On Re-Fusing CanLit--Or Why We Need Integrity, Community, and Roses

By A.H. Reaume

In a lot of the trauma memoirs I’ve been reading lately, I see the same metaphor used to describe the process of healing. You’ve likely heard it too. It compares healing from trauma to the Japanese art of Kintsugi, a method of repairing broken pottery with gold.

There is something poetic about the idea that we can put ourselves back together after trauma breaks us and that those broken parts might even be more beautiful once they’re made whole.

But I’ve never liked that metaphor.

One of the clearest lessons I’ve learned from trauma is that you cannot return to ‘before.’ Trauma reshapes you. It changes your very architecture. And it also shows you the places where you need to grow. To try to recreate yourself in the shape you once were – even bound by the beauty of gold - shouldn’t be your goal after a rupture.

I’ve been thinking a lot about CanLit and its ruptures lately.

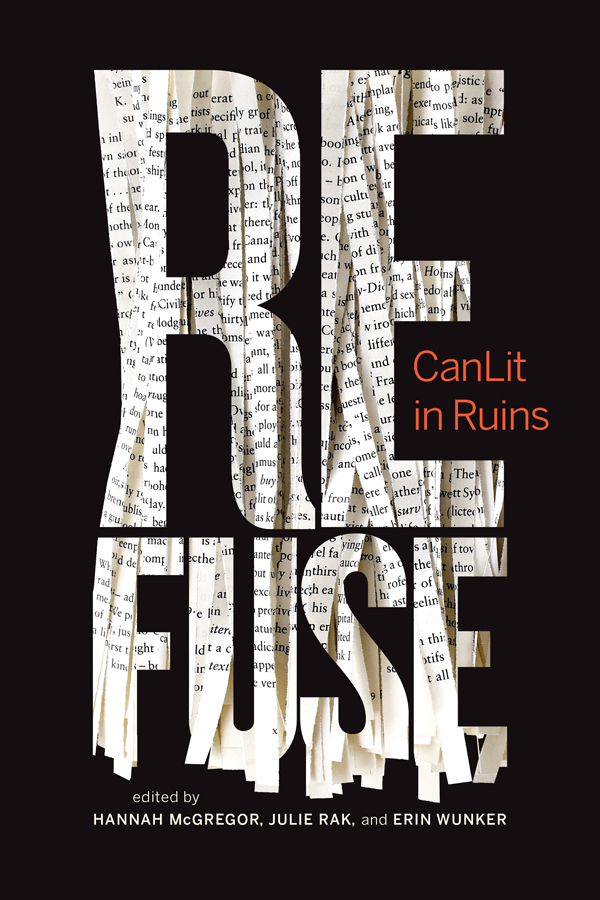

This was sparked by reading Refuse: CanLit in Ruins, a brilliant collection of essays, poetry, and prose from 24 writers (spoiler alert: I’m one of them) edited by Hannah McGregor, Julie Rak, and Erin Wunker that examines what CanLit is and what it could be in the wake of ruptures like the Galloway case, the Appropriation Prize, and a myriad of other issues that have surfaced in the last two years.

But the book is also about CanLit’s long history of ruptures. The way it has systematically excluded and marginalized BIPOC writers, queer writers, and disabled writers and covered over the rupture moments where those same marginalized writers pushed back – like when Lee Maracle took over the stage at the Vancouver Writers Festival in 1988 to protest the lack of Indigenous writers invited and to read from her book. Or the 1994 Writing Through Race conference and the backlash against it from some white writers.

What is a rupture? It isn’t just a moment when something changes. According to Refuse’s editors, “A rupture event is an event that interrupts the status quo. A rupture event does not irrevocably rend the fabric of what is, but it does make clear what has been. A rupture event is political in the sense that… it makes what was unseen visible.”

Look closely at the broken pieces after a rupture and it is possible to see more clearly the nature of the thing that was broken—to see, perhaps, that its flaw was in its design. That there might be a better thing to do with the pieces than just put them back together again in the same way they once were.

