"Bison, Teeth, Talking Trees, Screaming Purses" The 2021 Griffin Prize Poets Tell Us the Images That Recur in Their Work & Share Recommended Reads

Every year, the poetry world turns its attention to Canada, to discover the winners of the Griffin Prize, the biggest poetry award in the country and one of the leading awards in the genre worldwide. Each year, one Canadian poet and one international poet (hailing from any other country, and including works in translation) are each honoured with a $65,000 prize. Past winners include luminaries like Anne Carson, Paul Muldoon, John Ashbery, and Dionne Brand.

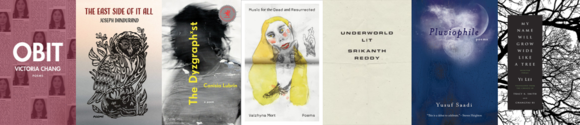

This year, the Canadian prize nominees are Joseph Dandurand for The East Side of It All (Nightwood Editions), Canisia Lubrin for The Dyzgraphxst (McClelland & Stewart Ltd.), and Yusaf Saadi for Pluviophile (also Nightwood Editions).

The international nominees are American poet Victoria Chang for Obit, Belarusian poet Valzhyna Mort for Music for the Dead and Resurrected, Indian-American writer Srikanth Reddy for Underworld Lit, and translator team Tracy K. Smith and Changtai Bi, who translated the late Chinese poet Yi Lei's My Name Will Grow Wide Like a Tree.

We're thrilled to be speaking to the finalists today about their work and the experience of being nominated. In our conversation, the poets tell us about images and themes that seem to crop up repeatedly in their work and thought process, share their favourite Canadian poems, and take us through their writing days, including the benefits of early mornings and "spacious wondering".

The winners, chosen by jury members Ilya Kaminsky, Ales Steger, and Souvankham Thammavongsa, will be announced June 23. The finalists in each category apart from the winners will receive $10,000.

Open Book:

Tell us about your nominated collection and how the project originated for you.

Victoria Chang:

My poetry book, OBIT, emerged out of absence and resistance. My mother passed away in 2015 after a long illness and I remember actively resisting writing poems in general and conventional elegies specifically. When I heard on NPR, a piece on the documentary “Obit,” I remember thinking that so much dies when someone dies, that there are a lot of “little deaths” and I went home and wrote the first poem in this book. Then I wrote another and another until two weeks later, I had around 70 of these small obituary poems.

Joseph Dandurand:

The East Side of It All was published by Nightwood Editions and it is the second book they have since published for me the second being an illustrated children’s book. I had so many finished manuscripts of poetry and I would send when they were completed and this book was next in line of a series of completed manuscripts. I had been working and giving readings on the eastside of Vancouver and was met by the many indigenous brothers and sisters who were addicted to heroin and this began the poems and included was my past of alcohol and drug addiction and also my spirituality and my connection to where I live and the river and the ceremonies and the myths and creatures we are surrounded by here in Kwantlen where we have been for over ten thousand years since we fell from the sky or so our story goes.

Canisia Lubrin:

The Dyzgraphxst is one of my early attempts to disturb the solidity of modernity, without leaving beauty out. It is a poem structured as seven theatrical acts... each of which is guided by a central curiosity: how does personhood, or the self, come to be in relation to others and the world’s wider ecologies? Given a human-made world, like our current world, which is threatened by climate crisis and the history and continuance of imperialism and capitalism, the title plays on the word dysgraphia, which has Greek roots, meaning ‘difficult writing’ or ‘to have difficulty writing’, or in my more loosely metaphoric interpretation, to write difficult things. The origin of the book is in the aforementioned central question, but it is shaped through Christina Sharpe’s idea of the wake as a condition of Black people’s lives after slavery. You can (and should) read more about this in her book In The Wake: On Blackness and Being. The environment in which the poem moves is our crucial moment of global reckoning in the still young 21st century. What does that mean for the poet? For a poet like me, who is alive in, aware of, and works with the history and contemporary materials of Black personhood, I take to the page the language of so much that has been made of human knowledge and progress and so-called democracy, toward troubling their more obscure meanings. What (or whose) purpose do individualism and humanism really serve in this world of rapidly expanding ecological collapse and inequality? It is really easy to wax on about things that make people seem wise and all-knowing when the anecdotal and solipsistic are praised as the only evidence of our truths. But, I was more interested here in what language can do in the future tense of imagination. I found another what-if: what if the things that really push us through catastrophe are the things we don’t fully understand, even as we have multiple overlapping capacities to sense, to make sense, half-sense, broken-sense? At core, this is a book about the self, kinship, language, and the turbulence of how worlds are made.

