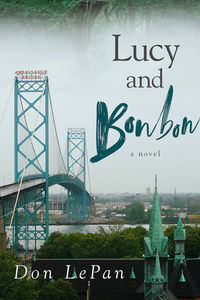

Don LePan on Exploring the Thin Divide Between Human & Non-Human in His Thought Provoking New Novel

The line between humans and other primates can seem, from an evolutionary standpoint, paper thin. Don LePan, in his new novel Lucy and Bonbon (Guernica Editions), goes beyond simply looking at genetic and behavioural similarities though and asks what might happen if the next step were possible; if humans and other great apes were in fact able to cross breed? What would the resulting primate—or, perhaps, person—act, think, and feel like? And how would human society react to such a being?

The chilling, fascinating answers LePan imagines in Lucy and Bonbon are a stunning mixture of near future sci-fi, family story, and social portrait. Anchored in the titular Lucy and her child Bonbon, the novel explores concepts of freedom, identity, love, and the very nature of what it means to be human.

LePan, who is also an acclaimed publisher and the founder of academic publishing house Broadview Press, is more than up to the monumental task he's set for himself as a writer in Lucy and Bonbon, with the novel earning praise from the likes of Richard Dawkins for its balance of ethical exploration and page-turning storytelling.

We're speaking with Don today about this riveting and unique book. He tells us about why borders (of all kinds) became important for the novel, about the "wonderful mystery" of writing—and connecting with—a character so different from himself, and why he dedicated his book to a parrot.

Open Book:

Do you remember how your first started this novel or the very first bit of writing you did for it?

Don LePan:

Maureen (my partner) and I were chatting over dinner, and somehow the topic of hybrids came up. She knows a good deal about science (as I don’t); she gave me a basic lesson on mules and hinnies and all sorts of hybrids. And the idea for a story began to take shape.

OB:

How did you choose the setting of your novel? What connection, if any, did you have to the setting when you began writing?

DL:

The novel is very largely about the line between the human and the non-human—or the lack thereof—and as the story took shape in my mind it seemed natural to have much of it take place at or near borders. Both before and after Lucinda gives birth she goes back and forth a good deal between Windsor and Detroit, and later on, as the end of the novel approaches, the setting is an Alberta river right at the Canada-US border. One of the scenes at the Ambassador Bridge (crossing the border in a vehicle with a canoe on top—a canoe stuffed with roped-in boxes of stuff—in the process of moving from Ontario to Alberta, feeling considerable anxiety as to whether the border guards will insist on having everything unpacked, and then tasking a wrong turn and getting lost in a dodgy neighbourhood in the wee hours of the morning) is something that happens to Lucy, and it’s something that happened to me as well. And I’ve spent quite a lot of time on Alberta rivers over the years.

OB:

Did the ending of your novel change at all through your drafts? If so, how?

DL:

At some point fairly well on in the process (certainly after I had completed the first draft), the thought came to me of having the climactic scene occur on the night that Donald Trump was elected. That changed the ending a certain amount, though the basics remained the same.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

OB:

Did you find yourself having a “favourite” amongst your characters? If so, who was it and why?

DL:

Lucy. More than once when I was writing about her, Lucinda really took over the writing process, and started writing about herself. And she can be very funny; a bunch of times she made me laugh out loud at what she did, or what she said.

How that sort of thing can happen in the creative process remains—to me at least—a wonderful mystery. Lucy could hardly be more different from me; she’s in her thirties and I’m well into my sixties; she’s working class and I’m not. She’s a woman, and I’m not. She drinks Bud, and I drink Canterbury Dark Mild. The list goes on.

I love Bonbon too, and I like Ashley a lot. But Lucy is my favorite.

OB:

If you had to describe your book in one sentence, what would you say?

DL:

The sentence would be a question: “What if there is no clear line between the human and the non-human?”

OB:

Did you do any specific research for this novel? Tell us a bit about that process.