Refuse’s introduction, written collaboratively by its editors, considers three meanings for its title. ‘Refuse’ meaning garbage or waste, ‘refuse’ meaning to say no, and finally ‘re-fuse’ meaning, “to put together what has been torn apart, evoking the idea that, after something is destroyed, something better can take its place.”

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

It should be clear to anyone that’s paying attention that CanLit does not need to be painstakingly reassembled like an ancient ceramic bowl – with gold striations between its cracks to make them beautiful. That’s the old ‘add diversity and stir’ multicultural model that ignored structural issues and created ‘change’ by placing a cherry and diversity sprinkles precariously on top of the same old bland vanilla sundae that was CanLit.

In other words, we don’t need gatekeepers to let through a few more diverse writers and we don’t need to create better whisper networks – we need to shift where power lies in CanLit and how it operates. We need to change whose voices are boosted and what those voices are allowed to say.

We need to do what Kai Cheng Thom calls for in her poem titled ‘refuse: a trans girl writer’s story’:

I want to imagine a time and place into being

That is more than ‘CanLit’

Ever could be

Something wilder, freer

Than what is allowed to exist

In creative writing departments

And polite literary conferences

I want to know what grows

In the places where we bury the bones

So, what should we do with the broken pieces if we want to build something new, to re-fuse the writing community in Canada? What should we do if we want to create something different – something that doesn’t just reassemble old pieces but also adds new pieces to that mix and forms everything together into an entirely different shape? In other words, what if we want to create a literature that pushes against the nationalistic project inherent in CanLit’s creation? A literature that unearths the bones that both Canada and CanLit has buried?

For anyone truly interested in such a project (especially those who have more privilege), it is critical that they hold with the shattered pieces of CanLit. That they feel their sharp edges, trace the ways in which those edges have done harm. That they allow those jagged pieces to make them bleed a little. That they then work with all those who have been marginalized by CanLit to help reassemble the fragments into something different.

Refuse gestures towards this process as necessary for change in its introduction citing Donna Haraway’s maxim to “stay with the trouble.”

“For Haraway, there really isn’t an option of checking out of the trouble that is our current global and environmental state,” the editors say, “and so she advocates for alternative modes of conceiving of and making kin in order to thrive. She asks us to stay with the trouble rather than pretend it isn’t there or think that somehow we can just go back to how things were.”

I think that finding alternative modes of conceiving of and making kin is critical. The path behind us was one of pain. The path forwards looks like one of pain, too. There will be no quick revolutionary changes in CanLit--which the editors of Refuse acknowledge is at once an industry, a cultural field, and an academic discipline. But it’s also more than that. CanLit is first and foremost a community. And the ways in which CanLit has arranged itself in the past have been reflected by and reinforced by the nature of that community. By who was deemed a part of it and who was excluded. By who was invited to which parties. By who was published by which houses. By who was omitted from which writer’s festivals.

There is value in creating new forms of community. After all, there is a reason why the seeds of social change are often ‘community’ organizing. The ways we build kinship matter.

Creating kinship with another writer is a declaration that they are valuable, that their voice is important. What I see around me are writers from different backgrounds reaching across their communities and differences and rearranging themselves -- reaching out, mentoring, offering support, meeting up for coffee, tweeting at each other, blurbing each other’s books, investing in each other’s success. This matters. It matters because it is making space for writers who are typically excluded or marginalized. It is creating a new invite list to the party. In fact, it is hosting a different party altogether. This is a key part of rebuilding amidst the ruins. This is activism in its quietest, but also most personal and heartfelt sense.

But this kinship is also what’s needed as a basis from which to work for broader structural change. If you build a house by stacking one brick directly on top of another, you can easily push down those individual columns of bricks. But if you build a house by staggering the bricks, by enmeshing them between each other – they bear more pressure. They sustain each other. They work together to resist the force that is trying to knock them down.

And that’s important. Because those pushing for change to any status quo will inevitably face backlash and no matter how sturdy they are alone, they will crumble without the support of others.

Many writers are currently mired in fighting the defamation lawsuit that Steven Galloway launched against them. They are stressed out and worried and trying to navigate a complex civil justice system that likes to draw things out for years and rack up lawyers bills.

