December Spotlight on Excerpts: Read About the Maple Leaf from Symbols of Canada

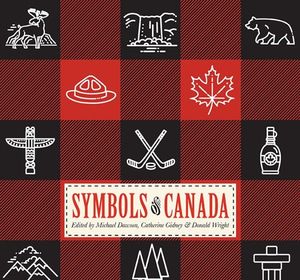

Symbols of Canada, edited by Michael Dawson, Catherine Gidney and Donald Wright (Between the Lines Books), delves into the titular symbols, whether they're as storied as Indigenous carvings or as feel-good as the Timbit, getting to the heart of the complex and evolving entity that is Canadian culture.

From Mounties to beavers to maple syrup, the essays in Symbols of Canada take as their starting points the seemingly benign images tied to the idea of "Canada" and intelligently question both their origins and the ways in which they - and their meaning - have changed over time. By turns surprising, contentious, entertaining, and informative, the book explores nearly 200 images and symbols.

Today, as part of our month-long spotlight on excerpts, we get to share an essay from Symbols of Canada - and an image - with you, courtesy of Between the Lines Books. It's one of the most iconic of all: our flag, also known as The Maple Leaf.

The Flag by Donald Wright, an excerpt from Symbols of Canada:

On 15 February 1965, the Red Ensign was lowered and the Maple Leaf was raised in a ceremony on Parliament Hill: after a divisive debate, Canada had a new flag. Relegated to the dustbin of history, almost no one today remembers the Red Ensign, but the Maple Leaf didn't unite the country either. As Pierre Trudeau said in 1964, Quebecers "do not give a tinker's damn about the flag." After all, Quebec had its own flag, the Fleurdelisé, adopted unanimously by the Legislative Assembly in 1948. In effect, then, if not in law, Canada has two national flags, one for Canada, the other for Quebec. Canada has two national anthems as well. For the most part, this works. But occasionally it doesn't.

In the lead up to Quebec's 1995 referendum on independence, which was too close to call, the Liberal government of Jean Chrétien wrapped itself in the Maple Leaf. Conveniently, 1995 also marked the flag’s thirtieth anniversary, giving the government a million-dollar opportunity, literally and figuratively, to celebrate a national milestone. It also gave MPs the opportunity to make earnest speeches, each more patriotic than the last. The Maple Leaf, said one MP, "stands for peace, harmony, and freedom"; another said that it "represents a wealthy and tolerant country that is open to others"; and yet another said that it symbolizes "compassion, sharing, and equity." One MP even told the House of Commons, without a hint of irony, that it "unites us from coast to coast," forgetting for a moment that Her Majesty's Loyal Opposition was the Bloc Québécois, a separatist party. Indeed, a Bloc MP questioned why the government had spent $1 million to celebrate the flag "in this era of budget cuts" and accused the government of launching "a vast federal propaganda campaign" in Quebec. A disingenuous heritage minister responded that he was doing no such thing, adding that "some people have a very narrow mind on these issues, so narrow that their ears are stuck together from the inside." The Speaker wisely ended the back-and-forth: "Sometimes these exchanges give me such a headache."

A near-death experience, the October 1995 referendum led the government to redouble its use of the Maple Leaf: Prime Minister Jean Chrétien proclaimed February 15 National Flag of Canada Day, or Flag Day for short; Heritage Minister Sheila Copps launched One In A Million, a campaign to give away one million flags in one year; and a Liberal MP tried, on two occasions, to get a private member's bill passed that would establish an oath of allegiance to the flag. One Bloc MP compared the government's use of the Maple Leaf to Joseph Goebbels' use of the swastika in Nazi Germany. It was a stupid thing to say, but another Bloc MP reminded the House that "our country is Quebec and two, three, or even four million flags cannot change the fact that Quebec will always be our country." Undeterred, the Chrétien government pimped the flag when it initiated a sponsorship program to promote Canada in Quebec: wherever Quebecers went and wherever they gathered, the Maple Leaf would be there. Unaccountable from the start, the sponsorship program ended in accusations of corruption, a commission of inquiry, and criminal charges against the key players. No politicians were ever charged and an unrepentant Chrétien shrugged the whole thing off, saying "there's nothing wrong with showing the flag."

The Conservative Party came to power on the heels of the sponsorship scandal, but it wasn't above flag politics. Refusing to concede patriotism in general, and the flag in particular, to the Liberals, Prime Minister Stephen Harper embraced Flag Day and, on the eve of the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver, urged Canadians to fly the flag. A year later, one of his backbenchers went further. Worried that the Maple Leaf couldn’t defend itself, John Carmichael introduced a private member's bill making it a crime, punishable by up to two years in prison, for a person to prevent another person from displaying the Canadian flag. As he told the House, this bill "represents an opportunity for us to stand behind those who wish to display our most important national symbol" but who are prevented from doing so by condominium boards, homeowner associations, and landlords.

An incredulous NDP MP from Quebec observed that the proposed National Flag of Canada Act was "eerily similar" to the 2006 Freedom to Display the American Flag Act, the brainchild of Roscoe Bartlett, then a Republican congressman, member of the Tea Party Caucus, and survivalist. Besides, the NDP member asked, is it "really necessary to turn a hapless caretaker, following through on a condo bylaw on behalf of a condo board, into a criminal?" The "last thing we want is the flag police," a Liberal MP added. Agreeing to remove the threat of prison, Carmichael insisted that it was "fundamentally wrong that people could intimidate, bully, or otherwise restrict Canadians from flying our flag." Supported by the Conservatives and the Liberals, but opposed by the New Democrats, over one-half of whom were from Quebec, Carmichael's bill became law in 2012. Because it only encourages, and does not compel, apartment buildings, co-ops, condominiums, and gated communities to allow the Canadian flag to be displayed, the National Flag of Canada Act is purely symbolic—like the flag itself.

To mark the flag's fiftieth anniversary in 2015, Senator James Cowan told his colleagues that although Lester Pearson "gave us" the Maple Leaf, it "goes beyond any government or leader"; it goes "beyond politics or policies"; indeed, it goes "beyond even history." Of course, flags are never outside of policies, politics, or history, something Emma Hassencahl-Perley understands. A Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet) visual artist from Tobique First Nation in New Brunswick, she covered the Maple Leaf with thin shreds of the Indian Act, transforming what former prime minister Paul Martin called “our most treasured national symbol” into a symbol of colonization and assimilation. Visible between pieces of the Indian Act is the colour red, the colour of Indigenous peoples, making White Flag a symbol of resistance and renewal as well: despite your best efforts, Canada, we are still here.

_______________________________________

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

Donald Wright is a professor of political science at the University of New Brunswick.