In conversation with Margie Wolfe, publisher of Second Story Press

By Dory Cerny

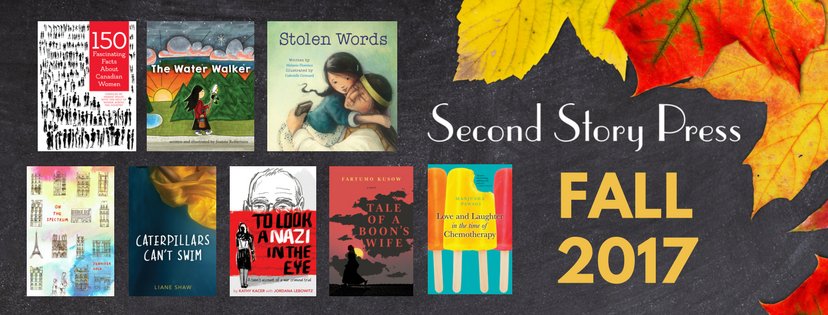

For almost 30 years, Second Story Press has been at the forefront of publishing books that champion feminism, social justice, and diversity. Orchestrating these efforts is publisher Margie Wolfe, who – along with being a past-president of both the OBPO and the Association of Canadian Publishers – is a recognized champion of telling the stories that others might not dare to tell. In June, Wolfe was recognized by the Canadian Civil Liberties Association for her part in “building a vibrant and inclusive society,” while October saw the Canadian Children’s Book Centre holding a fundraising dinner with Wolfe as the guest of honour, celebrating her four decades of “passionate advocacy for social justice, women’s issues, Holocaust remembrance, as well as her inspiring contributions to Canadian children’s literature.” And, Wolfe proudly tells me, Second Story is the first Canadian publisher ever selected to publish a title for Anne Frank House. All About Anne, for which Second Story holds North American rights, will publish next year.

It would be safe to say that Wolfe, first with Women’s Press and – since its founding in 1988 – with Second Story Press, has always been a woman ahead of the times. While the last few years have seen children’s publishers paying more attention to issues of inclusivity and diversity, a quick scan through Second Story’s backlist shows that these principles have long formed the backbone of the press’s mandate, a mandate that continues to evolve and broaden with time. In addition to titles focusing on the Holocaust (including The Promise, a story about Wolfe’s mother and aunt co-authored by Wolfe and her cousin Pnina Bat Svi and illustrated by Isabelle Cardinal), books in Second Story’s spring 2018 list include the middle-grade novel Krista Kim-Bap by Korean-Canadian author Angela Ahn and Ten Cents a Pound, a picture book by Vietnamese-Canadian author Nhung N.Tran-Davies, illustrated by Josée Bisaillon. Recently published books for young readers have focused on autism, teen pregnancy, mental illness, and the Residential School System.

Second Story’s track record and Wolfe’s dedication are well known, but, as the recent controversy surrounding an ESL guide accompanying Second Story’s graphic novel adaptation of Susanna Moodie’s Roughing it in the Bush illustrates, even the most practiced proponents of diversity can stumble in the quickly shifting landscape of socially and culturally acceptable terms and attitudes. I wanted to ask Wolfe, who earlier this year spoke about editing and publishing Indigenous authors at the Writing Stick conference in Alberta and the Indigenous Editors Circle and Editing Indigenous Manuscripts workshops at Humber College in Toronto, about how she (and by extension, other publishers) can move forward in publishing diverse texts respectfully.

Dory Cerny:

For almost 30 years, Second Story has been putting out books with a focus on inclusivity and diversity. Do you feel like you were ahead of the trend?

Margie Wolfe:

Diversity and those kinds of issues are not new to us; it’s not trendy. We’ve been doing this, as you say, almost three decades. And mostly we do it, I think, very well and are regarded very well, in the various communities for the work that we do.

DC:

Where are you finding your diverse creators?

