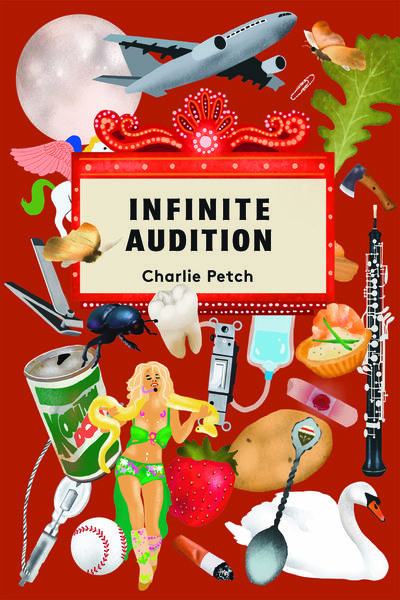

Charlie Petch's INFINITE AUDITION is an Unpredictable, Theatrical Poetic Tour de Force

Our featured title today comes from Charlie Petch, a celebrated artist who explores transmasculine and disabled perspectives in their writing. Their work invites readers to engage with art that refuses to separate vulnerability from strength and celebrates performance as possibility. The author is back with a brand new poetry collection, which is unsurprisingly daring and immersive.

In Infinite Audition (Brick Books), Petch pushes spoken word poetry to its outer edges. Its sections move from solo performance to musical and dance collaborations, even into puppetry, and also monologues and audition pieces crafted for trans and non-binary performers. Each poem opens a tiny, surprising universe; sometimes voiced by a hotel room, sometimes by a closet, a mythic creature, or even body parts on a night out. The only thing readers can be sure of is to that they'll be constantly enthralled.

The author's theatrical and operatic imagination infuses every piece with humour, bravery and emotional resonance. Their work invites readers to embrace unpredictability and to explore the full expressive range of performance on the page.

Check out our Poetry in Perspective interview with the author, where they talk about this very exciting new collection!

Open Book:

In your eyes, what impact does poetry have on the world?

Charlie Petch:

I’ve heard the saying that a good poet doesn’t lie, and in the world today that honesty feels urgent. Contemporary poetry has become deeply anti capitalist. It reminds us that meaning isn’t tied to money, that simple acts can hold beauty, and that listening and observing are acts of love. At its core, poetry honours presence and protects the importance of dreaming.

I come from spoken word, which is even more directly anti capitalist because it belongs to the people. It doesn’t need academic training or even a written page. Spoken word grows from oral traditions, influenced by Indigenous and hip hop cultures, and celebrates those roots. When we write from that lineage, we acknowledge our responsibility to decolonize for a better future. It’s no accident that so many Poet Laureates today come from spoken word as the world heats up and fascism rises.

OB:

What role do you think poetry plays as a reflection of the world or the societies that we live in?

CP:

Poetry is everywhere. It shows up in political speeches, memes, bathroom walls, and protest signs. It’s a hum running through our culture. Today’s poetry feels like flowers pushing through cracked concrete — appearing where no one invited it, but flourishing anyway. Poetry is hope, and hope fuels every revolution.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

We’re watching our neighbours fall into fascism and white supremacy, and we’re seeing governments restrict books that threaten those systems. Here in Canada, especially in Alberta, the far right is rising as well. Words like “terrorist” are being weaponized, and people are jailed for peaceful protest in a world addicted to its screens. Poetry feels like an antidote. Poets aren’t shaped by the logic of profit, so we can reflect the people’s voice more freely. I’m seeing more trans poets, more BIPOC poets, and more audiences eager for representation. Poetry has always been present, but now, thanks to the internet, spoken word is everywhere because it fits today’s attention span.

OB:

How has your poetry developed or evolved from work to work?

CP:

I’ve always worked across disciplines. I started with short stories, poetry, and plays in Peterborough/Nogojiwanong. My early chapbooks were written under the name Tits McGee, a character I created while hosting a lesbian and trans rock band. Those books were bawdy and hilarious, and looking back, they were a way of coping with living in a body that felt wrong.

Publishing Late Night Knife Fights with Luciano Iacobelli’s LyricalMyrical Press bridged those early tones with the voice I was growing into. Around then, I found slam poetry, which felt like the perfect monologue form for someone who’s also a playwright. I entered that world deeply wounded after a divorce, and the slam community held and healed me — even through my husband’s death.