Valzhyna Mort:

To say where my work originates is to answer the question of where I myself originate. Since my childhood in the capital of a provincial Soviet republic, I have been amazed with certain stories of survival, hunger, absence, music, violence, memory, propaganda, history, Chernobyl radiation. I have been amazed with the streets of Minsk, its giant monuments, its trees, its light, its missing politicians, its densely packed residential areas where I grew up. I was obsessed with the dead: my own empty family archive as well as the unmentionable sights of mass executions in nearby forests. I thought that the dead were everywhere: in the patterns on wallpaper, curtains, carpets. That said, I believe my collection is a very funny book.

Srikanth Reddy:

Underworld Lit is a long poem that tells the story of an untenured professor who undergoes treatment for cancer while teaching a university course called “Underworld Lit.” He’s also trying to parent a small child and translating an old Chinese folktale (though he doesn’t know any Chinese), and there are a couple of wars going on overseas in the background. It all sort of goes sideways from there. In the end, the translation pretty much takes over the story—but it’s not a very faithful translation.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

The project originated pretty much by accident. It just kind of happened to me.

Yusaf Saadi:

I didn’t have explicit guiding themes or a concept for the collection as a whole before writing, so the poems are wide-ranging. Some originated from scattered jot notes I made while in Kolkata, or at 3:00am in Victoria, BC, procrastinating writing academic papers, some when I was feeling depressed and/or walking around Montreal aimlessly. Others maybe had less to do with physical places and more to do with sitting with my emotional states, working through them.

Tracy K. Smith:

In 2014, my Chinese translator Yuanyang Wang, suggested that I meet with a very special poet who would soon be visiting New York. A few days later, via Yi Lei’s friend Nancy Bumin, I received Changtai Bi’s translation of Yi Lei’s poem "A Single Woman’s Bedroom." By the time I finally met Yi Lei fact to face, I was so enraptured by the beauty, courage, and insistence of her voice that I knew I wanted to dwell a while in her imagination. Via the translation process, Yi Lei, Changtai Bi, and I embarked upon a years-long dialogue about poetry, freedom, life, and the human spirit. For me, this has been life-changing.

Open Book:

Are there images, themes, or questions you notice recurring in your work? If so, what are they?

VC:

There are probably a lot of images, themes, and questions recurring in my work because I have a very obsessive personality and also tend to write over a short period of time (hence the sometimes difficult problem of being overly consistent). Obviously, my most recent book of poems circles around the theme of grief and death. I think I am always thinking about things so I think whatever it is I’m thinking about tends to show up in my work. I am also interested in memory, history, and identity.

JD:

For sure I am constantly shown things here for example an eagle flying over my head or a day of fishing on the river where I am given glimpses of things I may not understand at the time but I store these images and when I sit down and write a poem they reappear and they become the emotion of the piece. I write a lot about religion and in most cases it is tragic and that is because my mother was five years old when she was taken from her home and sent to residential school which also is seen in my work. I also write a bit about my stay at many mental hospitals and the characters I met there and by writing about all these things it is very tragic and cathartic in the same breath. I write about my three kids too as they are my world and they are why I write and I will always love them as they love and care for me in my loneliness of being a reclusive poet and man.

CL:

I am not moved by themes. I have a curiosity about the world, I have an imagination that leads me to language through many different roads, I have a deep ethical awareness of my history and place and time as a Black woman who makes art. I am interested in collaboration, and I appreciate intensely that art plays important roles in how we make beautiful lives in a precarious lifetime.

VM:

Bones, bison, teeth, talking trees, screaming purses, apples, accordions, buses and trains, swings, storks, snow, bread, ghosts, radiation, music, language, gooseberries, reflections. What is language for if so much has not yet been said with ordinary words? What is language without music? Where are plain words when I need them? I try to create magical music out of plain words.

SR:

Inkblots, Chinese characters, pyramids, multiple-choice tests, twins, and dragonflies. There are more, but I think this sort of gives a general picture of things.

YS:

Beauty, I think is one, and also the relationship between imagination and world — and perhaps how language hovers within those realms, threading them. In hindsight, I realize a lot of the poems also contain questions — Why can’t we harness sound for energy or power a skyline by Chopin? Could the rain build a flower so mountainous it wouldn’t fit inside a human word? What is it like for the dead to talk across the surface of a star? — some of the poems then might be reflections on these necessarily imaginative questions, though I don’t think I really present any answers, perhaps because there are no definitive ones.

TKS:

In this book of Yi Lei’s selected poems, there are many recurring images of the natural world—waterfalls, rainstorms, floods, trees, clouds—even the very grass that lives in the work of one of Yi Lei’s poetic kindred-spirits: Walt Whitman. This is a poetry that honours the earth as a living being, and pays honour to its many manifestations. These poems are also committed to freedom: from the freedom to live and love as one wishes, to the freedom of mind, spirit and consciousness.