MW:

Well, we have now both an Indigenous writing and an Indigenous illustrating competition, so those books will be coming out in two or three years. To some degree, the reputation that you know about us, so do writers. And so a book that we’re doing this spring called Ten Cents a Pound is written by a wonderful woman who came over as a Vietnamese refugee with the Boat People and she’s now a surgeon in Alberta, and she said we were the right publisher for her work so she submitted to us. And that happens more and more. Certainly we go out and look. We have a beautiful book – I saw this woman’s work on the internet; she’s an artist – and she’s from the black community and I loved her work and contacted her and she’s doing a book for us on black women who dared. So I think it’s a combination of different things, but for sure, people know who we are and what our mandate is. People don’t come to us for bunny stories; that’s not our reputation. After looking at 15 or 20 books, there is a really clear pattern of what our mandate is and what we want to do and what we would be open to hearing about. We continue always to broaden the base of our authors in terms of the communities that we’re doing and trying to deal with the subject categories as we understand our own reality in Canada.

DC:

How have things changed since you started out, in terms of representation and diversity in publishing?

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

MW:

I think one of the big differences is that when I first started in publishing, people thought you didn’t do these kinds of books for kids, or women’s stuff would be a fad. I was told that more than once. And I think we have made our place in the industry, doing exactly what we do and not really diverging very much. We’ve expanded the definition of what all of that encompasses. Part of the reason that we started doing kids’ books is that we wanted kids to have a literature that would take them to adulthood in a way that would make them more concerned with issues about equality and social justice, and they wouldn’t have to be convinced of that in adulthood, that it would just be part of their own growth from childhood to adolescence to adulthood.

DC:

And on the practical side?

MW:

I think best practices, how you do things, evolve, and we all need to recognize that something that we did a couple of decades ago will not necessarily work now. For us, we had what we called the First Nations series for young readers, where we did biographies in various categories, but not necessarily written by First Nations writers. I don’t think we would do that again. Those books were good and they worked, and we’ve published them for the better part of a decade, but now, part of the reason we have the Indigenous writing competition is that we’re very keen to publish the work of Indigenous writers themselves. So that happened. And even in terms of the language, the language continues to change. A decade ago we were talking about First Nations people and now we talk more about Indigenous. And so, we all have to accept that there is a process and that something that might have been acceptable a few years ago, even when you were trying to be as progressive as possible, is not necessarily the best that you can do today. And that will change a year from now or two years from now.

DC:

But in publishing, you’re working two or three years ahead. Knowing that things can shift that quickly, how do you prepare for that?

MW:

There may be things that you might make a mistake on, but unfortunately that’s part of the process, we just hope to make smaller mistakes. We are looking at working with Indigenous consultants, even in trying to do the outreach. We hired someone who’s within the Indigenous community to help us to reach the various organizations so that they can learn that we are having these competitions and that we want to see that work. One has to be conscious, always, that we try to do our best and be as respectful as possible and be as conscientious as we can so that when we are publishing from the various communities, we are working with them and working for their work the best way possible. Paying attention is a lot of what we do, and people bring things to our attention and so, I’m not worried. I’m looking forward to two and three years from now because I think we’re going to have great lists that represent our lives at that time.

DC:

Given the issues you faced recently with the Susanna Moodie book, as a publisher, how do you present history in a way that informs but doesn’t stir controversy?

MW:

I don’t think that you can. What disturbed me [about the Moodie situation] was that a child was hurt, a student was hurt by what was presented. What we will be doing moving forward is that with any book that has Indigenous content in it, we are going to have an Indigenous consultant go over it. I still don’t believe there is one perfect answer. I think even within the community there are probably debates and issues and that kind of thing. I can only, I know this sounds perhaps simple, do my best to create the best and most respectful literature that we can provide. And be very conscious and thoughtful of what we are doing and that’s how we’re moving forward, really, with everything. Trying to make as few mistakes as we can.

DC:

And you’re going to keep going.

MW:

Yes! There are so many wonderful stories, how could we not? It’s our niche, we are no longer alternative, but we have our niche in the mainstream. I think that there are other wonderful Canadian publishers who have done some great books in all of the areas that we’ve been discussing… but that’s all we do. And that’s fine. I’m very happy about what other people do as long as they’re good books, and I’m very happy for them when those books succeed. But some of those books are not for me, and not for Second Story. And I’m good with all of that.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Dory Cerny is a writer and editor living in Toronto. Before her recent return to the freelance life, she was the Books for Young People editor at Quill & Quire for six years. In addition to writing about the Canadian book scene and reviewing fiction, non-fiction, and kidlit for Q&Q, Dory also contributes book-related writing to The Humber Literary Review, The Hamilton Review of Books, Canadian Children’s Book News, and CBC.ca.