Cheryl Thompson on the Complicated History of the Black Beauty Industry in Canada

The politics of Black hair can be deeply complex, and the industry surrounding Black beauty intersects with the cultural and personal experiencing of Black people, especially women. From the struggles of finding makeup in inclusive ranges to messages about hair texture in media, Black women face a beauty landscape that includes barriers both overt and subtle.

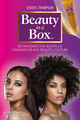

In Beauty in a Box: Detangling the Roots of Canada's Black Beauty Culture (Wilfrid Laurier University Press), academic Cheryl Thompson takes readers on a fascinating, intersectional journey through Black beauty culture via media advertisements and articles (including print, television, and more). She also explores the active role that local Black communities and Black-owned businesses and brands played and are playing in mainstreaming Black beauty products. Timely, thorough, and eye-opening, the book is an essential read, bringing together theories around consumerism, advertising, feminism, Black culture in Canada, and the politics of beauty.

We're very excited to welcome Dr. Thompson to Open Book to talk about Beauty in a Box through our Lucky Seven interview series. She tells us about the decision in her own beauty routine that prompted her to examine the cultural dynamics of Black beauty more closely, the Black Canadian newspapers that became essential sources in her research, and her secret to avoiding feeling discouraged during the writing process.

Open Book:

Tell us about your new book and how it came to be. What made you passionate about the subject matter you're exploring?

Cheryl Thompson:

My new book took me 10 years to write. It started as my PhD dissertation at McGill University in the fall of 2009. At that time, I wasn’t sure what the project would become, but as the years rolled on, and as I started doing extensive work in archives, I realized that I had uncovered so much information about Canada’s Black media history that the project would eventually become a book. It took several rounds of edits post-dissertation to get here, but it was worth the effort. My passion for the topic is personal. In 2007, I had transitioned from using a chemical hair straightener – known as a “relaxer” – to wearing my hair in dreadlocks, a natural hairstyle. This life change led to me to question why I had “relaxed” my hair for over fifteen years, and what it meant that now, in my 30s, I no longer did so. Beauty in a Box reflects both a personal interest to know the Black beauty culture industry that I was imbricated in for most of my adult life, but on a scholarly level, it reflects my determination to bring this never-before-told story to life.

OB:

Is there a question that is central to your book? And if so, is it the same question you were thinking about when you started writing or did it change during the writing process?

CT:

The central question my book explores is how did Canada’s Black beauty culture industry, which was literally non-existent prior to the 1970s, enter mainstream retail and the pages of local Black media? This question changed over time. Initially, I struggled with the question of how I was going to write a book about Black beauty in Canada, when there is so little known about Black history, especially in the time frame I was most interested in – pre-1960s. After doing extensive research in newspaper archives where I read through the entire collections of The West Indian News Observer (1967-69), Contrast (1969-1991), The Dawn of Tomorrow (1923-1971), The Clarion (1946-1956), and Share (1978 -), these Black Canadian newspapers provided a corpus, so to speak, of Black beauty articles, images, advertisements, and editorials. I then realized that the question of my book was as much about Black media as it was about Black beauty culture.

OB:

What was your research process like for this book? Did you encounter anything unexpected while you were researching?

CT:

My research process began with a literature review, which is typical of academic writing. I read every book there was to read on the topic of African American beauty culture. I then began to read through the literature on nineteenth-century slavery and emancipation; twentieth century Canadian immigration and migration; and consumer culture history, especially histories of advertising in magazines and newspapers. After this, I realized that if I was going to write a book on Black beauty culture, in general, I needed to travelled to archives in the U.S. to look at collections of historical African American beauty ads, Ebony (1945 –) and Essence (1970 –), as well as The Chicago Defender (1905 –), which was, for most of the twentieth century, one of the most influential African American newspapers in the country. Even though this might sound a bit melodramatic, everything about my project was unexpected. When I would go into archives and describe my project to an archivist in Canada, I was often met with a puzzled look and confusion as to how I was going to use anything in the collection to research my topic. This was often quite frustrating. When I worked in collections in the U.S., this was not my experience. So the process of researching this book was really trial and error, and listening to my gut when I had a hunch that a particular collection would provide me with some nugget of information about Black beauty culture in Canada and/or Black cultural history.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

OB:

What do you need in order to write – in terms of space, food, rituals, writing instruments?

