves. Ephemeral, necessary, and to be appreciated and valued for the brief time they’re around. Chapbook presses are always going to be an instrumental part of creating and sharing poetry, whether with our peers or beyond. So let this post be a note to go buy a chapbook or five, and enjoy in the fleeting nature of poetry!

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Manahil Bandukwala is a multidisciplinary artist and writer. She is the author of Women Wide Awake (Mawenzi House, 2023) and Monument (Brick Books, 2022; shortlisted for the Gerald Lampert Memorial Award), and numerous chapbooks. In 2023, she was selected as a Writer's Trust Rising Star. See her work at manahilbandukwala.com.