"All the Good Stuff [is] Inevitable" Ray Robertson on First Sentences, Epigraphs, & Bookstore Love

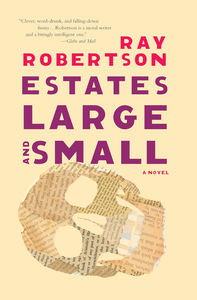

There have been a lot of unexpected casualties of the pandemic. For Phil Cooper, the protagonist of acclaimed writer Ray Robertson's newest novel Estates Large and Small (Biblioasis), who has battled for years to keep his used bookstore alive, Covid-19 is the final blow. Closing up the shop that has been his life's work is painful, and finding purpose afterwards feels nearly impossible.

But two things happen that change Phil's path, one internal and one external: he decides to embark on a journey to learn 2,500 years (yes, you read that number correctly) of Western philosophy, and he meets Caroline, who agrees, for her own reasons and in her own way, to join him on his quest.

A funny, thoughtful, and heartbreaking love letter to the power of books and reading, Estates Large and Small is Robertson doing what he does best – asking probing questions about why and how we can best live and understand ourselves and one another.

We're excited to welcome Ray to Open Book to discuss Estates Large and Small. He tells us about the importance of a book's opening sentence, takes us on a tour of Toronto in its secondhand bookstore glory days, and shares the meaning behind his Grateful Dead epigraph.

Open Book:

Do you remember how you first started this novel or the very first bit of writing you did for it?

Ray Robertson:

I can remember writing the first sentence—“Brick and mortar, horse and buggy, say hello to tomorrow today”—and knowing that I was in business. Voice is the most important element to a good book for me, as a writer and a reader, and can’t be faked. You know it when you write a “real” voice, just like you know it when you read it.

The opening sentence of any book is also the foundation of all that comes afterward. Not just tonally, but also thematically. The whole novel should be in the first paragraph, and if you’re really cooking, in the first sentence.

OB:

How did you choose the setting of your novel? What connection, if any, did you have to the setting when you began writing?

RR:

When I moved to Toronto in the mid-1980s, to study philosophy at U of T, it was still a city of second-hand bookstores. There was Queen Street West (Village Books, David Mason Books, Steven Temple Books). There was Harbord, near the university (Abbey Books, Atticus, About Books). There was even endearingly sleazy Yonge Street, which, if you looked beneath the grime and the garishness hard enough, was home to several passable to superlative bookshops (Elliot’s by far being the best of the bunch). And there was Bloor Street West, which was where you’d find Seekers (open until midnight!) and Book City (bereft of used books, but with tables and tables of inexpensive remaindered titles and also open late), plus, nearby, Ten Editions, only recently marked for demolition.

That was what was so wonderful about being surrounded by so many excellent brick-and-mortar second-hand bookstores at twenty-one or twenty-two years old: when you’re young and ignorant and eager, you don’t know what you want. You don’t know what you need. That’s what’s so intimidating but also so intoxicating (and advantageous) about the smorgasbord that is a hometown inhabited by an abundance of high-quality second-hand bookstores.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

Some of the most revelatory and life-altering reading experiences of my life were the result of nothing more deliberate or methodical than liking the way a book looked (William Barrett’s Irrational Man) or already admiring the work of someone who blurbed it (Thomas McGuane’s The Bushwhacked Piano) or because another book made owning it desirable (The Selected Poems of Delmore Schwartz) or because it was too cheap to pass up (a two dollar copy of a dust-jacketless first American edition of Celine’s Journey to the End of the Night) or for reasons long forgotten but likely no less capricious (Carson McCuller’s The Heart is a Lonely Hunter).

I wanted to write a novel that paid tribute to the world of second-hand bookstores, particularly now, when they’re becoming rarer and rarer. Without them, my life wouldn’t have been the same.

OB:

Did the ending of your novel change at all through your drafts? If so, how?

RR:

It always changes. Flannery O’Connor wrote that if a book in progress doesn’t surprise the writer, chances are it’s not going to surprise the reader either.

OB:

Did you find yourself having a "favourite" amongst your characters? If so, who was it and why?

RR:

For me, it’s usually a secondary character that sneaks up on you and becomes a “favourite”; whenever they amble on stage, they seem to supply a refreshing change of tone and pace.

I like it whenever Zoran, a Serbian refugee and former customer of Phil’s, the novel’s main character, shows up in the story. I never knew what he was going to say or do, which is always a good sign.

OB:

Did you include an epigraph in your book? If so, how did you choose it and how does it relate to the narrative?

RR:

Until things we’ve never seen

Seem familiar

– Garcia/Hunter, “Terrapin Station”

Like all the good stuff that ends up in a book, the novel’s epigraph didn’t feel like I chose it; it felt, when it occurred to me, inevitable.

Which, in a way, is what these two lines of lyrics from this Grateful Dead song represent to me: those bewildering, shadowy places in our lives where the unimaginable becomes the inexorable. Which, among things, is what Estates Large and Small is about.

______________________________________________

Ray Robertson is the author of nine novels and three works of nonfiction. His work has been translated into several languages. Born and raised in Chatham, Ontario, he lives in Toronto.