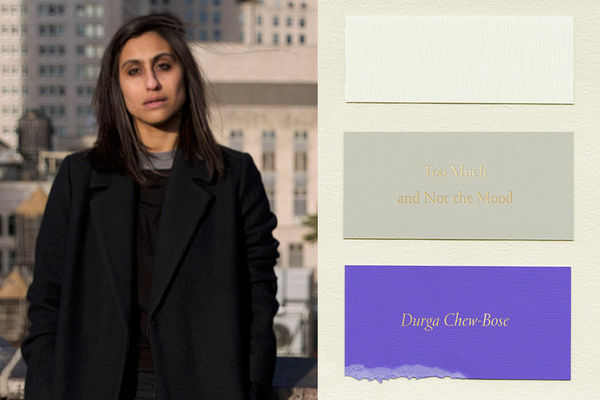

Making Time: Blueprinting, or How Durga Chew-Bose Showed Me the Kinship Between Music and Writing

By Shazia Hafiz Ramji

On the first day of social distancing due to COVID-19, I woke up with my synthesizer beside me. I sat up in bed and stabbed some keys for an hour, fed it into my laptop, put it all aside, and returned to the daily hustle of work.

That morning it struck me that the act of making and recording a melody was effortless. I never once stumbled with self-doubt, a fear of what other people might think, or whether it was any good. It was just me bumbling on the keys and saving it for later, so that I could build another layer, add another instrument.

Why is it so hard to do the same with writing? Why do I hear the voice, see the sentence in my mind, then stumble and pick up another word instead? Why can’t it be the same as when I play music? A melody rises in my mind and I press some plastic to approximate its sound, feeling no hesitation to record it. When I return to my synth in the evening, there is a melody from the morning. Over time, the melody draws itself to a beat, ensnares itself in a rhythm, calls for another instrument. Slowly, layer by layer, the drums, effects, voice, begin to stack on top of one another, congeal into song.

Music and writing are kin. People say this often. Why? Aside from technical analogies that juxtapose characters with moody chords, or plot structures with musical arrangements, music and writing are intuitively similar. They grow from pattern. They both begin when blueprints are activated.

Blueprinting

Blueprints are an architect’s language; drawings and sketches of floor plans and site maps. They are the foundation of what is to be built. They are model and microcosm, not merely representations but applicable maps with real consequences.

In her essay, “Since Living Alone,” Durga Chew-Bose uses “blueprinting” as a verb. It blew my mind:

“’When you travel,’ writes Elizabeth Hardwick in Sleepless Nights, your first discovery is that you do not exist.’ This sentence, which I read in late September as I shuffled and flopped from my couch to my bed and then back to my couch again, chasing patches of shade as the sun cast a geometry of light on the walls, this sentence surfaced on the page like a secret I’d been hurtling toward all summer but, until now, was nothing more than a half-formed figment. (I’ve come to hope for these patterns that build in increments, eventually sweetening into an idea I’ve long been blueprinting in my mind; I’ve come to understand them as a huge chunk of what writing involves.)

Blueprinting is an unconscious activity. It’s as if Chew-Bose had known Hardwick’s epiphany before she was able to give it voice herself. Blueprinting involves a gradual accretion of pattern. It is the incremental activity of the mind, like the blooming of an obsession. It precedes the recognition of a pattern but forms the smallest foundational unit of pattern.

When I wake up and make a melody, it is often only a few notes long, lasting anywhere from 10-20 seconds. The melody is blueprinting (not the noun, “blueprint”). It is a seed that grew out of play and feeling. It is nowhere near a song. When I return to it later, I pick up on the same notes. They are contagious (like COVID-19) and ask to be repeated. That repetition demands other instruments, so that the melody becomes varied and manifests itself in other voices, gathering other textures and beats around it, eventually becoming a song.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

When writing poems, I understand the relationship between music and writing on the level of sound. For example, the word “sentinel” recalls the word “brand.” There is a resonance between those words based on sound (a deep “n” sound and a soft “d” sound in your mouth and your head). However, I’m not aware of what those words might mean together. Aural association is old and primal knowledge. Babies learn to articulate the sounds of words first – before they know what they mean.

As I work towards yet another draft of my novel, I am taking cues from the musicians and poets, and from Durga Chew-Bose. I know that plotting doesn’t work for me and that I have to return to my unconscious and my intuition to write this draft.

Blueprinting is an activity that honours the incremental shifts which give way to a pattern – it honours the role of the unconscious in the sweeping analytical structure of plot that is to emerge. It gives a name to that place we rarely learn to inhabit as part of the writing process. It returns our work to a primal place, where music and writing begin together, with sound and feeling.

And so, I give voice to the imperfect fragments, the messy instinctive sentences, the surprising actions that characters make, the strange words surfacing, because I am learning to listen to myself – again.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Shazia Hafiz Ramji’s fiction was shortlisted for the Malahat Review’s 2022 Open Season Awards. Her poetry was shortlisted for the 2021 National Magazine Awards and the 2021 Mitchell Prize for Faith and Poetry. Shazia’s award-winning first book is Port of Being. She lives in Vancouver and Calgary, where she is at work on a novel.