But while this lawsuit is a terrible thing, the response to it by many in the CanLit community can only be called beautiful. That’s the only word that comes to mind when I think of how the donations rolled in when writer Amanda Leduc launched a GoFundMe campaign in support of the Galloway defendants.

As I watched a seemingly endless scrolls of names cross my screen as donations quickly went over $25,000 and then $50,000 in the first day, I imagined each of the donors holding a broken piece of what CanLit was and fitting that piece into some new shape with each donation.

I couldn’t yet see what that shape would become because it wasn’t finished, in fact, it won’t be done for years, but I knew that something was being re-fused. Something beautiful was being made at the site of the ruptures.

That beauty is in 18-year-old writer Isabella Wang who gave $1,000 to the fund. It’s in the work of Rahim Ladha, a dancer and fundraiser who is struggling with major health issues, yet is working to put together Soar, a fundraiser in February for defendants. It was also in the room as Amanda Leduc, Rahim, Carrianne Leung, and myself met up at a coffee shop in November to strategize about how we would raise more money and how to distribute the funds.

As of now, there is more than $70,000 raised from over 900 donors. Many of those donors also helped me send care packages to the defendants filled with letters of support, notebooks, books, and snacks.

“I felt less alone,” I have been told by defendants who received them. “I will always be grateful,” others have said. “I am overwhelmed. I am overwhelmed. I am overwhelmed.”

What is the measure of human kindness against the weight of CanLit’s ruptures? I suspect that it is both everything and not nearly enough.

And herein lies the problem. We can reshape CanLit by donating to a defence fund or organizing against racist comments in creative writing workshops, or speaking back to ableism at writing festivals, but the total costs of the lawsuit will be much more than we can raise ourselves and structural racism, ableism, and white fragility doesn’t easily go away. There is a cost that is being paid and some individuals and groups are paying it disproportionately.

So, what do we do in the face of the ways in which our efforts are undermined? Or the ways in which even the strength of community falls short of creating the change necessary immediately? It would be easy to feel like we should give up. Like we’re no match for the strength of forces that are bigger than ourselves.

But I’ve been reading a lot of Rebecca Solnit lately and I’ve found solace in her words. One thing that she talks about is how important it is for us to act with integrity, even when others aren’t doing so around you.

“Often it’s an example of passionate idealism that converts others,” she says in her book Call Them by Their True Names. “The performance of integrity is more influential than that of compromise. Sometimes, rather than meeting people where they are, you can locate yourself someplace they will eventually want to be.”

There are many amazing people in CanLit who are doing just that and inspiring others to keep pushing.

“I’ve built a career based on integrity and honesty instead of fake ass-kissing,” said Alicia Elliott in a recent profile in Flare.

Elliott has been an inspiration for me and so have Gwen Benaway, Yilin Wang, Jael Richardson, Amanda Leduc, Lawrence Hill, Carrianne Leung, and Daniel Heath Justice. It is the passionate activist work that these writers do that motivates me to keep doing the work myself. To keep pushing for change.

Solnit emphasizes in her book that when we act with integrity our actions aren’t worthless if they don’t end up immediately giving us the result that we want.

In my piece in Refuse, ‘In The ‘New CanLit,’ We Must All Be Antigones,’ I talk about the violence of vague ‘hope’ when it’s used as an excuse to for some to not do the work to make things better because they want to believe that change will come without them having to work for it. But I think that a certain kind of hope is necessary to keep doing the work. It’s a hope that recognizes that as much as we want and need change to happen immediately and to be revolutionary in nature, change is often painfully slow and iterative and happens not over weeks or months, but over historic timescales.

“Newcomers often think that results are immediate or they’re non-existent,” writes Solnit, “that if you don’t succeed right away, you’ve failed. Such a framework makes many give up and go home just when the momentum is building and victories are within reach. This is a dangerous mistake I’ve seen over and over. To see where we are, you need a complex calculus of change instead of the simple arithmetic of short-term cause and effect.”

