The challenges (and joys) of receiving feedback

By Lindsay Zier-Vogel

I am not proud of it, but my initial response to feedback on my writing is an instant NOPE. No way! ABSOLUTELY NOT.

“What if you switched the point of view to third person?”

NOPE. No way! ABSOLUTELY NOT.

“Try taking out the epilogue.”

NOPE. No way! ABSOLUTELY NOT.

“You might consider writing letters from Amelia Earhart to help the reader feel connected to her story.”

NOPE. No way! ABSOLUTELY NOT.*

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

It doesn’t matter if it’s from my writing group, my agent, or my editor, I have an immediate across-the-board rejection of all major feedback. Outwardly, I murmur and nod and look like I’m contemplating it when I’m rejecting it vehemently. It’s become comical (to me) how intense and clear this initial reaction is.

But then I take a walk, or go for a swim, or have a shower, and after allowing the feedback to percolate for a day or two, I can actually be figure out if the potential changes work for me or not.

I felt less alone in my initial reaction after chatting with Jen Sookfong Lee, who gives feedback as an acquiring editor at ECW Press, and receives it as a poet, novelist, children’s book writer, and essayist. “My immediate reaction is usually irritation,” she says with a laugh. “We always want everything to be perfect right away but that never happens.

“If it’s a book, it takes me at least a couple weeks to get my head around it. If it’s something shorter, it usually doesn’t take me that long. There have been occasions when I’ve received feedback that is really inspiring right away and that’s when you know it’s magic, and they’ve put their finger on exactly the thing that you already knew deep down was wrong.”

As I wait for feedback on my own work-in-progress, I decided to do a deep dive on how other writers integrate feedback into their work.

J.J. Dupuis, author of the Creature X Mystery series, published by Dundurn Press, reminded me that my own headspace can change my reaction to feedback on my work. “My feelings toward the work-in-progress heavily affect how I take feedback,” he says. “If I’m feeling particular unhappy with the work, I tend to want to implement every possible change in hopes of making a better book. But if I’m feeling confident about the work, I take a little more time and try to have a measured response to any feedback. In the end it is the strength of the final product that matters.”

Sanna Wani, author of new collection of poetry My Grief, The Sun, out with House of Anansi Press in April 2022, cautions that timing when receiving feedback can really shape and alter a piece: “I’ve found positive feedback does a world of good in [the early stages of writing] and sometimes well-meaning negative critique can kill a piece before it even has legs.

“My friends at Firefly Creative Writing taught me a lot about that—believing in the piece, in what its potential is.”

Lee says that finding the right person to get feedback from can be crucial. “I usually try to find someone who is really conversant in whatever genre I’m writing in. My biggest weakness in poems is line breaks and visual structure and lay out on a page, so I’m always looking to find feedback from poets who are really good at that. It makes a huge difference. That really matters to me.

“If I’m writing non-fiction, or memoir, finding people who are really good at that particular form is super important.”

Wani loved the editing process for her forthcoming poetry collection, that she undertook with editor, Kevin Connolly. “He helped me trust myself and was available, communicative and sensitive to my vision with the collection. Sometimes it was the whole engine of a poem we tinkered with together. Sometimes it was, Does this word work? Do you know another? A lot of editing is just listening.”

The best feedback Wani received during the process? “I trust you. Change this.”

When editing his most recent book, Umboi Island, out in March 2022, Dupuis says the best feedback he received was the permission to ignore certain characters. “I was trying too hard to incorporate each member of the ensemble cast, and that meant a lot of unnecessary scenes and dialogue. Once I was told that in real life, not everyone gets their time to shine in every moment, I became comfortable thinking, ‘Okay, you’re on the back burner in this book, but you had a pretty big role in the last one, so your turn is over, sit down.’”

Lee is deep into edits for her creative non-fiction pop culture memoir, Superfan, and says the best advice she received was from fellow writer, Alicia Elliot.

“She said to me: “If you’re feeling like you’re stuck, and you’re feeling like the essay is not revealing itself to you is to show your hand to the reader. Just be honest, say ‘I’m having a lot of difficulty writing this memory,’ or ‘This is feeling traumatic for me,’ or ‘This isn’t the way is happened, but it’s the way I wish it had happened.’ And she said, just being able to couch that and show your reader that you’re fallible or vulnerable is going to make the book better and it can open things up for you too.”

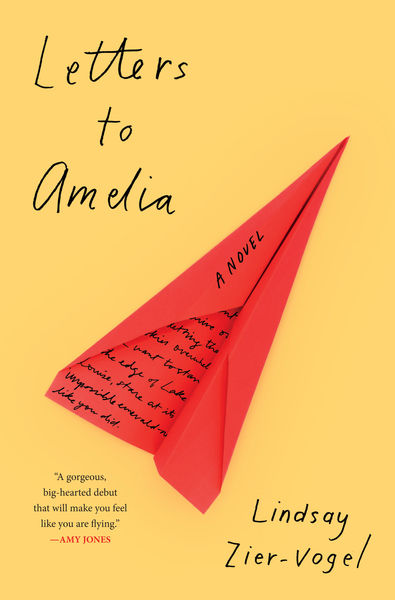

*Note: Eventually I took all of these suggestions when editing my novel, Letters to Amelia, and am SO GLAD I DID (even though I am still thinking about that epilogue).

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Lindsay Zier-Vogel is an author, arts educator, grant writer, and the creator of the internationally acclaimed Love Lettering Project. After studying contemporary dance, she received her MA in Creative Writing from the University of Toronto. She is the author of the acclaimed debut novel Letters to Amelia and her work has been published widely in Canada and the UK. Dear Street is Lindsay’s first picture book, and is a 2023 Junior Library Guild pick, a 2023 Canadian Children’s Book Centre book of the year, and has been nominated for a Forest of Reading Blue Spruce Award. Since 2001, she has been teaching creative writing workshops in schools and communities, and as the creator of the Love Lettering Project, Lindsay has asked people all over the world to write love letters to their communities and hide them for strangers to find, spreading place-based love.