Artist & Poet Matthew Hollett on Optic Nerve, His Witty, Poetic Love Letter to the Act of Looking

What doing writing and photography have in common? Certainly both can be records, both necessarily show the creator's perspective – and both can crack open new worlds, crystallized stories, or spectacular moments.

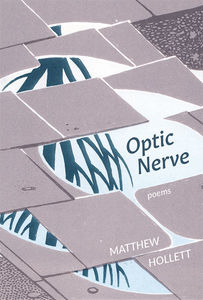

This thematic overlap between what we see and how we write, process, and feel occupies Newfoundland artist and author Matthew Hollett's playful, smart new collection of poems, Optic Nerve (forthcoming from Brick Books in April). Hollett, a multi-disciplinary artist, is known for his ability to blend humour, insight, technology, and humanity in his projects.

Optic Nerve looks inside things as varied as eyeballs (naturally), quarks, street art, and potatoes, and in Hollett's hands, each act of looking becomes a meditation, not silent and solemn but riotous and vibrant, with the excitement of catching a glimpse of beauty through a keyhole.

We're speaking with Matthew today about Optic Nerve, as part of our Line & Lyric interview series for poets. He tells us about his love of ekphrastic poems ("writing in response to images"), reveals the iconic experimental writer whose work inspired him during the writing process for Optic Nerve; and describes his poetic approach as "something between a lecture and a stand-up routine".

Open Book:

Tell us about this collection and how it came to be.

Matthew Hollett:

Optic Nerve is a collection of poems investigating photography and visual perception. As a photographer and writer, I often go for long walks with my camera. I make notes while I’m wandering – little observations, things I notice and want to remember. And of course my photos are a kind of notebook, too. So it’s a collection born of walking and looking, footsteps and snapshots.

I love ekphrastic poems – writing in response to images – and Optic Nerve contains poems inspired by Japanese paper, painter Édouard Vuillard’s mesmerizing interiors, and flies in still life paintings. A linocut print of boat-builders in rural Newfoundland is reimagined as peering inside of an eyeball. Several poems explore the work of street photographer André Kertész, known for his offbeat, slightly surreal images of the streets of Paris and New York.

Putting this collection together has been a long process of revising, revisiting, and re-envisioning. The poems in the book basically span the entirely of my twenties and thirties. I’ve moved a lot during those years, and so the writing crisscrosses St. John’s, western Newfoundland, Halifax, Montreal, northern California and elsewhere.

OB:

Can you tell us a bit about how you chose your title? If it’s a title of one of the poems, how does that piece fit into the collection? If it’s not a poem title, how does it encapsulate the collection as a whole?

MH:

My poems use inventive language and wordplay to examine visual culture and the act of seeing, so Optic Nerve seemed a fitting title for the book. I’m usually pretty quick with titles, but this one was elusive. I have a long list of rejected titles, including Peripheral Visions, Split Seconds, and Skitch (in The Dictionary of Newfoundland English, to be “skitched off” means to be photographed). The phrase optic nerve appears once in the book, in a poem about entoptic phenomena.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

I’m really pleased with how the title resonates with the cover image, which is a detail from a lithograph by Jon McNaught titled Puddle. Jon’s graphic novels (Kingdom and Dockwood) are gorgeous meditations on rural landscapes and the small details and patterns of everyday life, so it feels like his work fits the spirit of Optic Nerve for that reason alone. But Puddle seems especially appropriate – the oculus of the puddle and the upside-down reflection remind me of photography, and the tree shape is even a little evocative of a nervous system.

OB:

What were you reading while writing this collection?

MH:

Italo Calvino is my favourite writer, and at one point while writing this collection I reread his wonderful Six Memos for the Next Millennium. It’s a series of lectures on literature, but the writing is as warmly imaginative as any of Calvino’s novels. The essays are conversational, discursive, and elliptical, more literary philosophy than criticism. Calvino contradicts and wonders at himself, weaving threads together with graceful, lucid self-awareness. For me, the book is a timely reminder of how to see the world generously and humanistically.

I also love books about walking, photography, and seeing. Teju Cole is an incisive writer and photographer whose novels (Open City and Every Day Is for the Thief) capture the complexities of walking through cities densely layered with landscape, language, culture, and memory. A few other favourite books about walking and writing are Rebecca Solnit’s Wanderlust, Simon Armitage’s Walking Home, and Nan Shepherd’s The Living Mountain.

OB:

Is there’s an individual, specific speaker in any of these poems (whether yourself or a character)? Tell us a little about the perspective from which the poems are spoken.

MH:

One of the poems is a monologue (more or less verbatim) from a security guard who very politely kicked me off a construction site for taking photos. Another is a kind of whimsical sermon imagining the possibility of pinhole cameras occurring naturally on other planets. Mostly the poems are my own voice, occasionally lilting into something between a lecture and a stand-up routine. I write with the idea that the poems will be read aloud, so sound and cadence is very important to me.

OB:

What advice would you give to an emerging or aspiring poet?

MH:

I keep a daily journal, and these notes and observations are often where my writing begins. They’re not necessarily personal, just things I want to remember. Sometimes they’re more like field notes, sometimes poem fragments. A noise outside that drew me to the window, or how the horizon looks. It’s something I’ve been doing since high school – I have boxes and boxes of old notebooks and journals. These days I mostly make notes on my phone.

I’ve been publishing writing and making visual art for years, but my journal sometimes feels like my longest, most sustained creative practice, although no one ever sees it. Sustaining is a good word for it – it carries me along. I’m usually happiest when I’m writing the most.

Writing things down as they happen is key, as that kind of immediacy is impossible to capture afterwards. I often sift through my journal to find small details when working on poems and essays. It especially comes in handy when writing fiction, as those small sensory impressions are what makes a story convincing.

____________________________________________

Matthew Hollett is a writer and visual artist in St. John’s, Newfoundland (Ktaqmkuk). His work explores landscape and memory through photography, writing and walking. His first book, Album Rock (2018), is a work of creative nonfiction and poetry investigating a curious photograph taken in Newfoundland in the 1850s. He won the 2020 CBC Poetry Prize for “Tickling the Scar,” a poem about walking the Lachine Canal during the early days of the pandemic. He has previously been awarded the NLCU Fresh Fish Award for Emerging Writers, The Fiddlehead’s Ralph Gustafson Prize for Best Poem, and VANL-CARFAC’s Critical Eye Award for art writing. He is a graduate of the MFA program at NSCAD University.