Zoom Class: Omar El Akkad and the Challenges of Writing Resistance

By Shazia Hafiz Ramji

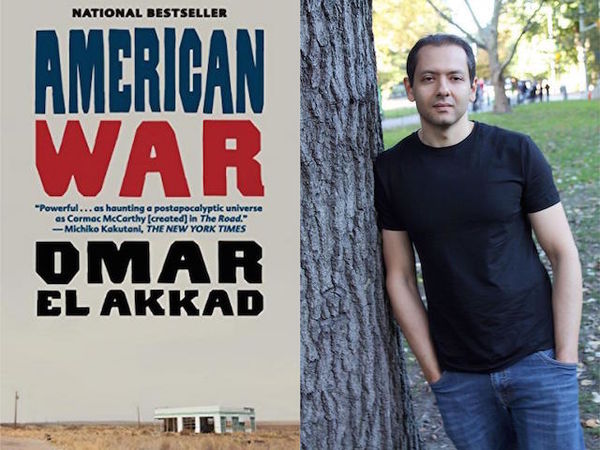

Sometimes there are Zoom meetings that can break you. Last week it took me five days to recover from the nausea, headaches, and light sensitivity caused by one single day of back-to-back virtual meetings. Other times, there are Zooms that can return you exactly where you need to be. “Style and Form in Resistance-Themed Fiction with Omar El Akkad” was one such Zoom. In this free talk organized by the FOLD in mid-January, I was grateful to learn about “resistance fiction” from the author of American War. It led me to understand the meaning of fear and loneliness, which continue to plague me as I work through yet another draft of my novel.

El Akkad says that “resistance fiction,” which stands in opposition to injustice, faces several challenges:

1) It has a harder time getting published because there are few precedents on which a publisher can base their sales estimates.

2) It also faces challenges in terms of how its read because there are no existing templates for that kind of book.

3) It might take years, decades, centuries for it to be understood in a way that is not at odds with how it was intended.

4) It has greater consequences. (El Akkad says that in his place of birth, Cairo, resistance fiction could mean jailtime or having your life threatened.)

5) It cannot “hide behind language” and requires a clarity of meaning.

“When you’re writing this kind of fiction,” he says, “you’re essentially trying to draw a map that is in some way fundamentally different from the prevailing map of the literary world. You’re trying to do something different…”

El Akkad discussed the representation of a Muslim woman on a true crime show: her hijab was sliding off and that became a plot point they had to navigate. The way she prayed looked more like yoga instead of prayer. El Akkad admitted that even though it was problematic, it was still a welcome change from the portrayal of Muslims as villains.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

“I was thinking a little bit about this sort of binary, like a rubber-band-snapping-back kind of mode of talking about human beings … we are conscious of the history of representations of this particular group that are cartoonishly evil, so we are going to fix that by having a cartoonishly virtuous character. And that’s going to offset all of the damage that was done…. I would caution against this idea of thinking you’re bound to binaries. Some of the most beautiful writing […] has gone into the place between.”

Recently I’ve been fearful of my novel. I thought I would feel less fearful as the drafts progressed, but the opposite has been true. The more complex my characters became, the more irreducible the story became, the more fearful I became. I am scared of how others will read my work, because my story is unusual and has not been told before. I am scared of being misunderstood. I am scared of becoming estranged from my kin again. I am scared of the historical repercussions that might reawaken. Because I’m writing autofiction, I’m also scared of the difficult truths on the page.

Writing can sometimes be so alienating, especially when we are writing autobiographically and breaking silence. But this is the very stuff of resistance – going where others haven’t gone before – doing something different because the story asks it of us. If I feel lonely and fearful it’s because the “novel” – in its adjectival form – is the “new, strange, unusual, and previously unknown.” My fear and loneliness are telling me I am scared, but I know now that it’s not a bad thing. It’s just a new thing. They are telling me I am exactly where I need to be, for now.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Shazia Hafiz Ramji’s fiction was shortlisted for the Malahat Review’s 2022 Open Season Awards. Her poetry was shortlisted for the 2021 National Magazine Awards and the 2021 Mitchell Prize for Faith and Poetry. Shazia’s award-winning first book is Port of Being. She lives in Vancouver and Calgary, where she is at work on a novel.