The Burden of Positivity

By Jael Richardson & Submitted by Kevin

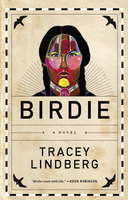

As a writer, reader and reality TV watcher, Canada Reads masterfully combines some of my favourite practices and past-times in a nation-wide, televised battle of the books. And while I enjoyed the 2016 debates – watching national celebrities compassionately defend great, Canadian stories – there was one comment by defender Farah Mohamed regarding Tracey Lindberg’s Birdie that irked me, and I’ve been wrestling with her words since March.

“I was really hoping that it would be a book that would not be like the stories we have heard,” she said. “I am so desperate to read a story about an Aboriginal woman that doesn’t necessarily go through all of this.”

The statement was made in regards to Lindberg’s main character, Birdie, who experiences sexual trauma and wrestles through mental health issues in the story. And while there is no question, that there are many voids in Canada’s literary canon – that there is a universal desperation for voices that are missing or absent – what bothered me about Mohamed’s statement was the way she assigned that responsibility to Lindberg, a not-so-subtle why-couldn’t-you-write-something-else implication, a cumbersome prescription that Birdie defender Bruce Poon Tip rightly alluded to as a way of colonizing Lindberg’s work.

This burden of positivity, is a tough one for writers – at least it is, for me.

When I began writing a novel, soon after publishing a memoir, I workshopped it with another writer. I had created my first book during a post-graduate program where I relied heavily on feedback. I wanted to recreate that collaborative environment.

In one of the early chapters of my novel, my protagonist – a woman of colour – stares into a mirror, examining her head, her hair, her face. My writing friend said, “I hope she’s not going to have those identity questions. It would be nice to see a black female character who is happy with herself and doesn’t take on those negative ways of looking.”

I spent months re-working the story, re-starting it, re-thinking my protagonist. I needed a new beginning or a new way of seeing the world that would avoid this cliché. But nothing came to me. And for a long time, I thought that made me a failure. If a man of colour was tired of reading about women of colour wrestling with concepts of beauty, perhaps other readers were as well. Perhaps my writing was one big cliché. Perhaps I was a failure. Maybe both.

I came to the conclusion, eventually, that I can’t write his story. I can’t write the story he wants to read or even the story readers want to encounter. I can only write the story I’ve got – which is what I wanted to say to Farah Mohamed in my own defense of Tracey Lindberg’s complicated character Birdie.

Birdie is the story Lindberg was given. And it’s a gift from her to all of us.

It is not a happy story per se. But these are not happy times for Indigenous women in Canada. These are hard and complicated times, tragic, even. Urgent. And as a reader, I think it’s more important for me to wrestle with that truth by considering Lindberg’s story in the exact way she tells it – particularly given that Birdie is one of the far-too-few Canadian stories by and about Indigenous Canadian women published by a multi-national publishing house.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

While some authors can and should write fantastic worlds or true to life settings where positivity abounds and happiness is abundant, other writers are called to wade through the murky waters of difficult experiences using painful prose to shed light where dark and difficult times prevail, unencumbered by the stories that have come before them.

In life, marginalized people continue to face oppression and injustice, and there are many readers (well-read and reluctant) who do not know or understand the particularly weighted life of systemic oppression or marginalized experiences, who have not absorbed or heard “all of the stories” that have left Mohamed and my writing friend feeling so desperate for something different – a desperation, I would argue, that is far more relevant for Canadian publishers to wrestle with than any Canadian author.

“Birdie is an important book that makes us ask what is my responsibility as a relative to indigenous people? An indigenous woman has … been captured and put on the page by another indigenous woman. No holds barred. Bruises and all. And it’s beautiful.” – Bruce Poon Tip, Canada Reads

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Jael Richardson is the author of The Stone Thrower: A Daughter's Lessons, a Father's Life, a memoir based on her relationship with her father, CFL quarterback Chuck Ealey. The book received a CBC Bookie Award and earned Richardson an Acclaim Award and a My People Award as an Emerging Artist. A children's book called The Stone Thrower came out with Groundwood Books in 2016. Her essay "Conception" is part of Room's first Women of Colour edition, and excerpts from her first play, my upside down black face, are published in the anthology T-Dot Griots: An Anthology of Toronto's Black Storytellers. Richardson has an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Guelph, and she lives in Brampton, Ontario where she serves as the Artistic Director for the Festival of Literary Diversity (The FOLD).