This complex calculus of change is one that is particularly hitting home for me recently. When I was in my early 20s, I was actively involved in efforts to get more young women involved in feminism, politics, and leadership. Now that I’m in my mid-30s, I’m seeing many of the young women who I helped, encouraged, and provided resources to start taking on leadership roles.

One friend recently ran for office and told me that it was my example over ten years ago that made her get involved in the first place. It was her first election and she narrowly lost, but she is in her early 30s. She has decades left to run again and make a significant difference in political life.

My old roommate from undergrad also just messaged me the other day to tell me that the feminist work that I did changed her life and has made her actively push for greater equality in the field of Marine Biology for the last decade.

It took me over ten years to see the results of my work and influence in just these two people’s lives.

What it’s shown me is that we can never truly understand the scope of our actions in the moment. Even ten years later, the impact of what we do can be uncertain. What’s important is that we do the work and we keep doing the work. That we try to live and act with integrity, love, justice, and kindness. That we endeavor to do so better even if we mess up and have to apologize or recalibrate our work. That we do it when no one is watching and that we do it when everyone is.

Because we have to keep picking up the pieces of CanLit and fusing them together in a better, more just, and more beautiful way. We need to do it even in the darkness cast by the shadow of the ruins. We have to do that every day and week and month and year and trust and hope that something new will be created.

As Solnit writes, “I began talking about hope in 2003… 15 years later I still use the term because it navigates a way forward between the false certainties of optimism and pessimism and the complacency or passivity that goes with both.”

“Optimism assumes everything will go well without our efforts,” she continues. “Pessimism assumes it’s all irredeemable. Both let us stay home and do nothing. Hope for me has meant a sense that the future is unpredictable and that we don’t actually know what will happen but that we may be able to write it ourselves. Hope is a belief that what we do might matter. An understanding that the future is not yet written.”

That is the message that I took away from Refuse, that re-fusing what was CanLit into something new might be possible.

In the powerful words of Alicia Elliott in her piece ‘CanLit is a Raging Dumpster Fire,’ which is featured in Refuse, “We can’t just stand around and complain about the dumpster fire in front of us forever. Eventually, we have to grab some fucking fire extinguishers and put that fire out. In other words, we have to sit down, assess the criticism, and do the work to fix the problems. We don’t need to wait for stubborn, lagging institutions to change. We never have. We can make change ourselves, now.”

And, we are making that change.

But it’s important to remember that change happens slowly and it can sometimes feel like we’re getting nowhere. And while we’re waiting for change people are still harmed – whether through a lawsuit or an appropriative story that a BIPOC writer has to do the labour to call out. That’s the drawback to Solnit’s vision of hope and to the traditional way we understand social change. We focus our limited resources so narrowly on the struggle for progress that we don’t spend enough time assessing the current ruins and caring for the wounded. We need to do that too.

The people being sued need bread (or money), I told a friend who asked why I wanted to make care packages for the Galloway defendants, but they also need roses. That ethic of community care was taught to me by the people who cared for me when I experienced a disabling head injury in 2017. By people who brought me food and flowers and friendship when I couldn’t leave my house for many months. It didn’t heal me or take away my pain – but it was those ‘roses’ that kept me going. The kinship they represented that sustained me through the struggle.

So, let us keep living with integrity, keep working for change in the darkness, and keep hoping that one day the light will come. But let us also remember to give each other roses and to let the ethics of community and care be part of what re-fuses our writing landscape in Canada.

If we do that, we are already living in some ways in that future we’re working towards. We are already living in something that is different than CanLit, that is greater, in someplace that doesn’t ignore the bones but acknowledges and honours them.

And every day, if we each pick up just one broken piece and fit it into a new configuration, I hope we will be able to step back someday and wonder together at the beauty of what we made.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

A.H. Reaume is a Vancouver-based fiction writer who reads too much and is currently in too many book clubs (four in total). Reaume has a background in feminist activism and an M.A. in Canadian Literature from UBC. She's been published in the Vancouver Sun, The Globe and Mail, USAToday.com, and Time.com and is currently trying to finish her first novel.