2017 Weston Prize Finalists on the Value of Non-Fiction: "Canada Needs to Know its Stories"

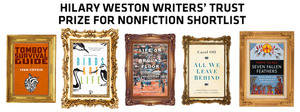

The jurors for this year's Hilary Weston Writers' Trust Prize for Nonfiction (Susan Harada, Arno Kopecky, and Siobhan Roberts) have set themselves a very difficult task. This year's shortlist is incredibly strong and varied, and the final decision is anyone's guess. The five deeply emotional and empathic books deal with trauma, tragedy, identity, grief, justice, and more.

Ivan Coyote is nominated their book Tomboy Survival Guide (Arsenal Pulp Press), which examines gender identity with sensitivity, wit, and insight. Kyo Maclear's Birds Art Life (Doubleday Canada) is a moving memoir centred around Maclear's experience birding in Toronto. James Maskalyk's Life on the Ground Floor: Letters from the Edge of Emergency Medicine (the second nomination for Doubleday Canada) is a harrowing but essential look at emergency medicine in Canada and elsewhere, while CBC's Carol Off is nominated for her powerful portrayal of an Afghan family defying injustice, All We Leave Behind: A Reporter’s Journey Into the Lives of Others (Random House Canada). The final nomination is the much-buzzed about Seven Fallen Feathers: Racism, Death, and Hard Truths in a Northern City (House of Anansi) by Tanya Talaga, which tells the heartbreaking stories of the deaths of seven Indigenous youths in Thunder Bay, and demands answers to those tragic, unsolved mysteries.

The winner of the $60,000 prize will be announced on November 14 at an event in Toronto, but today we are thrilled to welcome all five finalists to Open Book to chat about the experience of nominated, their books, and their own favourite non-fiction reads.

We hear which nominee started writing at a "squishy point" in their life, who ended up bleeding and bruised upon news of their nomination, and most importantly, exactly how each finalist views the reach and purpose of non-fiction.

Open Book:

How did your nominated book begin for you? What drew you to your subject matter?

Ivan Coyote:

This book began as a result of my touring public high schools with a storytelling based anti-bullying show. I wrote it to fill the space in me that could have used a survival guide when I was a little tomboy. For me it was so much more than a subject matter, it was my life. I was writing to work it out, to heal, to uncover, to resolve, to address, to remember.

Kyo Maclear:

I was at a squishy and uncertain point in my life, a bit grief-stricken, and was looking for a guide or guidance. I met a local Toronto musician who had lost his heart to birds. I imprinted like a duckling and followed him on an urban birding odyssey for a year. As a first generation immigrant brought up to regard “nature” with wariness and detachment, I was hungry to learn more about the city’s wild understory.

James Maskalyk:

Walking down the street with a friend of mine, on the heels of my book Six Months in Sudan, I was talking about my work in the ER, not what it consisted of necessarily, but the process from which it was born. It was, we decided, an enunciation of life caring for itself. The hospital was not a building, it was a giant white blood cell, drawing in hurt people, binding bodies too hurt to do it alone, alleviating pain, preparing people for their death. Could the universal laws that made it so be telling us anything else but to extend such care towards all humans, regardless of hour or means, then all living things? What drew me to the subject, was the slim but sturdy hope that this wasn't just a story I was telling myself to make sense of a senseless world, but one that might truly be the order of things. If so, then our shared work is to hasten it.

Carol Off:

This is a deeply personal book for me but it didn't start out that way. My initial idea had been to write a book that exposed the hurdles and horrors of the refugee system and how nearly impossible it is for asylum seekers to get anywhere. I set out to tell the story of one Afghan man and his family and what they had encountered: excessive bureaucracy, corruption, organised crime, the Harper government. But as I wrote the book, a parallel story emerged about journalism and its failure to properly protect sources who are willing to risk their lives and liberty in order to tell us things. And so it became a book about me as well, examining my own motives and obligations to the Afghan man and his family. How I had failed them. Ultimately, it also became a book about friendship, between me and them.

