Bill Richardson on Sharing Writing Space with Irving Layton and Robertson Davies

"In this last week, there are seven days."

In Bill Richardson Last Week (Groundwood Books, illustrated by Emilie Leduc), a child knows they've got a week to spend with their grandmother. But unlike a normal visit or vacation, this is the last week ever, as Richardson, often known for his witty comic offerings (with a Stephen Leacock Medal to prove it), gently and thoughtfully explores the realities of medically assisted dying through the eyes of a child.

In the surreal final, titular week, we see the child witness Flippa, the grandmother's, resolve, self-determination, and acceptance, and the love, humour, awkwardness, and nostalgia of her loved ones.

Richardson's nuanced treatment of a deeply complex issue is inspiring and touching, not only in his rendering of Flippa and the unnamed child's emotional journeys, but in his holistic exploration of how this particular kind of death can effect a family and a legacy. A supportive voice in a contentious conversation, Richardson's story is accompanied by an afterword and additional resources by MAiD (Medical Assistance in Dying) expert Dr. Stefanie Green.

Today, in celebration of the upcoming (April 1, 2022) publication of Last Week, we're proud to host a piece written by Richardson as part of our At the Desk series, where we invite writers to share with us about spaces, especially unique ones, that have been influential in their writing lives.

He shares the very relatable (notably cutting board-based) "Richardson Method of Writing" before taking us to pre-pandemic times, when he landed a writer-in-residence gig with a very neat perk: the discovery of a guestbook signed by some of CanLit's departed titans, each with their own personal twist.

At the Desk with Bill Richardson:

My writing set-up is as uninspiring as ever you’ll find. I live in a viewless apartment, so tiny it doesn’t even meet the bar for “bijou” status. Owing to my late-life, semi-fatalisitc devotion to austerity and emptiness, I keep it minimally furnished. I don’t have a dedicated desk or region where I repair on those rare occasions when I feel moved to smith some words. Instead, I take a breadboard. I purge it as best I can of the crumbs and jammy bits. I fold down the Murphy bed, lie prone upon it, and prop myself up on my two flat, un-plumpable pillows. I put the breadboard on my lap, put my laptop on the breadboard and wait for the magic to happen. Mostly, I indulge in fits of diurnal somnolence. I mean, I nap. The Richardson Method of Writing is not one I would recommend to anyone. It ensures minimal productivity and places undue strain on the lumbar.

The last time I had a desk was during a three month stint at the University of Manitoba’s Centre for Creative Writing and Oral Culture. This was in the Fall of 2019; I’d been lucky enough to get a Writer In Residence gig. This, of course, was just as Covid was massing beyond our borders. I look back now at all those unmasked, in-person meetings with all those writers, with all their promising manuscripts, and wonder, how did that ever happen? It was a wonderful time, for many reasons, and unlike the Richardson Method of Writing, see above, I would recommend that job and that place to anyone who might think to apply.

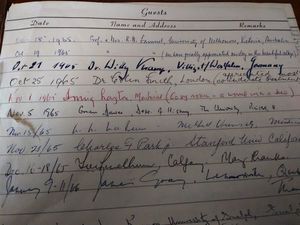

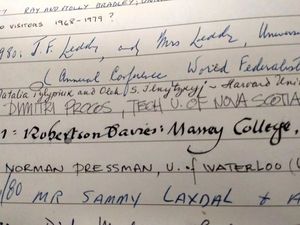

A great perk of the residency was that it included the use of a spacious one-bedroom apartment, very quiet and private, tucked into the back of the main floor of the student residence at University College. It’s intended for the short-term enjoyment of visiting faculty, or academics attending the conferences and colloquia that were once so much a part of University life and, surely, will be again. The apartment was not exactly Spartan in its arrangements, but no one would ever call it luxurious, either, which suited me fine. It was plainly furnished and some of the pieces — Danish modern — had been there, I think, for as long as the College itself, i.e. more than half-a-century. Among them was a drop-top desk, lovely in its purposeful lack of fussiness. Within the desk, layered in its three drawers, were random oddments, cast-off remnants of some of the previous transient tenants: campus maps, “What’s On In Winnipeg” magazines from years gone by, a jigsaw puzzle, and so on. All that was remarkable, really, was the Guest Book, extremely battered, coming apart at the binding. Here, the various worthies who'd passed through, mostly for stays of a night or two, had appended their names, the dates of their visits, and, now and again, a comment or appraisal.

