Brit Griffin's Latest Novel is a Haunting Gothic Mystery in the Northern Ontario Wilderness

In The Haunting of Modesto O’Brien, author Brit Griffin transports readers deep into the northern wilderness with a gothic mystery that thrums with danger, magic, and raw emotion. Set in 1907, the novel follows fortune-teller and reluctant detective Modesto O’Brien as he navigates a fledgling mining town gripped by silver fever. Men come seeking fortune, but O’Brien arrives with darker motives, namely revenge. What begins as a search for justice soon becomes something far more terrifying as the wilds of the boreal forest begin to close in.

Griffin’s storytelling is both gritty and hauntingly lyrical, steeped in the eerie beauty of the natural world and the spiritual unease that lingers in places of violence and greed. When O’Brien crosses paths with the enigmatic Nail sisters, Lucy and Lily, he becomes entangled in their secrets. The disappearance of Lucy sets him on a chilling path that blurs the line between the human and the supernatural. In this stark, snowbound landscape, myths breathe and monsters may walk among men.

Known for her evocative portrayals of northern life and the environment, Brit Griffin brings depth and atmosphere to every page. The Haunting of Modesto O’Brien is a tale of obsession, loss, and the haunting power of the land itself. With unforgettable characters and prose that burns with intensity, Griffin delivers a story that will stay with readers long after the final page, a testament to how the past can echo through both wilderness and soul.

Check out our Storytellers Fiction Interview with the author right here on Open Book!

Open Book:

Which authors have inspired you and/or influenced your work?

Brit Griffin:

Early on in my reading life I came across Lilith by Scottish writer George MacDonald (1895) in a free book exchange at a local mall. (It serves as a reminder to never be shy about leaving good books out and about to be discovered!) The book is a fantasy-style story—MacDonald influenced C.S. Lewis—a bit overwrought for modern reading tastes, but full of compelling archetypes, hauntings, and dark dreams.

One of the characters, a ghost librarian who is also a raven, loosened up my ideas about who has a voice, and raised questions about how immutable our physical human form actually is—all good inputs for an emerging gothic imagination. Later on, the work of the Latin American magic realists was very formative in my understanding of what writing could be, with writers such as Márquez and Allende pushing against all kinds of norms of the possible.

OB:

Do you see your writing style or philosophy reflected in a specific literary lineage, or branch of literature?

BG:

Reading Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude showed me that real/magic and rational/irrational can tumble together in literature—and that often they tumble together in real life too. That was freeing for me.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

Also, the role of myth and traditional stories in the writing, and the impact of a colonial past on the literary imagination, all resonated with me as someone of Irish descent but Canadian-born. The place of writing—the land itself—is more complicated though. Latin American magic realism was generated from an incredibly lush, diverse, and fabulous landscape.

The landscape that I write from is harsher, less colourful, more extreme; there is almost a tightness or meagerness to it. So, the struggle in my writing is to find the voices and stories that make sense here, and make sense in an imaginative lineage that is appropriate for me as someone who is not of/from the landscape on which I live, but who is trying to live with it in a respectful and just way.

OB:

What new voices excite you at the moment?

BG:

Max Liboiron’s (Métis/Michif, they/them) book Pollution is Colonialism (Duke University Press, 2021) stretched my mind, took frameworks, words, and knowledges that I had instinctually mistrusted and showed me why I was resisting them.

Much of my fiction writing is generated from the place where nature meets storytelling meets science/magic. Liboiron, a Professor of Geography at Memorial University (Nfld), offers feminist and anti-colonial approaches to understanding science, land relations, and the consumption/waste cycle—approaches that are radically helpful in navigating this place of exploration.

Also thought-shifting is their approach to research and writing, and their thinking around ideas like how to have “good relations within a text.” It is a monumental book—very exciting and energizing.

OB:

Do you draw from family or community stories in your work? If so, how?

BG:

The place I live is a post-industrial landscape, the remnant of a silver mining boom town from the early 20th century. It was a place of extreme events—of population moving, land destroying, peoples and creatures displacing.

The history of this place, and how we have told the story of this history at different times, is fascinating. Regardless of the various interpretations of what happened—ranging from a celebration of the adventurous capitalist through to environmental devastation—this small place has given rise to big, enduring, and fabulous stories. The local community is committed to, and interested in, its own history.

In a very real sense, its history persists, continues to haunt the landscape. So, these local stories and lore are compelling—they cannot help but appear in my writing. So far, all four books I have written have been located in this town. And so far, it seems like my next one will be too.

OB:

What are some other forms of storytelling that inspire you, outside of traditional novel-length work or short fiction?

BG:

During the writing of The Haunting of Modesto O’Brien, I read a lot of Irish myth and traditional stories, and it certainly pulled at the edges of my imagination, sent me off in strange directions. But the interesting thing about myth is how enduring and relevant they are—so as peculiar as many of the stories are, they still provide a structure to think about current struggles and moral dilemmas. I can see myself returning to these myths again and again in my writing.

OB:

What is the next story you’re working on, whatever form it may take?

BG:

I am in the embryonic stage of work on a novella/novel about changelings and sins against nature. I have met or imagined a couple of the characters so far and have caught a few glimpses into their world, and I think there is a good story there to tell. I am excited to get working on it.

The story seems like it will enable me to think further about the nature of our relationship with the non-human world—about pathways to atonement, which is something that preoccupies me both in my writing and day-to-day life.

_____________________________________

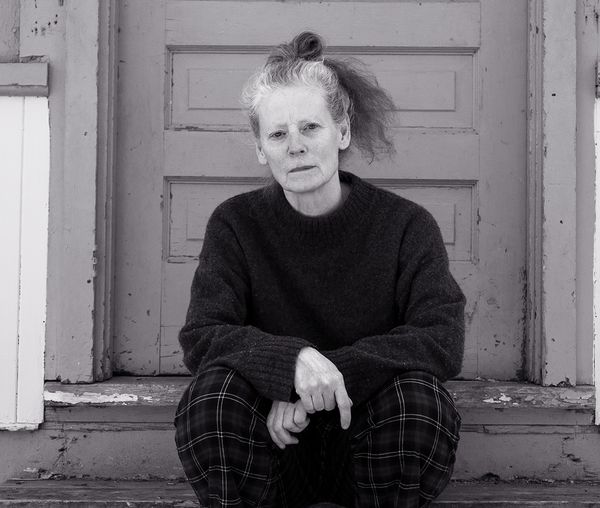

Brit Griffin is the author of the climate-fiction Wintermen trilogy (Latitude 46) and has written essays, musings, and articles for various publications. Griffin spent many years as a researcher for the Timiskaming First Nation, an Algonquin community in northern Quebec. She lives in Cobalt, northern Ontario, where she is the mother of three grown daughters. These days, she divides her time between writing and caring for her unruly yard.