Tanya Talaga:

The book came out of a news article I first wrote in 2011. I had traveled to Thunder Bay to speak to Stan Beardy, the then-Grand Chief of Nishnawbe Aski Nation, a political organization of 49 First Nations in northern Ontario. Our interview was supposed to be about the federal election. But every time I asked a question, about why it is Indigenous people weren't interested in voting, he asked me why I wasn’t writing an article about Jordan Wabasse, a 15-year-old missing youth from Webequie First Nation. We had a back and forth for a bit, me asking questions about the election, him telling me about Jordan, until I stopped asking about politics and listened to what it was he was trying to tell me. He said Jordan was the seventh youth to either die or go missing since 2000 in Thunder Bay.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

Open Book:

Where were you when you received news of your nomination? What was your reaction?

IC:

I was lying in a dank hotel room in Dublin, Ireland, I was there with my band about to open a show for the Dublin Fringe Festival. I didn't get an official notice or anything, I just got the public email announcement from the Writers' Trust. I almost didn't open it right away, but I was jet lagged and couldn't sleep. I leapt up to run around my tiny hotel room with joy and whacked my toe on the wheel of my suitcase hard enough to bleed all over the rug.

KM:

Lounging in bed, half-awake, I opened an early morning email from my editor where she shared the news. My reaction was complete surprise and gratitude. I remain wowed by my fellow short-listers. Every single one of them is an inspiration to me.

JM:

I woke from a fitful, late-night shift sleep, to find a message from Frances Bedford from Doubleday. I leapt from bed and did a kind of high-stepping dance. It was, like...a running-in-place, but with more vigorous arm-pumping? It lasted about forty-five minutes.

CO:

It was early morning and I was in a car with Scott Sellers of Penguin Random House. We were heading to a breakfast TV interview. I saw the announcement on my phone but couldn't read it properly. Scott pulled over and we struggled to see the book cover images in the press release but they were the size of thumbtacks. Finally, we started getting messages of congratulations so we confirmed that one of the thumbtacks was All We Leave Behind. Very exciting.

TT:

I saw the news on Twitter as I was getting my kids ready for school. It took awhile for the enormity of the nomination to sink in. Being chosen as a finalist means that the story of the seven students will be brought to a wider, Canadian audience and for this, I'm extremely grateful because Seven Fallen Feathers is, at its heart, a story about Canada.

Open Book:

What unique experience or benefit does non-fiction provide for readers in your opinion?

IC:

I can't speak to how it works for other readers, but I can speak for myself and say that I am a fan of non-fiction because it is rooted in real people and real lives. It feels tangible, and relevant and immediate, even if it is historic. If it is done artfully and skilfully non-fiction has the ability to move me like no other genre can do.

KM:

Nonfiction is a big roomy category. I read promiscuously within it but I am particularly drawn to personal narratives that begin with the self and move beyond it—toggling between the book’s “I” and a wider, social “eye.” The subject needn’t be epic. I’m a firm believer that a small portal can lead somewhere unexpectedly large.

What I find benefitting as a reader is nonfiction that incites and entices me out of the silo of my subjectivity, or the tidy system I call my “worldview,” that invites me to understand the stage we’re at on this planet and, ideally, that lures me to imagine alternatives. As a writer and reader I really want to be taken and moved somewhere I hadn’t considered.

JM:

Perhaps a better named category than "non-fiction" is "loosely based on reality." One is limited by his or her own vantage, the way an objective world appears to a shifting subject, finite in time, almost opaque to itself. The power of non-fiction, in many ways, is these limits. There is no omniscience, only opinion, facts from which to choose, no fictions. In the end, even if the scope be as great as the history of the world, a reader knows it is tethered by a single person, complex and flawed and probably late for dinner. As such, it is a deeply human experience, a telling of the self, and if it illuminates a world previously unseen, for a reader, the real one changes for good.

CO:

I think non-fiction books are tricky to write and often not interesting to read. You can't invent or embellish your story (at least you shouldn't) so the story line can become thin very quickly. A non-fiction book lives or dies on its themes. You have to develop really strong themes in a non-fiction story that connect with universal issues and experiences. That's true of fiction as well, but the benefit of invention can keep a reader's interest in a novel even if the themes aren't strong. Non-fiction writers don't have that luxury.

