On writing politically, or how not to make your fiction sound like a lecture

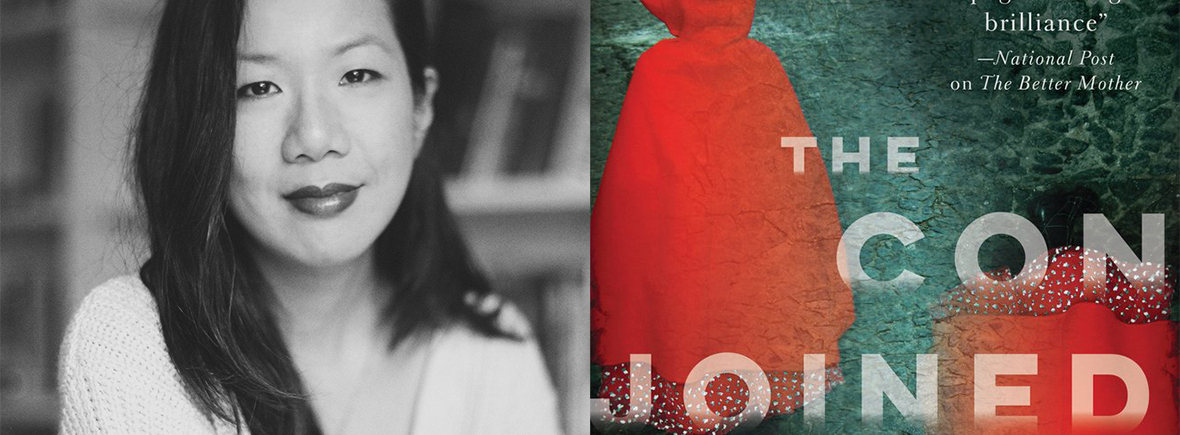

By Jen Sookfong Lee

When I started writing my most recent novel, The Conjoined, I began with the idea of subverting classic crime fiction, something that I thought would be a fun bookish game. What if I could write a literary crime novel, one with an unexpected protagonist and that plays with the tropes of victim and villain? I began by making all the principal characters women—the investigator, the victims, the suspects. The family at the heart of the story is Chinese Canadian, people who struggle with poverty and cultural barriers, who are the antithesis of the model minority stereotype. And then, as the novel developed, I focused the narrative on the lives of the girls who had died, rather than the focusing on the men who had hurt them. In the end, the novel that was supposed to be fun, grew into a novel about white feminism, immigration, and survivor narratives. And if you’re wondering, yes, I am a lot of fun at cocktail parties!

I’m not really a political essayist (this column notwithstanding) and politics have never driven my fiction. And yet, when the final draft is done, I see exactly how political my novels are. My initial ideas are never based in politics but are, instead, always a series of questions. What if I wrote a literary crime novel? What might have happened between the residents of Vancouver’s Chinatown and the burlesque dancers who worked at the cabarets nearby? How would it feel to be haunted by your family’s immigrant past? The questions are not inherently political, but the answers, which are the final stories, always are.

New writers often ask me this: how can I integrate my politics with my fiction? For a while, I didn’t know how to answer because the politics that appear in my novels were never placed there for political reasons. I made decisions that made sense for my characters, that grew out of time and place. If my protagonist is a white social worker who feels uneasy with how the child welfare system manages the lives of families of colour, then every decision I make for her will be political, whether I like it or not, even if I’m not trying. But this isn’t much of an answer.

Here’s the thing: when writing fiction, we’re world building, no matter the genre. Readers come to our books to experience our worlds, whether they’re dystopias or set in New Brunswick or inside a house in an unnamed suburb. Our job as fiction writers is to deliver on this world and its inhabitants. The readers need to believe that this story could really happen, in this setting, with these characters.

So, it follows that our choices should always serve the story. But it also follows that no story is without political content. Even the fluffiest beach read contains interactions between men and women, bosses and employees, the collision of people from different communities. If you write about people who live in a place, politics are inevitable.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

After three novels and eleven years of fiction writing, I finally have an answer for how politics and fiction can come together. We don’t have to try to make our fiction political. It will be regardless. And if we care about politics, then those politics will find their way into our writing, in the same way that any of our preoccupations show up in our stories, both unwittingly and not. Going through a divorce? So is your protagonist! Angry at a personal nemesis? That jerk in your novel sure looks familiar!

Sometimes the premise of a story is visibly political. In The Conjoined, two teenaged girls from Vancouver’s troubled Downtown Eastside go missing and the social workers and police write them off as runaways, never really investigating, while their immigrant parents are buried under grief, uncertainty, and barriers to accessing help. The politics here are obvious. And yet, the characters still dance whenever “Karma Chameleon” plays on the radio. A grandmother falls asleep every night in a big, shabby armchair. A woman leaves her boyfriend because she craves emptiness and silence. These are the specific, idiosyncratic details readers stay for and connect to. These decisions are the foundation of what fiction is: an immersive experience that readers crave so they feel or think or escape.

So really, if you build the best possible story, the politics will come. No matter what.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Jen Sookfong Lee was born and raised in Vancouver’s East Side, and she now lives with her son in North Burnaby. Her books include The Conjoined, nominated for International Dublin Literary Award and a finalist for the Ethel Wilson Fiction Prize, The Better Mother, a finalist for the City of Vancouver Book Award, The End of East, The Shadow List, and Finding Home. Jen acquires and edits for ECW Press and co-hosts the literary podcast, Can’t Lit.