On Pseudoscience, Wrestling, and Finding Storytelling in the Unconventional

By Alicia Elliott

When I was in university I had to take a science course to complete my undergraduate degree. I decided on “Science and Pseudoscience” – mostly because the title reminded me of the sort of conspiracy theories I’d hear on the Coast to Coast AM radio show my parents put on on long, late-night drives. Plus I wouldn’t have to use math, memorize formulas or be anywhere near chemicals I’d more than likely spill all over myself.

The class examined contested or debunked forms of science – such as phrenology or the claim that Vitamin C could cure cancer – in an attempt to determine what counted as science and, more importantly, why. If this all sounds more like sociology than science, that’s because it probably was. What really set this class apart, though, was the way my professor delivered his lectures: it was pure storytelling. He'd lay out for us the various groups in these scientific debates, what their vested social interests were, what they had to lose, what they had to gain, whether there was money backing certain scientists that could sway their findings. Every lecture was like a science-based thriller that ended with one side of the fight being deemed "good science" and the other "pseudoscience." I'd never realized science could be so damn exciting and dramatic.

Any time I tried to explain to other people what was so great about the class, they didn’t get it. I don’t blame them. I couldn’t really explain what I loved about it so much. It’s only now that I can properly put it into words. I loved that class because I’m a writer. I always appreciate a good story, and that professor made every lesson into an exceptional story. When I think about the way he laid out both sides of every debate, giving us just enough back story to see each perspective, I’m reminded how important it is in storytelling to show what’s at stake for all sides. I’m reminded that the best villains are complex, round characters with rich inner lives. I’m reminded how important it is to situate the reader in the context of a story’s world.

I didn’t learn this from an MFA program. I learned this from an undergraduate science class.

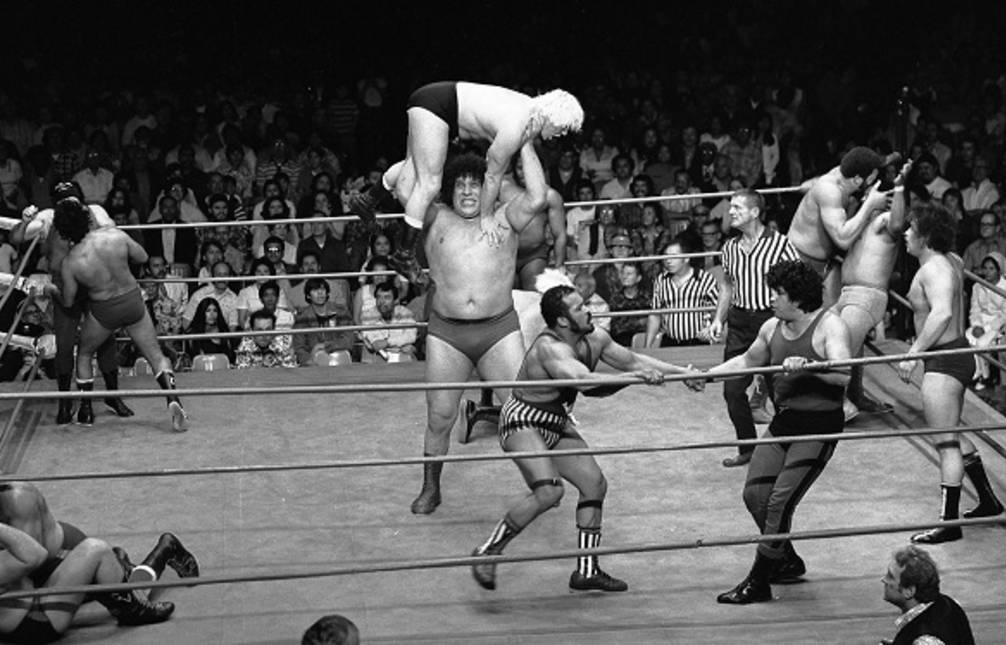

There are so many forms of storytelling that go unacknowledged and underappreciated simply because they don’t fit the bill of what we traditionally consider “a story.” For example, one of my favourite forms of storytelling is professional wrestling. This may sound ridiculous – after all, it’s professional wrestling. It’s one of the most ridiculous, campy hobbies one can have. But this campy, ridiculous hobby is entirely built around storytelling. Typically, a wrestling match will have a hero, or “face,” and a villain, or “heel.” The build up to the match will outline why the two are wrestling, strategically playing up key aspects of their respective characters to get a reaction. If the audience boos for the heel and cheers for the face, you know the story is being told right and told well. If they aren’t reacting at all, you know there’s a problem.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

When I watch wrestling, I like to analyze what’s working, what’s not and why. If it’s especially bad storytelling, I like to mentally rewrite the story, determining what changes they could have made to make it work better. In other words, I edit their story.

While this is incredibly nerdy and in no way academic, I honestly believe it has made me a better writer. By noticing and acknowledging the storytelling that surrounds us – analyzing not only why these stories impact us emotionally, but how they impact us emotionally – we can all become more sensitive to what makes a story work. And when we take different, exciting, unconventional forms of storytelling and apply them to our craft, we can, in turn, create different, exciting, unconventional stories.

There are plenty of things that we’re exposed to in our everyday lives that try to tell us stories. The way bodies move together and apart during a dance, for example, or an animal’s migratory patterns, or the process of diagnosing a disease, or some particularly juicy celebrity gossip. All this material surrounds us, constantly. What story is it telling? How can you use that story to learn about character, or plot, or tension, or how to effectively reveal information to the reader?

You don’t always have to look in a book to figure out how to tell a good story. There are other tools around us. We just have to use them.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Alicia Elliott is a Tuscarora writer living in Brantford, Ontario with her husband and daughter. Her literary writing has been published by The Malahat Review, Room, Grain and The New Quarterly, and her current events editorials have been published by CBC, Globe and Mail, Maclean's and Maisonneuve. She's currently Associate Nonfiction Editor at Little Fiction | Big Truths, and a consulting editor with The New Quarterly. Most recently, her essay, "A Mind Spread Out on the Ground" won a National Magazine Award.