Open Book:

Tell us what a typical writing day (if such a thing exists for you) looks like while you're working on a collection.

VC:

When I am working on something or actively in that obsessive mode, I am pulled toward whatever that is. It feels very magnetic but my days can get very busy so I end up spending most of my weekend days trying to get back to whatever it is I’m obsessing about. I would say email is the biggest problem for me—an email comes in, usually asking for something from me, sometimes from people I don’t know (and I try to answer every email I receive), I answer it, feel elated for answering all my emails, and then the same number of new emails comes in, and the cycle continues and never ends.

JD:

I get up every day at five a.m. and I drive into town for a cup of coffee and then I drive back to my office and I move all these trinkets on my desk and then a I put x’s on a calendar on my wall and then I sip my coffee and I turn on some music and in most cases of a manuscript it is one song I replay over and over and then I will start with a title and then I drop into the poem and these days the style of my poems are all with 3 paragraphs and sometimes they are connected but in most cases they become 3 different scenes and I am currently 90 pages into my latest manuscript and soon it will be over and I am always thinking of my next project and I may take a couple of days between project more never more as the need to create overcomes me and so I carry on waking up at 5 am getting a copy and repeat the process with of course a new song to play and play.

CL:

My life doesn’t allow me the stability of the typical. I write when I have time to write. For my first three books (the third is fiction and I am currently editing it), I have done a lot of writing during three and six in the morning, in the quietness and amplitude of those hours.

VM:

I do a lot of my writing in my head, at any given moment, so poetry for me is a way of living, a method of being a human. What is writing? Paying attention, feeling amazed, allowing your obsessions to lead you deep into language. What it often looks like from aside: a person spends all day exclaiming “ah!” and “no!” as she moves three words around the page.

SR:

I try to work every day (except weekends). I write in the morning, in my office at work, from 9 to noon. Then I start answering emails and doing other things for my job at the university. I work for a long time on a book, it seems. The last one took seven years. This one took about eight years. So I’m slowing down, I guess.

YS:

Taking naps, looking at pictures of South Asian food, taking walks and bike rides, and maybe writing a few words... I don’t really have a typical writing day at the moment, especially during the pandemic; I’m mostly trying to stay afloat.

TKS:

My writing life has many forms. When I am able to enter into a dedicated period of work, I wake up, get my kids off to school, and spend the rest of the day reading, thinking, and building poems. I can write in the busier periods when work and other commitments make demands upon my time. But the most powerful and transformative writing, for me, comes during times of dedicated focus, when I can enter into what feels like a spacious wondering.

Open Book:

If you were to recommend just one Canadian poem (or poetry collection) to readers right now, what would it be and why?

VC:

I really enjoyed Sina Queyras’s My Ariel, which was published a few years ago. I found the language and the thinking, as well as the frame of the book, to be interesting and refreshing.

JD:

I would recommend Ego of a Nation by Janet Rogers published by Ojostoh Publishing. I have always enjoyed Janet’s work this book of poems kept me until the end and most do not do that for me and she has such and insight and passion for words and the people where she comes from and that we are similar in our love for our people and our past and our future and we share the gift which have for joining words together into poetry. She is a great writer and friend and I will always pick up one of her books and so should you if you so desire.

CL:

Inventory by Dionne Brand. A dirge for this historical moment.

VM:

The Canadian Griffin list is brilliant. Dear judges, thank you for honouring such important poetic works as you bring them to a wider readership. Another Canadian poetry collection that was published this year is Michael Prior’s Burning Province. I love it and highly recommend it.

SR:

The Pillow Book by Suzanne Buffam. Read it and you’ll see why!

YS:

I’m in awe of heft by Doyali Islam – I’ve been returning to it over the past year, and I’m still not over it. Her gift of attending to the world, with a kind of quietness, seems like a way of being most egos would have to spend years trying to attune themselves to. It’s also revitalizing on so many levels, from her invention of the double-sonnet form to her absolutely breathtaking imagery. My favourite poem may be “amble.”

TKS:

In her masterful collection Zong!, M. NourbeSe Philip has made an extraordinary contribution to the field of documentary poetics. In its exploration of archival material, Zong! illuminates the brutal erasures against Black life enacted in the name of profit and law, while also managing to gather, resurrect, honor and invoke the names, voices, and spirits of victims of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. A great strain of literature has sought to correct and expand the prevailing narratives of Black life and Black subjectivity. Zong! does these things like no other work of literature I have encountered, perhaps because it guides readers to dwell simultaneously in regions of the mind that typically remained siloed from one another. The effect feels like nothing shy of a reconstituting of history and a re-integration of the Black self.

____________________________________________

For more information about The Griffin Poetry Prize, please visit their website