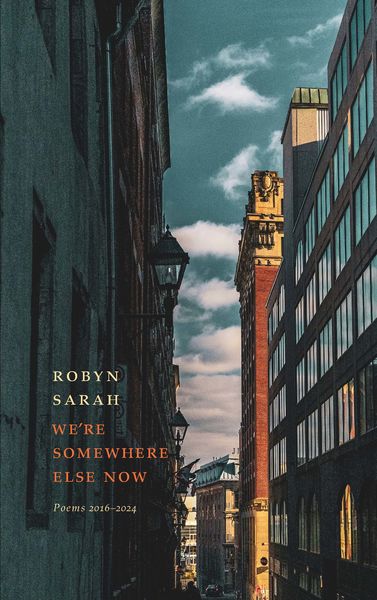

Celebrated Poet Robyn Sarah Returns After a Decade with a Brand New Collection, WE'RE SOMEWHERE ELSE NOW

Today on Open Book, we're featuring the new poetry collection, We’re Somewhere Else Now: Poems 2016–2024 (Biblioasis). This is a triumphant return from Robyn Sarah, and her first book of new poems in a decade. With her characteristic quiet wisdom, Sarah turns her attention to the pandemic years, capturing both the strangeness of isolation of that period, and the subtle beauty that persists in daily life.

These poems move fluidly between the intimate and the universal, chronicling grief, change, and moments of awe. Whether observing the calls of birds, a grandchild at play, or the passage of time marked by leap years, Sarah invites readers into a contemplative space—what she calls moving from “lit room to lit room.” Each poem is a reminder of what endures, even in uncertain times.

Several poems from the collection, first appearing in The New Quarterly, have already earned enthusiastic recognition, including nominations for a 2025 National Magazine Award in Poetry.

Open Book is delighted to share this Line & Lyric interview with the author, where she reflects on her writing process, her latest work, and what it means to write through a time of upheaval.

Open Book:

Can you tell us a bit about how you chose your title? If it’s a title of one of the poems, how does that piece fit into the collection? If it’s not a poem title, how does it encapsulate the collection as a whole?

Robyn Sarah:

My poetry book titles often do reference one poem, or a phrase taken from a poem, but the title for this one came to me differently. We were on the highway on our way to visit friends in the country – this was in 2022 – following the prompts of an outdated GPS and an emailed scan of a hand-drawn map. We hit a maze of blocked lanes and orange construction cones, and my husband took what soon appeared to have been a wrong path between them: where we came out, the place names we’d been seeing had changed.

“Is this the same highway?” I asked. “Where’s our exit sign?” The reply was a matter-of-fact “We’re somewhere else now,” and it struck me at once that this blunt statement of situational recognition would make the perfect title for the book I was working on. It summed up in four words what I had been feeling since February-March 2020, when we first got wind of a new virus out of China and watched the whole world shut down virtually overnight in response to it. The surreality was peaking in 2022, but I remembered how, from the very beginning, every morning I’d wake anew to the heart-sinking thought that the world as we’d known it had changed beyond recall and that there was no way it would ever go back to the way it had been before. (A friend to whom I told this story remarked wryly that “Where’s our exit sign?” would also make a good title.)

OB:

Did you write poems individually and begin assembling this collection from stand-alone pieces, or did you write with a view to putting together a collection from the beginning?

RS:

Both. I always write poems individually as stand-alone pieces, and it is always with the intention of eventually gathering the ones I think worth sharing, for publication as a collection. The poems accrue slowly and reflect my concerns and preoccupations over the period in which they’re written – a particular moment in history, experienced at a particular time in my life. This gives each collection a natural thematic unity, but I don’t consciously aim to create “theme” collections on pre-chosen subjects. (Jacket copy notwithstanding, I did not set out to “chronicle the pandemic years” in this collection; those just happened to be the years I was living when the larger number of the poems were written.)

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

With this collection, however, even as I continued to write individual shorter poems, I was working simultaneously on a single long poem, a philosophical meditation in a mix of poetic modes, that took a chosen subject as its point of departure: namely, the subject of doubt, at a time when the relentless advance of technology was pulling the underpinnings of received knowledge out from under us as a species. In the Wilderness, as I eventually titled this piece, evolved from a series of fragments that accrued slowly and separately, some in verse lines and some in prose, in parallel with the body of stand-alone poems.

These grew almost organically, in stages, into segments of a continuous text that became Part Two of the collection. The book’s two sections, as I began to realize, were counterparts, covering some of the same territory in different ways, echoing or reflecting off each other. This dual focus, sustained over a period of years, was the most surprising aspect of working on We’re Somewhere Else Now.

OB:

Apart from your editor and other publishing staff, who were the most instrumental people in the life cycle of this book? Did you share your writing with anyone while working on these poems?