Among them were some distinguished Canadian writers who came to the fore in the years after the war and were foundational to the creation of our national literature. Here was Irving Layton, in 1965, noting: “Cozy room, a womb with a Jew.” Earle Birney, visiting in 1967, must have perused the document to see who else had slept in his bed, and offered in wry reply, “A joy for a goy and a suite for a beat.” Robertson Davies, in 1980, didn’t deign to offer any kind of descriptor or assessment, merely noted, in fine calligraphic hand, the fact of his august presence and his Massey College affiliation. Neither Gwendolyn MacEwen nor Miriam Waddington offered anything other than autograph or date when they dutifully placed their Jane Henrys in the same books that Noam Chomsky, Irving Howe, Ralph Miliband and many other writers, academics, activists, and politicians had signed.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

The desk where lived the Guest Book was functional, but small, well-suited to the writing of short thank you notes or to-do lists, but not suited to my purposes. I chose to leave it as a shrine inviolate, and worked instead at the dining table, which accommodated spreading out, and offered room for coffee and other necessary fuels. It was there, over the space of a few hours in September of 2019, early in my 3-month tenure, that I wrote the text for Last Week. I remember the beautiful light of a prairie day in early autumn, and the voices of students as they passed outside, and the great gift of that rare (for me) feeling of time being absent, of knowing exactly what I wanted to say, and how I wanted to say it; remember the feeling that I was taking dictation from the child narrator, who tells the story of how it felt to be with their grandmother as she prepares to die. I started and I finished, beginning, middle and end, and it felt right, complete, whole. Hardly a word was changed after Groundwood Books kindly agreed to publish it, and to engage Emilie Leduc to make beautiful illustrations. I don’t flatter myself to think that the ghosts of Earle or Irving or Robertson or Gwendolyn, or any of the others, were there, urging me on, but I enjoyed then, and over the course of my stay, a sense, however irrational and enfeebled, of being in communion with them.

I worried about the Guest Book, too. Its value was self-evident. It didn’t reveal much about anyone or anything, but it was a record of comings and goings, a tangible reminder of who had passed through. If nothing else, it was charming, and charm is a commodity in short supply these days. That it was just there, in that room, where anything might happen to it, seemed wrong. I wanted it preserved, formally. Selfishly, too, I wanted to be the final signatory. So, on the last day of my tenure, at the end of November, as all the world was poised to pivot and change, I signed the Guest Book, put it in an envelope, and took it the archivist at the University Library. I explained what it was and how I thought it should be kept safe, and she agreed. It was, as it turned out, her last day on the job. She was retiring, after many years, and it would be her final acquisition. That seemed to me to be as it should be. Somewhere, among all the other treasures, in its time-repelling box, the Guest Book waits for whoever comes along next. If anyone ever searches it out, I’d love to know what I wrote, by way of a comment. I can’t remember at all.

_____________________________________________

Bill Richardson, winner of Canada’s Stephen Leacock Memorial Medal for Humour, and former radio host, has written several highly acclaimed books for children. They include The Aunts Come Marching, illustrated by Cynthia Nugent, winner of the Time to Read Award; After Hamelin, winner of the Ontario Library Association’s Silver Birch Award; and The Alphabet Thief, illustrated by Roxanna Bikadoroff, named among New York Library's Best Books for Kids. Bill lives in Vancouver, British Columbia.