When History and Fiction Collide: On the Necessity of Irreverence

By Shazia Hafiz Ramji

A week before I attended my first writing residency at the Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity last month, a historian in Vancouver gave me an envelope containing a strip of negatives. I developed them the same day: three photos of my mysterious maternal grandfather. In one photo, he is leaning over his tabla and harmonium, a hint of exhaustion on his face. In another, a close-up, he is looking into the upper left quadrant of the photo. His eyes are pale. He is wearing an impeccable linen suit. He looks troubled and angry. He looks colonial.

The historian had not told me what he wanted to give me, only that he would like to talk. I was not expecting to see photos of my mom’s dad, the man I’d never met, whose life has felt the closest to my own in the stories I’d heard of him. He was a Master of Music, as my mom says. A filmmaker. He kept to himself and didn’t go to mosque with the rest of the family. He was the one I’ve yearned to know since I was a child, the sensitive weirdo in the family. Hearing about him often made me feel less lonely.

My maternal grandpa is the reason my novel moved into historical fiction territory. I wanted to know him. If I could know him, I would know myself and my family. But there was so little to work with, so the complete historical storyline I wrote and took to Banff was based on my paternal grandparents.

One of the reasons I desperately wanted to attend the Autobiography and Fiction residency at Banff is because I felt a sense of responsibility to my family history. The stories of my great-grandparents and grandparents have allowed me to reconcile who I am now, with all my secrets and pasts in tow. In writing the stories of their lives, I’ve felt accepted in a vast and quiet way that I didn’t feel before I began research. I work to make myself a conduit; I believe in the truth of the world of my making and I allow my ancestors and the archives to guide my belief. I understand that history is a story too, that anyone’s truth is layered and uncontainable.

I had finished the contemporary storyline as well as the alternating historical storyline, but somewhere along the historical storyline, I became obsessed with “Truth”: if only I could access the archives in Greenwich … if only I could go to Bandar Abbas … if only I was still dating that sailor I would have access to a boat … I was too deep in history. I knew this because it had begun to feel wrong to make things up and I felt as though it could only be righted by the archives and research.

When August rolled around, I was ready to go to Banff to loosen the grip of the historical and allow the fictive to enter the novel again, to loosen the sense of responsibility I felt to the stories of my ancestors. This was the challenge I saw for myself: to allow the stories of my paternal grandparents to cross over into fiction from history, just like I’d been able to do with the contemporary storyline of the novel.

So, when I was gifted the photos of my maternal grandpa, the challenge felt insurmountable and new. I felt like I had betrayed the maternal side of my family, that I had been writing the wrong story, that these photos were a sign that I needed to refocus. To attempt a new historical storyline, I would have to shift from ships to trains, an entire century, and a different way of being – British colonizers very much present. That was for starters.

I cried, obviously. This was the first time I felt that something I’d written was a huge mistake.

I realized that there was no way I could rewrite an entire historical storyline based on my maternal grandpa, that I couldn’t simply forsake the one I had finished about my paternal grandparents – a storyline that was intricate and interdependent on the contemporary autofiction storyline.

I lowered my expectations out of self-preservation and so that I could have a good time at the residency. I told myself I would write a new short story. If I was in my apartment in Vancouver, I would have vaped and watched Blue Planet to clear my head. But I was in Banff, so I went to the hot tub.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

In the hot tub, two men were sitting beside each other staring at the glass ceiling. One of them wearing red shorts talked about how he felt the weight of the spirit on his chest one day at church. The other one wearing blue shorts kept shifting, positioning himself in front of the jets. I zoned out. Suddenly Blue Shorts said, “Have you gone for a check up?” He said it as if he was asking for the time. He seemed to be dismissing Red Shorts’ religious experiences. Red Shorts was quiet for a few seconds. Then he laughed and said, “it’s too much to deal with the heart.”

That hot tub session made me realize why I was so mired in history: I cared too much. I had to be like Blue Shorts. I had to be irreverent – to care less in the face of what’s sacred and untouchable.

I went back to my room and wrote a poem about a secretive colonial man with pale eyes. It’s a bad poem. I say “fuck you” in it twice.

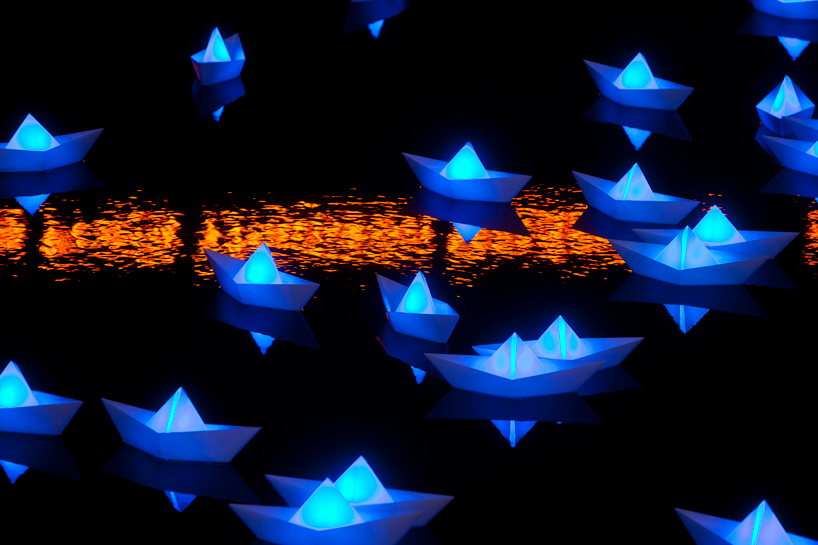

I began the new short story as a way of dodging the poem and dodging the novel. In the new story, my protagonist remembers making a paper boat with her maternal grandpa. They are sending the paper boat from an English shore to the coastal homeland of my paternal grandparents. This is fiction. I never met my maternal grandpa and the protagonist is basically me, but not quite.

Because of the immense responsibility I felt for the stories of my ancestors – and to history – I lost sight of the fact that being a conduit is a bit like being a compost pit: it’s one thing on top of another to make a new thing all joined up and messy. Not one thing separate from another with clear chapter headings separating time and space.

Novels are uncontainable, like the truths they hold, changing with each reader and each teller. This is why they’re still around; they’re constantly being reinvented. Just like the past when it is freed from the clot of history.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Shazia Hafiz Ramji’s fiction was shortlisted for the Malahat Review’s 2022 Open Season Awards. Her poetry was shortlisted for the 2021 National Magazine Awards and the 2021 Mitchell Prize for Faith and Poetry. Shazia’s award-winning first book is Port of Being. She lives in Vancouver and Calgary, where she is at work on a novel.