TT:

Non-fiction is truth. Canada needs to know its stories.

Open Book:

Tell us about a favourite non-fiction book you've read.

IC:

Lidia Yuknavitch’s The Chronology of Water made me cry ugly on the plane one time. So beautiful and raw and brave. Jeanette Winterson’s Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal? Sherman Alexie’s You Don't Have to Say You Love Me, and his semi-autobiographical The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, both for bending their genres in all the right ways. The Glass Castle, by Jeanette Walls. Bury My Heart At Wounded Knee by Dee Brown. Bad Blood by Lorna Sage. In Cold Blood by Truman Capote is a classic, and I think birthed a lot of the genre we call True Crime these days. Me Talk Pretty One Day by David Sedaris.

KM:

I just finished and loved Draw Your Weapons by Sarah Sentilles. It’s a great work of creative nonfiction that melds memoir, cultural criticism and reportage. It deals with war and pacifism, destruction and creativity in the most searingly original, exquisitely crafted and utterly timely way.

JM:

Huston Smith's The World's Religions: Our Great Wisdom Traditions is one I recommend more than any other. It is remarkable as much for his even-handed exploration of our ancient and modern religions, the pivotal figures and geopolitical environs that allowed their purchase, as it is for his beautiful sentences. He finds the contemplative, beautiful core of seemingly disparate beliefs, and gives a reader the sense that the Buddha, Mohamed, Jesus, Confucius, if alive today, would weep over the fighting done in their name.

CO:

Anything by Erik Larson but my favourite is In the Garden of Beasts. Also anything by Adam Hochschild, especially King Leopold's Ghost.

TT:

I recently read, No is Not Enough, by Naomi Klein. It’s an engaging, well-argued read on how the world needs to wake up and refuse to be part of U.S. President Donald Trump’s ultimate reality TV show now taking place in America.

________________________________________________________________

Ivan Coyote is the award-winning author of 11 books and the creator of four short films, and has released three albums that combine storytelling with music. Coyote is a seasoned stage performer and over the last 20 years has become an audience favourite at storytelling, literary, film, and folk music festivals. Tomboy Survival Guide won the Stonewall Book Award for outstanding LGBT literature, and was longlisted for the BC National Award for Canadian Nonfiction in 2017. Coyote lives in Vancouver.

Kyo Maclear is a novelist, essayist, and children’s author. Her short fiction, essays, and art criticism have been published in Brick, Border Crossings, The Millions, Quill & Quire, Toronto Life, Azure, Saturday Night, and The Globe and Mail, among other publications. She is the author of two novels for adults, The Letter Opener and Stray Love, and numerous beloved books for children, including Julia, Child and The Good Little Book. Maclear is a doctoral candidate at York University where she holds a Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship. She lives in Toronto.

James Maskalyk is a physician, an assistant professor in the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Medicine, and a founding editor of the medical journal Open Medicine. His first book, Six Months in Sudan: A Young Doctor in a War-torn Village, about his experiences as a newly recruited doctor with Médecins Sans Frontières, was nominated for the Shaughnessy Cohen Prize for Political Writing in 2010. Maskalyk directs a program that works with Ethiopian partners at Addis Ababa University to train East Africa’s first emergency physicians. He lives in Toronto.

Carol Off is the host of CBC Radio’s As It Happens. She has covered conflicts in the Middle East, Haiti, the Balkans, and the sub-continent, as well as events in the former Soviet Union, Europe, Asia, the United States, and Canada. She has won numerous awards for her CBC television documentaries and was a finalist for the Shaughnessy Cohen Prize for Political Writing and the National Business Book Award for Bitter Chocolate: Investigating the Dark Side of the World’s Most Seductive Sweet. Off lives in Toronto.

Tanya Talaga has been a journalist at the Toronto Star for 20 years. She has been nominated five times for the Michener Award in public service journalism. She has twice won a National Newspaper Award for her work as part of a team: in 2013, for a year-long project on the Rana Plaza disaster in Bangladesh and, in 2015, for a series of stories into the inquiry on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. Talaga is the 2017–2018 Atkinson Fellow in Public Policy. She lives in Toronto.