Painting a Story: Danila Botha on Writing and Painting

By Danila Botha

Since I was a kid, I’ve always painted. I’ve painted through every age of my life, through every possible emotion. I’ve painted when I was ecstatic and needed to share the feeling, I’ve painted through anger, disappointment, and anxiety. I’ve painted to process things. At times it’s felt, and sometimes still feels like my hand, or my black pen, or paintbrush have a life of their own, and they’re telling me what to paint. Sometimes I have a plan, and I go into a piece with an idea, and sketches and colours carefully picked out, but often, I don’t know what I’m doing until my hand tells me what’s on my mind and in my heart. It’s a freedom that I try to translate into my writing. A few of what I think are my best short stories have come out of trying out a similar process- starting out with one image, or setting or character, building, and adding and enjoying every step of the process.

I enjoy painting so much. I marvel at how time disappears, how intense my focus is, and yet, how much fun I’m having.

Some of my early memories involve figuring out which cleaning products removed paint and marker from my bedroom floor (which incidentally was white and showed everything) I was lucky to do an after-school program as a kid at an incredible place called the Art Foundation in Johannesburg. Inside, it looked a lot like 401 Richmond in Toronto, which is to say, it is a creative space, full of real artist studios, and real artists working all the time. As kids, we got to do whatever we wanted (I remember someone asking how paper was made once, so we learned how to make it) but we also got to watch artists as they sketched, watching them catch mistakes, and fix them without being precious about it, or hard on themselves. We learned how to love the whole process.

Not only is the process of painting and writing similar for me, the two are inextricably linked.

With art, my first draft is often a lot more simple- the shapes are there, but the colours and textures, which are my favourite part, and some of the sharper, more distinctive lines are missing.

With writing, my first drafts often look like a lot of feelings and thoughts and absolutely no setting or location whatsoever. It’s as if my characters, if you can call them that at this stage, are all heads and hearts with no bodies.

Art has always been an essential part of me learning how to embody my characters, to slow my pacing and remind myself of where the characters are in the moment, and where they’re going.

My original draft of the title story in my new collection, Things that Cause Inappropriate Happiness was little more than my slightly fictionalized thoughts on having a chronic illness. I have Rheumatoid Arthritis, and once I discovered that a side effect of taking Prednisone, which I unfortunately sometimes have to take, is inappropriate happiness, I knew I had to write about it, because it was so bizarre. How would a person determine how much happiness is appropriate or inappropriate anyway? I enjoyed getting to describe the specifics of what the condition was like, in every way.

My main problem was it didn’t really feel like a short story.

In my second draft, I kept thinking back to a surreal real life moment I had in Gwartzman’s art store in downtown Toronto a few years ago. A customer who looked a lot like Leonard Cohen, with a radiant, otherworldly smile started chatting with me about painting and art.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

I pictured the art store, with its beautiful supplies, and pictured a reluctant art teacher bringing her class on a field trip

In the midst of her looking at paint, she encounters this same man.

The next trick was to make sure no one else witnessed what was happening. I took her down a rickety (imaginary) set of stairs into the basement, where they sell things that are extra discounted.

There she finds this man sitting on a couch.

I really feared for my ability to pull off my next idea: I wanted him to look like Leonard Cohen, but be a conduit for travelling back to her teenage years when she originally conceived of being an artist.

This is how this part of the final version of the short story turned out, after I sketched a lot:

An older man in a charcoal grey suit, with a black fedora sat on a couch in the corner.

He had olive skin, a roman nose, and intense half moon shaped brown eyes framed by thick eyebrows.

“It’s nice to see you, Lielle.”

“How do you know my name?”

He raised an eyebrow. “I know a lot of things.”

The door was closed, but the windows were open.

“You may have heard of people like me. Some of us specialize in the past. You seem to be struggling. Would you like to go back? I can take you to when you were exactly their age, to 1998.”

I stared at him.

“What do you mean, take me?”

“You can sit down on this couch, right here,” he held his arm out, pointing to the black leather couch beside him.

My knees burned. I sat down.

“Do I have to do anything?”

He laughed. “No. Just have a seat.”

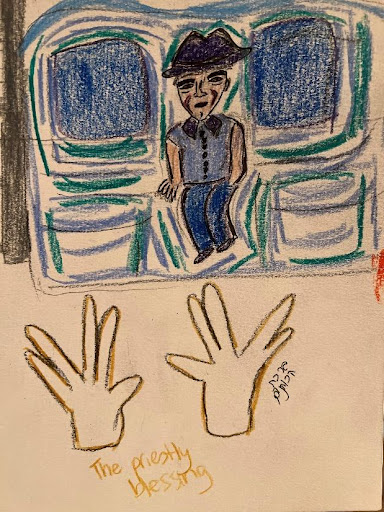

He waved his hands over me, his fingers separated like a Cohen before they start duchening. I wasn’t religious, but I’d always found it haunting when I heard it in a synagogue on high holidays. He told me to close my eyes, and I heard him chanting the Priestly blessing in Hebrew and in English.

May God Keep you and Bless you

May His Face Shine on You and Show you Favour

May He lift His Face to You and Bring you Peace

*

When I open my eyes I’m lying on my stomach. I roll onto my side and feel myself falling off a bed. I jump up, suddenly realizing that I can, and that it doesn’t hurt.

I stand on my tip toes. I jump up and down, lift my legs up high. I twirl like a demented ballerina until I see the clock radio on my bedside table.

6:15. Too early for anyone to be awake. My CD player stares back at me. I study the CDs on the table beside it: Tori Amos, Chumbawamba, a homemade mix which included Third Eye Blind, Aqua, Sugar Ray and Meredith Brooks, Jeff Buckley and Blur.

Sketching was an essential part of visualizing the details.

These are the stages of my Leonard Cohen painting, that I also made as I wrote each draft:

If you’re feeling stuck, if you have writer’s block and don’t know where to go next with a piece of writing, try to sketch it out. In the same way that you wouldn’t judge your first drafts of writing, don’t judge your sketches, just use them as a tool. It’s incredibly helpful—once you start, you won’t be able to stop.

This is the first instalment of a special guest series about authors who are prolific in other art forms, and how that work shapes their writing. The series was suggested by poet, educator, and visual artist Paul Vermeersch! Keep an eye out for future columns from other talented polymaths in the writing community.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Danila Botha is the author of three short story collections, Got No Secrets, For All the Men (and Some of the Women I’ve Known) which was a finalist for the Trillium Book Award, The Vine Awards and the ReLit Award. Her new collection, Things that Cause Inappropriate Happiness will be published in March 2024 by Guernica Editions. She is also the author of the novel Much on the Inside, which was recently optioned for film. Her new novel, A Place for People Like Us will be published by Guernica in 2025. She teaches Creative Writing at University of Toronto’s SCS and is part of the faculty at Humber School for Writers. She is currently writing and illustrating her first graphic novel.