"Any Good Writing Involves Risk" Stuart Ross on Writing The Reality of Grief & Loss in His Striking New Memoir

One of CanLit's longest serving, most prolific, and most beloved poets, Stuart Ross has also published award winning fiction and creative nonfiction and served as a mainstay of the small press community for decades, famously even handselling his early chapbooks on the sidewalk of Toronto's Yonge Street.

His newest book is perhaps his most personal, a hybrid memoir that gently pushes against Ross' signature ability to turn tragedy into wry humour, looking instead, unflinchingly, at personal loss and grief.

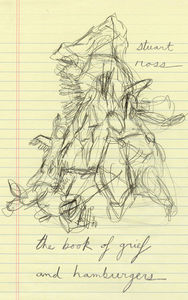

Still, it wouldn't be Ross without a bit of a cheeky wink and so, the appropriately titled The Book of Grief and Hamburgers (ECW Press) was born.

Poignant, raw, and honest, The Book of Grief and Hamburgers examines what life is like after we lose the ones we love. Written shortly after the death of Ross' brother, which left Ross as the last remaining member of his family, and following the terminal diagnosis of one of his closest friends, the memoir meditates on how we can continue to embrace the good in a relationship when one member of that connection is gone.

Ross, a former Open Book writer-in-residence, joins us today to discuss The Book of Grief and Hamburgers. He tells us about how he processed both the pain and comfort of writing about lost loved ones, putting aside (literally) ten other book projects to focus solely on the memoir, and the American writer whose hybrid memoir form so inspired him that he wrote her a thank you letter.

Open Book:

How did your memoir project first start? Why was this the right time to tell your story?

Stuart Ross:

In April 2020, just a month into the pandemic I received a very short phone call from my closest friend, the Ottawa poet Michael Dennis. He had just been diagnosed with terminal cancer. He likely wouldn’t live beyond the end of the year. Then, in June, my oldest brother, Barry, died, leaving me the last remaining member of the family I grew up as part of. I had already experienced the loss of many close friends, mentors, and family members, and I was overwhelmed. I have rarely viewed writing as a form of catharsis, but in September I set out to write a long essay about grief. I was determined to finish it before Michael died. Not so I could show it to him, but so it wouldn’t be about his death. I did end up showing him the dedication and epigraph: to and by him, respectively.

OB:

Is there a question that was central to this project? And if so, did you know the question when you started writing or did it emerge from the process?

SR:

I think I knew the question that I was trying to explore when I began writing: what is grief? And relatedly: can one ever get beyond grief, whatever grief is?

OB:

Did your memoir change significantly from when you first started working on it to the final version? Was there anything that surprised you about the process?

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

SR:

I had a stylistic/structural approach to start with — a kind of hybrid essay/memoir/poem — but I didn’t know where it would go. Or where I would go. The writing was often excruciating and painful, so I was beyond the capacity to experience surprise. I should add that the writing also sometimes brought comfort: perhaps because I knew I was honouring people very important to me. As I wrote, I thought about expanding the subject of loss to include friends from whom I’ve become estranged, and people who died who were important to me but I didn’t know personally. But I decided to keep the focus narrow and the book short: the loss, by death, of those very close to me.

OB:

What do you do if you’re feeling discouraged during the writing process? Do you have a method of coping with the difficult points in your projects?

SR:

I generally dislike the process of writing. I usually have to force myself. So if I’m feeling discouraged or hostile to the process, I guilt myself (my therapist, an existentialist like me, called me “a funnel of guilt”): if I don’t write, what use am I? I also usually have several projects going at once, so when I’m sick of one of them, or run into a brick wall, I switch to another. But for The Book of Grief and Hamburgers, I put aside the other ten (really!) books I’ve started and concentrated solely on it.

OB:

Did you experience any anxiety about making a part of yourself public in this way? If so, how did you or do you cope with the vulnerability of publishing a memoir?

SR:

I don’t know what’s going to happen when people get their hands on that book and read it. I believe that any good writing involves risk and making oneself vulnerable: and it always worries me to some extent. With this book, my greatest anxiety was about revealing things about those who’ve died that they might not want revealed. But it never really became an issue. I wrote that book so full of love for those who had died and the friend who was dying.

OB:

Were there any published memoirs you found inspiring structurally or otherwise while working on yours?

SR:

I was wrestling with my fears: my fear of death, my fear of losing loved ones, my fear of never being able to escape the pain of loss. It didn’t occur to me to actually write about it until I was rereading the works of a brilliant New York writer, Amy Fusselman. Idiophone, 8, and The Pharmacist’s Mate in particular. They are kind of essays, kind of memoirs, kind of poems. Like me, Fusselman seems to like writing very short books. But she has this amazing approach: spaced-out paragraphs, repetition, a kind of focused but simultaneously free-form structure. As I read her, I saw that if I emulated her form, or some aspects of her form, I could perhaps work through the pain and fear I was experiencing. When I finished the book, I wrote her (I don’t know her) and thanked her for providing a path for me.

OB:

What are you working on now?

SR:

As I mentioned, I work on a lot of projects at once. I’m finishing off my third short story collection, which will be published in the fall by Anvil Press. I’m working on a manuscript of one thousand tiny poems. Three short novels, as well. Gathering together what will be my twelfth (I think) book of miscellaneous poems. Another memoir, very different from this one. And a book of one hundred two-page short stories. Then there are a few collaborative poetry projects: with Jaime Forsythe, Jason Heroux, and Mahaila Smith. At least two of those will be full-length books. I thrive in creative chaos. As you might have noticed.

________________________________

Stuart Ross is the author of 20 books of fiction, poetry, and essays. He received the 2019 Harbourfront Festival Prize, the 2017 Canadian Jewish Literary Award for Poetry, and the 2010 ReLit Award for Short Fiction. His work has been translated into Nynorsk, French, Spanish, Estonian, Slovenian and Russian. Stuart lives in Cobourg, Ontario.