DL:

The novel is about a hybrid created by the union of Lucy (who is a human being) and Bei, who is a bonzee. Bonzees are described in the novel as being very similar to bonobos; I wanted a species bearing a close resemblance to an existing species, but I also wanted a species that could exist in the realm of the imagination. Had I made Bei a bonobo, I would think that readers who know a fair bit of biology might continually have been distracted—“wait, would a bonobo act just like that in those circumstances?” they would be thinking.

As I say, though, I did want the bonzee species to bear a close resemblance to bonobos, and for that reason I did a certain amount of research into bonobo behavior. I also asked a couple of academics who are highly knowledgeable in relevant areas—the philosopher Peter Singer and the biologist Richard Dawkins—to read the manuscript. Both were kind enough to do so (and to comment very positively, which was a real plus!). And Singer in particular provided some detailed and very helpful suggestions. I can also credit Singer with pushing me to make the manuscript into a novel in the first place; he first read a version of what became the first couple of chapters back in 2012, when I had no idea of making the thing into anything more than a short story. He recommended that story version to The New Yorker (which of course didn’t publish it—probably wisely), but he also suggested that I extend it into a novel-length manuscript.

I did a bit of research into the geography of Detroit as well; I wanted to convey something of the feel of that city, and it’s not a city I know well. I should say, though, that, as with the biology of the novel, the geography of the novel exists in the realm of the imagination. In the novel, for example, the river that flows through southern Alberta’s largest city ends up flowing a long way south, over the border and into the United States.

OB:

Who did you dedicate your novel to, and why?

DL:

To Alex (1976–2007). Alex was a parrot—an African Grey parrot who learned a great deal of human language, and demonstrated an extraordinary range of thought processes. He could also be ornery, and he was entirely loveable. Irene Pepperberg, a scientist who worked with Alex, wrote a wonderful book about the experience, Alex and Me.

Why dedicate a book to a parrot? I’d already dedicated books to my partner, Maureen, and to my children, Naomi and Dominic. It seemed obviously appropriate to dedicate a book such as this one to a non-human person, and I thought someone such as Alex would be particularly appropriate. It’s all too common, I would say, for humans to think of any question marks about dividing lines between the human and the non-human to be a matter of comparing humans with other great apes. But there is so much evidence now of all sorts of non-human animals having an extraordinary range of cognitive skills, of communication abilities—and of feelings. Dogs and cats, of course, but also elephants and pigs and chickens and crows and fish and—the list is a very long one. I’ve become entirely persuaded, incidentally, that the world would be a better place—and that we as humans would be better off—if we stopped eating other animals. But I also think—I hope, at any rate—that it’s very possible to read and enjoy and think about Lucy and Bonbon without being vegan—or even vegetarian or flexitarian, for that matter.

__________________________________________________________

Don LePan has spent most of his adult life working as a book publisher; he is the founder and CEO of the academic publishing house Broadview Press. He has also worked as a taxi driver, a hospital cleaner, and a secondary school teacher. He holds a BA from Carleton University, an MA from Sussex University, and was awarded an honorary doctorate by Trent University in 2004 for his contributions to academic publishing. Lucy and Bonbon is his third work of fiction. His first, Animals: A Novel (2009), received high praise; Nobel Prize winner J.M. Coetzee described it as “a powerful piece of writing, and a disturbing call to conscience,” and Canadian Literature gave readers this advice: “If you read nothing else from this year's batch of novels, read Animals.” LePan’s nonfiction books include a study of Shakespeare’s plots and of cognitive history, an overview of common errors in English, a glossary of literary terms, and a book on the ethics of English usage. LePan is also a painter (a solo exhibition of his work was held in Brooklyn in 2008), and has long been active politically, first within the NDP and more recently in the Green Party of Canada. Born in Washington, DC and raised in Ontario, he spent many years as a resident of Calgary, and has lived for briefer periods in New Orleans, Louisiana; Lewes, Sussex; and Murewa, Zimbabwe. Since 2009 his home has been Nanaimo, British Columbia.