Writing Through Trauma Is Writing Through Forgetting

By Shazia Hafiz Ramji

A few days ago, I finished writing a short story. A new short story. Because my fiction is drawn from my life, I journalled first, did a freewrite, and then outlined the first half of the story to nudge me into a new world more easily, leaving the second half of the outline unwritten, with the hope that it would lead to a place I hadn’t been before. I got goosebumps and laughed and cried as I was writing the first draft, but partway through, I realized it was a story I had been telling for the last few years, that it was going the same way the other ones do, even though I hadn’t planned it … it wasn’t new at all. There was nothing I could do except finish it, even if it was just to see where it ended, if it ended. Even then, it was the same story I have been writing for years. I feel haunted.

I am always telling a story about leaving: Leaving lovers, leaving family, leaving for another self, leaving homes, leaving friends. All this leaving sounds like it’s about change, which is crucial for a character’s development, but it’s not about change. It’s not even about leaving. It’s about returning, repeatedly, to trauma.

When we talk about trauma, we talk about wounds, about the “I” telling their pain with strength in vulnerability despite the hurt that may cause, about the repercussions of that pain across generations, its echoes and the ways it manifests in the body, and about the voice that is suddenly being heard, that is no longer silenced.

We talk about memory when we talk about trauma, the way it appears in flashes and shards: all of a sudden, there is a face in the wood panelling of the café, a face you know from somewhere you can’t place; or a flash of a dead body on a dance floor on which you are completely clean, sober, and happy (and no one has died); or the intracranial sense that someone is watching you from within the bones in your back; or a sudden awakening at 3:45 a.m. with a strong physical urge to run, and so you do, and you keep running. But what are you running from?

You are running from something you can’t remember. You are running from something you don’t want to remember. Your body remembers what your mind can’t allow itself to. This is why stories about trauma are often stories of departure, at least for me, in diaspora.

In writing these stories about leaving, I found that I had forgotten many things. I have no memory of my first snow, for example, but it has to have been in London, England, or in Vancouver, Canada, sites of departure and arrival, sites of trauma and migration. I remember my dad announcing the snow, but I don’t remember seeing it. To write about my first snow – to write about my character’s first snow – I had to write through forgetting. I had to dwell at that site of the absence of memory, which means that I constantly returned to that moment in an attempt to recover it. And I was always trying to leave it, as if I were trying to escape but was in denial of my need to escape.

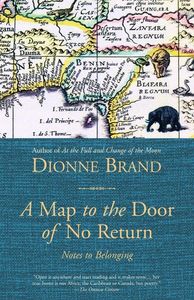

In Map to the Door of No Return, Dionne Brand articulates this absence in the metaphor of the Door of No Return: “The door signifies the historical moment which colours all moments in the Diaspora. […] The door exists as an absence. A thing in fact which we do not know about, a place we do not know. Yet it exists as the ground we walk. Every gesture our bodies make somehow gestures towards this door. What interests me primarily is probing the Door of No Return as consciousness. The door casts a haunting spell on personal and collective consciousness in the Diaspora. Black experience in any modern city or town is a haunting.”

The Door of No Return opens to the experiences of forced exile, migration, and leaving. It is the place where you were ripped apart from yourself forcefully, in shock, often against your will. It is the absence that feels like a haunting because trauma enables forgetting as a way of coping, so that your memory of the traumatic event is vague, doesn’t cohere, or simply isn’t there.

The Door of No Return is all the ways that you have been made to disappear yourself, which is why you keep returning – to pick yourself up again.

Accepting that I do not have certain memories, despite knowing that I once did – accepting that I forgot – allows me to revisit the site of trauma in writing in order to reclaim it with the fictive. With each fictive iteration and each layer of history and autobiography, I find myself surfacing, understanding the wounds that I have accrued around. As I find new words for those experiences (words whose fictions didn’t suffice, despite memory’s fictive nature to begin with), I am able to return to my body, to remember how to live again.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

Forgetting and memory go hand in hand, but the recognition of forgetting is what makes a return possible. It is the absence of memory that allows us a way in to write about trauma.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Shazia Hafiz Ramji’s fiction was shortlisted for the Malahat Review’s 2022 Open Season Awards. Her poetry was shortlisted for the 2021 National Magazine Awards and the 2021 Mitchell Prize for Faith and Poetry. Shazia’s award-winning first book is Port of Being. She lives in Vancouver and Calgary, where she is at work on a novel.