Carl Watts on Why Poetry's So-Called Shortcomings Might Be Its Greatest Strengths

It's easy to imagine the scene: at a poetry reading (pre-pandemic), an open mic-er ascends to the stage, taps the microphone, and announces with aplomb, "I just wrote this five minutes ago." Cue the silent groaning in the crowd.

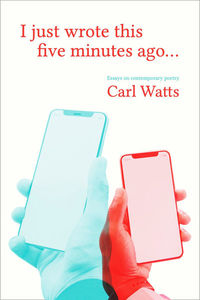

But in the cheekily titled I Just Wrote This Five Minutes Ago (Gordon Hill Press), the first book of literary criticism from poet and academic Carl Watts, Watts explores the idea that everything the poetry scene is sometimes knocked for (lack of profile, prestige, or professionalism), are exactly what makes it vibrant, accessible, and able to resist a capitalistic value system.

Watts speaks with us today about I Just Wrote This Five Minutes Ago as part of our True Story nonfiction interview series, telling us about what it is like to really delve into – and resist – the idea that "poetry is useless", explaining why it's helpful for a writer to have friends outside of the arts and humanities when writing projects get tough, and discussing the book by a nonfiction icon that has been incredibly important to him.

Open Book:

Is there a question that is central to your book? And if so, is it the same question you were thinking about when you started writing or did it change during the writing process?

Carl Watts:

Near the beginning of the book, I explore the popular notion that poetry is useless, or “makes nothing happen.” So there’s a central, kind of irresolvable question about what poetry is and does, especially as it is practiced and read today in Canada and the US. I think it’s a type of work, in a practical sense but without being competitive, or involving monetary value, or being strictly didactic or political or instrumental, i.e. a way of networking. It exists at the intersections of all those things without really being any of them, and that in itself is a form of usefulness. The argument itself is meant to be open-ended, maybe even a bit mushy (in both senses of the word). So yes, the question and premise shifted a bit during the writing process. That’s meant to reflect the form itself. The book is meant as an answer to the question of poetry’s uselessness, but of course the question remains.

OB:

Did you write this book in the order it appears for readers? If not, how did it come together during the writing process?

CW:

Absolutely not. Nowhere near! It was suggested to me that I write a unified book of poetry criticism. Because my current job has a heavy workload, and likely also because I’m a scatterbrained person, the approach I took was to expand some fragments I’d previously written that I found myself still thinking about—some readings of specific poetry books I had done in book reviews, and, surprisingly to me, several academic conference presentations I gave during my PhD but didn’t end up doing anything else with. Then, I worked out some completely new essays I wanted to write that were within the scope of the project. I had separate files for each of the chapters, and I was piecing them all together and trying to construct the introduction as I went. The essay that follows the introduction, about work, value, and the political understandings of poetry one encounters, also came about this way. That’s how it all got written, and then Shane Neilson, Gordon Hill’s editor, came up with the idea to separate the book into two sections (and re-sequence it pretty radically beyond that). So now it starts with my attempts at making a systematic argument and ends with globalization (and its possible end, as encapsulated in my doomed January 2020 trip to Thailand) and poetry as the realm of cultural hybridity and losers, but maybe the positive version of this.

OB:

What do you need in order to write – in terms of space, food, rituals, writing instruments?

CW:

In the before times, I did a lot of writing at libraries and cafes. The pandemic has been hard for a lot of people, I think, because many, myself included, can be much more productive when they can change locations and have a kind of social energy around them. I became really interested in libraries—public and university—and at some point started keeping a list of the ones I’ve done work in. A lot of my writing and research gets done in those settings. I’ve been living in Hamilton for the past couple years because it’s still not really viable to return to mainland China, where I work. When things were shut down it was hard to maintain a routine. More recently, it’s been better. While I haven’t been going out as much as I used to, there are a few places I go in the city that seem COVID-safe. A lot of the book was written at The Brain, for example, on James St. North, and I’m back at a couple locations of the public library.

OB:

What do you do if you're feeling discouraged during the writing process? Do you have a method of coping with the difficult points in your projects?

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

CW:

I’m probably not the best person in the world to give advice about this. If I’m stuck on something, an idea might come to me when I’m running or on a long walk while running errands or something. There’s one thing that’s started to help me recently—for better or worse, very few of my close friends work in the arts or humanities. So if I want to explain to them what I’m working on, I often have to render it in terms that a normal person would use while also making it seem like a real thing (rather than pure abstraction, theory, etc.). When I’m struggling with the nuts and bolts of a scholarly work or something like it, I try to think of it and outline it in those terms. It’s an exercise I’ve been having some of my students do lately, too.

OB:

What defines a great work of nonfiction, in your opinion? Tell us about one or two books you consider to be truly great books.

CW:

Nonfiction is, as far as I understand, a weird and fairly recent term. It denotes a kind of literary miscellany that, at least in Canada, was previously referred to as Biography? At any rate, it makes sense to me that lots of the nonfiction I’ve loved dwells in between a few subgenres. How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States, by Daniel Immerwahr, is something I talk about near the end of the book. It’s that evasive gold standard—a peer-reviewed, scholarly work that is actually appealing to a nonspecialist readership. It’s interesting, informative, and not bogged down by overly complex, gatekeeping academic language. That’s probably why, near the conclusion, he ties together so many disparate things without losing sight of the specifics, i.e., the larger conclusions are built from documented things that occurred on the ground. By the same token, Joan Didion’s Where I Was From is a blend of memoir, journalism, maybe even criticism, but it reads to me almost like fiction. It was a very important book for me; it changed my thinking about a lot of things, especially social class and how the built environments in which we grow up are arranged in a certain way for reasons, and that those reasons and our experiences in those places shape us in important, often insidious ways. Maybe only a hybrid book like Didion’s could get those points across.

OB:

What are you working on now?

CW:

I have to publish scholarly literary criticism as part of my job, so that’s always on my desk. I also love reviewing books, contemporary poetry especially, even though that’s arguably not the best use of my time. I have a poetry manuscript called Jock Jams that I’m always adding to and subtracting from, and that’s nearing some new threshold of completeness. When I had a lighter workload, I was piecing together a romance novel called The Genius. But I haven’t had as much time for that lately.

___________________________________________

Carl Watts is from Hamilton, Ontario. He holds a PhD in English from Queen’s University, where he wrote a dissertation about evolving conceptions of nationalism and ethnicity in twentieth-century Canadian fiction written in English. He has taught literature at Queen’s, Royal Military College, and Huazhong University of Science and Technology, in mainland China. His articles, book reviews, and poems have appeared in various Canadian, American, and British journals. He has published two poetry chapbooks, Reissue (Frog Hollow, 2016) and Originals (Anstruther, 2020), as well as a short monograph, Oblique Identity: Form and Whiteness in Recent Canadian Poetry (Frog Hollow, 2019). His more recent research interests include poetry subcultures, poetry anthologies, travel writing, expat communities, and addiction. His debut full-length collection of critical essays, I Just Wrote This Five Minutes Ago, is forthcoming from Gordon Hill Press in Spring of 2022.