CT:

I am one of those writers who need to be inspired to write. I cannot keep a set schedule and get up everyday and write, even if I don’t feel like it. I have to have that feeling, deep inside, that yes, today is the day to write. Often, if I sit down to write and know that I have to, i.e., I have a deadline approaching, I still won’t force it. I will do some cleaning, make something to eat, exercise, or whatever I need to do until that feeling starts to happen inside, and then I can sit down and start writing.

OB:

What do you do if you're feeling discouraged during the writing process? Do you have a method of coping with the difficult points in your projects?

CT:

Because I don’t force myself to write, I rarely feel discouraged. Writing is a process; it is not an exact science. I’m a process-oriented person so I know I’m in the right profession because writing has never been a struggle for me. I’ve always approached it like an artist approaches a canvas. The initial idea can be a bit challenging as you try to figure out how you want to approach whatever it is you’re writing about, and then second, how you want to express your thoughts, which will depend on the audience you’re writing for. But once you get through that initial hurdle, and the structure of the piece begins to take shape, it becomes an enjoyable process for me. I begin to realize that I’m saying something unique that I didn’t even know I would beforehand. The only difficult part of writing is editing. Thankfully, I’ve always had good editors around me, but going through their recommendations on revisions can often feel like a daunting endeavour. I’ve learned to take edits piece by piece, rather than on the whole, and it makes it psychologically easier to contend with them.

OB:

What defines a great work of nonfiction, in your opinion? Tell us about one or two books you consider to be truly great books.

CT:

A great work of nonfiction has to make me think about some aspect of my life and/or work differently. It has to move me in some way. I also appreciate works of nonfiction that are multi-layered, and multi-dimensional. bell hooks’ Black Looks: Race and Representation is still one of those books that I return to year after year. In fact, my copy has been read so much that the binding is completely falling apart and I have to keep it together with an elastic band. More recently, in the non-academic realm, when I read Iyanla Vanzant’s Peace From Broken Pieces: How to Get Through What You’re Going Through, it fundamentally changed my perspective on what I thought I couldn’t get through and what I knew I could get through. I read that book around the same time I finished my PhD. I had moved back to Toronto from Montreal, and I was unemployed, living on my sister’s couch. It helped me to keep applying for jobs and to also keep writing, even though I was not attached to a university. With the help of that book, I kept doing the thing that I enjoyed most, and it ultimately got me to where I am today.

OB:

What are you working on now?

CT:

I’m currently working on my next research project, which is an examination of Canada’s history of blackface minstrelsy and Black performance at the theatre. Specifically, this project aims to trace not only the history of Blackface at the legit theatre from the mid-nineteenth century through to the 1920s, I also aim to explore how blackface was performed as if a home-grown form of entertainment in local communities from the 1910s through the 1960s. This work extends research I did on the topic during a two-year Banting postdoctoral fellowship (2016-2018) I held at the University of Toronto in the Centre for Theatre, Drama and Performance Studies, and at the University of Toronto Mississauga’s Department of English & Drama. I am currently completing the last portion of the research on the history of Black choral performance at the theatre, specifically, the Fisk Jubilee Singers who toured Toronto for over twenty years in the nineteenth-century, and the lesser known history of Black Canadian choral singers, such as the O’Banyoun Jubilee Singers. Similar to my first book, this current research sits at the intersection of visual culture, media culture, and narratives of immigration, belonging, and anti-Black racism.

____________________________________

Cheryl Thompson is an Assistant Professor in the School of Creative Industries, Faculty of Communication and Design at Ryerson University. She previously held a Banting Postdoctoral Fellowship (2016-2018) at the University of Toronto. She earned her PhD in Communication Studies from McGill University. Dr. Thompson was born and raised in Toronto.