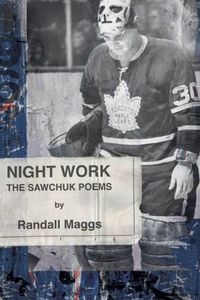

Celebrating the 10th Anniversary of Randall Maggs' Award Winning Night Work, Honouring Goalie Terry Sawchuk

It's been ten years since the original publication of Randall Maggs' Night Work: The Sawchuk Poems (Brick Books). At the time, the collection swept up countless awards and honours, including the Winterset Award, E.J. Pratt Poetry Prize, Kozbar Award, and more. The poems tell the story of Terry Sawchuk, the genius but complicated goalie who played 21 seasons in the NHL and went on to be named amongst the 100 greatest NHL players in history. At the time of his death, Sawchuk held the all-time wins record for an NHL goalie.

This year, Brick Books has released a 10th anniversary edition Night Work that marks both the 50th anniversary of the last time the Leafs won the Stanley Cup and the 100th anniversary of the Leafs (who Sawchuk played for, amongst others) as a team. The new edition includes essays by Hockey Night in Canada host Ron MacLean and author Angie Abdou, as well as excerpted reviews of the collection from Gord Downie, Dave Bidini, and others. It's a true love letter to an unforgettable figure in our national pastime. The collection is also illustrated with photographs mirroring the text, which delves deeply into the violence Sawchuk experienced in the Original Six era, his own personal - and sometimes controversial - intensity, and his astonishing accomplishments.

We're proud to present an excerpt from Night Work on Open Book today, as well as recordings of Maggs himself reading from the collection, both courtesy of Brick Books.

_______________________________________

Three Poems from the 10th Anniversary Edition of Night Work: The Sawchuk Poems by Randall Maggs:

DESPERATE MOVES

“The greatest save I ever saw

in hockey,” says Plante, waving pages of notes

in his trapper hand, the black suit too tight and the tie

too narrow, emphasizing an angular face and a startling

inelegant sprawl as he tries in his chair to show Ward Cornell

just how Sawchuk, flat on his back in a pileup

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

in front, puts a pad high in the air

to save the game,

as Terry himself turns up. He’s come

straight from the ice in his gear for a rare interview,

easing himself and his leaden pads towards an awkward chair.

Cables, tables, precarious lights. Disaster a stumble away,

he knows about that.

He’s careful too with Plante’s enthusiasm,

shrugs off the compliments—the guys were clearing

rebounds, the forwards picking up their man.

Asked about the save, he looks away,

“I stuck up a leg,” as if to say like anyone would.

“He puts one on the ice it’s in. You know yourself,

Jacques, it’s better to be lucky than good.”

Plante resists a cozy acquiescence like a monk.

He seems too open, too unguarded for a goalie. The heart

of matters is what he wants to wade into, but this is Hockey Night

in English Canada. His catching hand comes up to make

a point, to ask about the sudden drop in weight,

over 200 pounds to 165 in a year, the trade, the brutal

Boston press, the train in the night to Detroit. But Terry

steers the questions off into a corner. “You do what you have

to do. You know I’ve always admired you, Jacques,

down at the other end.”

Plante sits back, unsatisfied, and Ward murmurs

something inert about grit or momentum.

You see the goaltenders glance at one another,

the only moment in the interview that their eyes meet.

The silent exchange is arresting.

They know each other’s subtlest movements

in their sleep, but they’re not accustomed to being

so close. You wonder what they might have said

to one another, left alone, but up this close

it’s better to keep side-on.

That’s the message from Terry at least.

“So when you saw Keon wide open,” says Plante,

“what you made was a desperate move.”

“That’s it, Jacques,” Sawchuk says, all in one motion

detaching his mike and rising up out of the ill-considered chair,

“that’s all it was.”

*

ONE OF YOU

Catchers in baseball, closest to cousins

in your differentness, the safeguarding home, the healing bones,

the serious gear (which ought to indicate the possibilities),

and only one of you.

Denied the leap and dash up the ice,

what goalies know is side to side, an inwardness of monk

and cell. They scrape. They sweep. Their eyes are elsewhere

as they contemplate their narrow place. Like saints, they pray for nothing,

which brings grace. Off-days, what they want is space. They sit apart

in bars. They know the length of streets in twenty cities.

But it’s their saving sense of irony that further

isolates them as it saves.

Percy H. LeSueur, for one, in a fitful sleep,

flinching at rising shots in a bad light, rubbers flung

out of the crowd, insults in two languages, finally got out of bed

in a moment of bleak insight, went down and burnt a motto

onto his stick, Haec est manus quae ictum deflecit—

“This is the hand that turns away the blow.”

Or Lorne Chabot, in 1928, when someone asked

him why he always took the trouble to shave before a game,

angled out a leg to check a strap and answered in a quiet voice,

“I stitch better when my skin is smooth.”

Or dapper Charlie Rayner, who stopped a bullet

with his chin, another couple of teeth and some hasty

work to close an ugly cut. Back the next night, he takes another,

full in the face. A second night in a row, he’s down, spitting

bits of tooth to the ice. “It’s a wonder,” he mutters,

“why somebody doesn’t get hurt in this game.”

*

THE FAMOUS CROUCH

A fierce moon at the window hunting boys.

An attic room my brother shared with me, the good warmth

diving under quilts on winter nights, four steps

from the bucket to the bed.

And laughing in the dark at how old goalies

held their sticks, all knuckled up, and how they combed their hair.

I'd tell Mitch that he was mental playing goal,

but always helped to scrape the ice before he played.

Then stamp a flat spot on the bank behind him, changing ends

when he changed ends. "Terry, keep your fingers off the screen,"

he'd warn me, once he'd kicked the puck away.

He clasped his hands behind his head (they said),

behind his desk at work that day and stretched and yawned,

content (he'd shut out St Vitale the night before and he'd seen

Corinne Wynick in the crowd), and smiling, cocked

his head to make a final point (they said),

half-rose and then pitched forward on his face.

All those nights I'd hear him

in his sleep. Stay low, stay forward, balance

on a ball. Forget the names they sing you through the screen.

See the shot before it leaves the stick.

Such preparedness, I'd lie awake and think.

And so I got accustomed to the view from here.

You watch them come at you in waves

and watch them fly away. In my dreams he plunges

after the puck, then turns to find me grabbing at the screen.

But now it's me who's bending low and looking for

the bullet shot. All my life, I'd heard the warning

in his voice and in the moment's heat

I hear it yet.

*

If you're looking for even more Sawchuk-centric goodness, check out this short film based on Maggs' collection.

Congratulations to Brick Books and Randall Maggs on the 10th anniversary of this indelible, and quintessentially Canadian, contribution to the CanLit landscape.

_______________________________________

Randall Maggs is the author of the poetry collection Timely Departures (Breakwater Books, 1994), and co-editor of two anthologies pairing Newfoundland and Canadian poems with those of Ireland. He is one of the organizers and the former artistic director of Newfoundland's March Hare, the largest literary festival in Atlantic Canada. He is a former professor of literature at Sir Wilfred Grenfell College, Memorial University. Night Work: The Sawchuk Poems, his second poetry collection (Brick Books, 2008), was the winner of the 2008 Winterset Award, the 2009 E.J. Pratt Poetry Prize, and the 2010 Kobzar Literary Award, and was shortlisted for the 2009 Heritage and History Book Award, longlisted for the Relit Award and named a Globe 100 book in 2008. He lives in Steady Brook, near Corner Brook, Newfoundland.