As I grew, I brought musical saw and other instruments into my sets. I wanted to return to theatre, which lets me bring all my disciplines together. I wrote a show intentionally rooted in spoken word, released an album as a kind of radio play, and eventually transitioned. My play transitioned with me — I rewrote its ending once I truly saw myself.

Transition changes your understanding of your entire life. My first Brick Book helped me embrace masculinity while holding it accountable for harm and the messages men receive about belonging. It launched during lockdown, while I was undergoing surgeries — only one of them gender affirming. Healing has defined my life since 2013.

It might sound strange, but it feels like I’m only now becoming the artist I am. Before, my body was always in the way. My most recent book gathers the shows I performed after coming out. My goal now is to make as much work as possible before governments try to burn our stories again. I want trans kids to find my writing and know there’s a guy who feels what they feel, that being trans is not only normal but an exceptional way to exist.

OB:

Is the world of poetry more exciting now than it has been in the past? In what ways?

CP:

The poetry slam movement has changed everything. In a world of constant scrolling, these short bursts of wisdom really land. While slam as competition is relatively new, spoken word has been with us since the beginning. The internet pushed it forward alongside anti racist movements, #MeToo, #LandBack, and other decolonizing work.

Because I also work in theatre and music, I can say that spoken word was the first space where I saw real time decolonization efforts as an artistic expectation. We had hard conversations with our community and audiences, made mistakes, grew, were humbled, and learned how to call each other in rather than only call out. There’s still much further to go.

Poets have taught me, and many others, to value our collective histories and to bring politics into practice. I’m seeing more spoken word in CanLit, more conversations about representation and anti racist curation, and more disabled, trans, non binary, and Two Spirit poets being platformed. I found out who I am through this community, and learned how to be the best man I can be among people unafraid to speak up.

The internet gave access to voices that had never been heard so widely. Communities organized. Trans, non binary, and Two Spirit people found one another. Black Lives Matter took flight. White supremacy was called out. Minds opened. And the poets were there to interpret the chaos, hold ancestral dreams, and ask for more than anyone imagined.

OB:

What are you working on now, and how would you like it to challenge and affect readers?

CP:

My next manuscript is about life after top surgery. Nothing could have prepared me for what this surgery did for my psyche and my ability to exist as something other than an apology.

As an older trans man, I know many people my age are struggling to come out in ways that will change how others see them. Our sex education was deeply straight or framed around AIDS panic. There were no queer groups, no GSAs. Many are staying silent because they don’t want to lose their families. The fear and shame are overwhelming.

I want people to know that surgery can bring you home to yourself. I feel alive now in a way I never imagined possible. So much is working against us — from the lack of surgeons to the fear surrounding trans health care, to the way the world shifts around you when you change your body. If I’d had puberty blockers, I wouldn’t have needed the surgery that saved my life. Now society is asking us to go backwards. Writing about joy and proper health care feels revolutionary. It’s the book I needed when I was young.

I’m also working on an audio project, still in early stages, but rooted in shared experience — a kind of health care in itself. I had the typical life of a trans man born in the 70s: not knowing myself, surviving misinformation, and finding community late. Trans people are everywhere, and yet we’re being used as tools of the state to restrict bodily autonomy. Dispelling fear and sharing love feels like the best use of my platform in a world that asks us to disconnect to keep the economy running.

______________________________________

Charlie Petch (they/them, he/him) is a disabled/queer/transmasculine multidisciplinary artist who resides in Tkaronto/Toronto. A poet, playwright, librettist, musician, lighting designer, and host, Petch was the 2017 Poet of Honour for the speakNORTH national festival, winner of the Sheri-D Golden Beret Award from The League of Canadian Poets (2020), and founder of Hot Damn it’s a Queer Slam. Petch is a touring performer, as well as a mentor and workshop facilitator. Their debut poetry collection, Why I Was Late (Brick Books), won the 2022 ReLit Award, and was named “Best of 2021” by The Walrus. Their film with Opera QTO, Medusa’s Children, premiered 2022. They have been featured on the CBC’s Q, were the Writer In Residence for Berton House (2023), were long-listed for the CBC Poetry Prize in 2021. Their solo show “No one’s special at the hot dog cart” debuted at Theatre Passe Muraille in 2024.