RS:

I rarely share a poem or manuscript while it is still in progress, but I did ask two friends and trusted readers for input on the earliest finished draft of In the Wilderness, because it was so different from anything I’d attempted before as a poet that it was hard for me to judge what I’d written.

Marc Plourde is a Montreal fellow poet, translator of revered Quebecois poet Gaston Miron; we’ve known each other since the early 1980s. Joan Eichner was a close friend and editorial assistant to Margaret Avison, and became Avison’s literary executor. I had corresponded with Margaret for the last three years of her life, and I consulted extensively with Joan by email in 2010 when selecting poems for The Essential Margaret Avison; our exchanges, that began with our shared love of Margaret’s poetry, have continued since.

Marc and Joan each gave the first version of the long poem a close reading – two quite different readings, both insightful in ways that energized and reassured me. Their thoughtful engagement saw me through the necessary fine-tunings to bring out the poem’s true shape.

OB:

What's more important in your opinion: the way a poem opens or the way it ends?

RS:

The way a poem opens is crucially important. So is the way a poem ends. And everything in between is also really important!

OB:

What were you reading while writing this collection?

RS:

During the covid lockdowns, my husband and I returned to a habit of reading aloud that dates back to our early years together. Back then, we took turns reading, but this time I read and he listened (with occasional interjections: he had never read Anna Karenina before, and in an early scene in which Vronsky appeared, he remarked, “This guy is bad news” – later to opine that Tolstoy should kill him off before he made trouble). We read every morning after breakfast, over a second cup of coffee, and then we’d sit on awhile and talk about the day's selection.

We chose books from our own shelves, mostly not by living writers – rather, classics we'd read when younger and wanted to revisit, or books we’d always intended to read but hadn't: fiction, essays, biographies, autobiographies, memoirs. They spanned the end of the nineteenth century to the 1970s. Many were in translation (mostly from Russian, some from German, French, or Hebrew.)

These were not short books. We read almost all of Tolstoy. We read Dostoevski’s Brothers Karamazov and The Idiot. We read Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain. Collectively, they provided an often amazing retrospective of issues and ideas we are still debating urgently today, as if our own generation were the first ever to have thought about them.

OB:

Who did you dedicate the collection to and why?

RS:

The dedication page reads “for my generation”. Loosely speaking, that is the post-war, baby-boom generation, now facing an unfathomable future while negotiating a present marked by rapidly escalating technological change that our species set in motion and has all but lost control of.

As our parents pass on, we will soon be the last generation to remember a world before the escalation began – a pre-digital human landscape – before home PCs, before internet and cyberspace, before cellphones, social media, and “connectivity.” I guess I feel a certain tenderness towards us and our largely silent guardianship of that lost world remembered.

OB:

Is there an individual, specific speaker in any of these poems (whether yourself or a character)? Tell us a little about the perspective from which the poems are spoken.

RS:

If there’s an “I” speaker in a stand-alone poem, it’s nearly always “the author,” i.e. myself. But In the Wilderness is spoken by an “I” who is not exactly myself – a composite persona, sometimes myself, but sometimes an enactment of a human soul in our time.

It's a lone voice thinking aloud, an ad-lib soliloquy in something meant to approximate real time, trying to negotiate the smoke, noise, and confusions swirling around us as it casts for "something that will hold."

OB:

Was there a question or questions that you were exploring, consciously from the beginning or unconsciously and which became clear to you later, in this collection?

RS:

Many questions. The same ones I've been exploring since I began publishing. But I think they all boil down to: What does it mean to be human, existing in time?

OB:

For you, is form freedom or constraint in poetry?

RS:

It’s both at once. The constraint of working in a form means you can’t always say exactly what you want, or not in the words that come spontaneously to mind. The necessity to rhyme, to keep to a metre, to end a line with a given word, to begin or end a stanza with a given line, to find a synonym when the word you want has the accent on the wrong syllable (or if you can’t find one, to give up what you had intended to say and find something else to say in its place)... these restrictions, paradoxically, are liberating.

They show you that you don’t have to say what you first set out to say. They can free you to say things you would never come out with in free verse, things you wouldn’t otherwise allow yourself to express – powerful emotions, unconventional thoughts. In some mysterious way, the formal structure gives you permission to voice them.

_________________________________________

Poet, writer, literary editor, and musician, Robyn Sarah has lived in Montreal since early childhood. Her writing began to appear in Canadian literary magazines in the 1970s while she completed studies at McGill University and the Conservatoire de musique du Québec. Her tenth poetry collection, My Shoes Are Killing Me, won the Governor General’s Award in 2015. As well, she has published two collections of short stories, a book of essays on poetry, and a memoir, Music, Late and Soon (2021), that interweaves her youth as a professional-track clarinetist with her return at fifty-nine (after a lapse of thirty-five years) to the piano teacher who was her life mentor. From 2010 until 2020 she served as poetry editor for Cormorant Books.