Anuja Varghese on Transformation, Literary Anxieties, and Writing for "Women Who Don’t See Themselves in Most Stories"

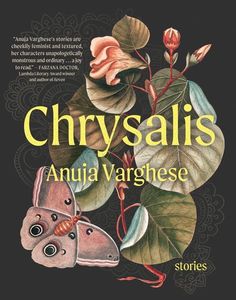

When it comes to genre, Anuja Varghese refuses to be penned in. Her debut story collection, Chrysalis (House of Anansi Press) is a highwire feat, balancing the surreal with the realist, the fantastical with the seemingly ordinary. But nothing about these stories are in fact ordinary, and Varghese's fiercely joyful experimentation is carefully and brilliantly controlled, with Varghese conducting literary symphonies in her pages. From a woman who can't stop dying in her dreams to a couple whose marriage woes attract otherworldly assistance, these stories originate from a world of Varghese's making that is both painfully recognizable and utterly—fascinatingly—unknown.

Populated by racialized women, queer characters, and even an unfairly maligned figure from Hindu folklore, Varghese uses her stories, and her singular voice, to not only play with genre constraints but to re-write narratives in which women, BIPOC characters, and LGBTQ+ folks have been under-utilized, under-explored, and under-represented in fiction.

Strange, urgent, and powerful, the stories are a delight. We spoke with Anuja about writing Chrysalis, and she told us about the self-doubt that crept in as she wrote and how she dealt with it. She shared as well about the figure of the vetala, the folkloric creature who may have been an early (and misunderstood) inspiration for Stoker's vampires, and why her inspiring dedication has not one, but two, possible interpretations.

Open Book:

What do the stories have in common? Do you see a link between them, either structurally or thematically?

Anuja Varghese:

Chrysalis is an intentionally genre-blending book – about half the stories have explicitly speculative elements, and half are based in the real world. Although, in these stories, even the real world turns a bit surreal sometimes. All the stories are linked by the theme of transformation and they all have in common South Asian diaspora main characters.

OB:

How did you decide which story would be the title story of your collection? Why that story in particular?

AV:

There are, unsurprisingly, several other books called Chrysalis out there! With that in mind, there was lots of back and forth about what the title story should be. Aside from embodying the book’s theme of transformation, the story that became “Chrysalis” was also the first story I ever submitted anywhere. I sent it (by mail!) to a writing contest. It made the longlist. Then I put it in a drawer and forgot about it for years. It has been through several edits and a name change since then (I have Matthew Harris at the Humber Literary Review to thank for suggesting “Chrysalis” as the story’s final title). In the end, there was a full-circle kind of moment to having the first story I ever sent out be the last story in the book, and the title of my debut collection.

OB:

Did you do any specific research for any of your stories? Tell us a bit about that process.

AV:

There’s a story in the collection called “The Vetala’s Song” that features an undead creature from Hindu folklore, called a vetala. I was actually researching South Asian myths and folk tales for the novel I’m working on, but there was something about this particular monster – she wouldn’t let me go. Further research uncovered that in the original myths, the vetalawas sometimes a guardian of its village, particularly the women. It was British scholar and imperialist Sir Richard Francis Burton whose translated tales of the vetala in the 1800’s characterized the creature as evil – a skeletal being with claws and a tail. Bram Stoker was apparently a fan of Burton’s work, and the vetala was likely an inspiration for Stoker’s Dracula, and subsequent popular depictions of vampires. How typical, I thought, that this complicated creature would end up twisted and maligned in white men’s hands. It felt right to let the vetala reclaim some power by writing her into a new story, and giving her a chance to sing.

A lot of the stories in Chrysalis take place in Toronto – in Parkdale and High Park, in Bay Street condos, and Bridle Path mansions. I lived in Toronto for almost a decade and the book is infused with those memories of place. But I also spent several days wandering around the city while I was pulling this collection together, visiting specific places to really capture their sensory details.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

OB:

What story collections were you reading for inspiration while writing your book? What did you learn from them?

AV:

When I was in the early stages of writing and workshopping the stories in Chrysalis, (this was approximately 100 years ago, in the pre-pandemic era), two short story collections came out that inspired me to try and write women who were messy and sexy and vulnerable and powerful; to write them as fearlessly and honestly as I could. Those collections were Tea Mutonji’s Shut Up You’re Pretty (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2019)and Jess Taylor’s Just Pervs (Book*Hug Press, 2019).

At the other end of the writing process – when I had a completed manuscript and was querying publishers – I started majorly second guessing the book, worrying that it was too weird or too queer or too rage-y. I read and re-read Sydney Hegele’s The Pump (Invisible Publishing, 2021) and it inspired me to just keep sending my stories into the world until they found a home.

OB:

Who did you dedicate your collection to, and why?

AV:

Chrysalis’ dedication page reads: “This book is for all the girls and women who don’t see themselves in most stories. You are worthy of reflection, despite what you have been told.”

The idea of being “worthy of reflection” can mean two things:

One – it can mean a throwing back or mirroring of. There were so few books with brown girl main characters when I was growing up. And even now, as an adult, bisexual, South Asian woman, I see myself reflected almost nowhere in mainstream media. So, in many ways, this is a dedication to myself, and to other readers who may discover a mirror somewhere in this book.

Two – it can mean worthy of serious consideration. The women who dominate the pages of this book are just that. They are not sidekicks or victims. They are not predictable or well behaved. They demand attention. And I want readers of this book to remember that they have that power too.

___________________________________________

Anuja Varghese is is a Pushcart-nominated writer whose work appears in Hobart, the Malahat Review, the Fiddlehead, Plenitude Magazine, Southern Humanities Review, So to Speak Journal, Flock Literary Journal, and Corvid Queen: A Journal of Feminist Fairy Tales, among others. Her work has been recognized in the PRISM International Short Fiction Contest, the Pigeon Pages Fiction Contest, and the Alice Munro Festival Short Story Competition. She writes literary fiction, speculative fiction, and erotica/romance — and combinations of all three — where women of colour get leading roles. Her stories appear in the BIPOC gothic anthology When Other People Saw Us, They Saw the Dead and queer horror anthology Queer Little Nightmares. Anuja is a professional grant writer, book reviewer, and fiction editor with The Ex-Puritan Magazine. She lives in Hamilton, Ontario, with her partner, two cats, and two kids. Chrysalis is her first book.

![banner image with photo of author Anuja Varghese and the quote "[I worried the book] was too weird or too queer or too rage-y." banner image with photo of author Anuja Varghese and the quote "[I worried the book] was too weird or too queer or too rage-y."](/var/site/storage/images/media/images/open-book-interview-banner-anuja-varghese-2023/113202-1-eng-CA/Open-Book-interview-banner-Anuja-Varghese-2023.jpg)