Emily A. Weedon's New Novel is a Tantalizing, Bloodthirsty Thriller

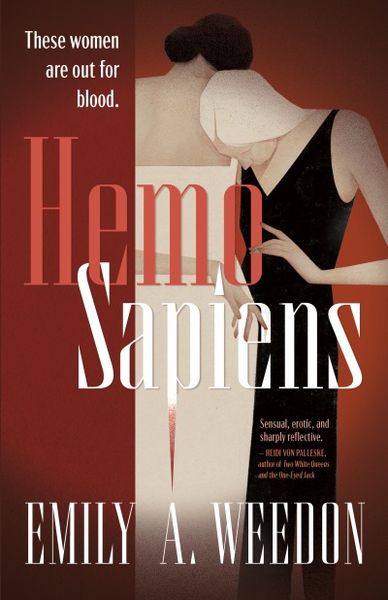

In award-winning author Emily A. Weedon's thrilling new novel, readers are pulled into a sleek and unsettling world where desire, danger, and the supernatural intersect. Detective Luke Stockton is preparing for fatherhood with his wife, Beatrice, when her behaviour begins to shift in mysterious ways. Drawn to a luxurious medspa offering peculiar prenatal treatments and “vampire facials,” Beatrice becomes increasingly distant, while Luke finds himself dangerously captivated by the spa’s enigmatic owner, Cleo, who harbours a deadly secret.

As a series of gruesome murders involving drained bodies rocks the city, Luke’s investigation spirals into obsession. The lines between his work and his private life blur as he hunts a killer who seems to inhabit the same world of secrecy and seduction that has entangled his wife. Every clue draws him deeper into a web of power, eroticism, and deception, where even love becomes a dire risk.

Bold, provocative, and darkly cinematic, Hemo Sapiens (Dundurn Press) reimagines the vampire myth for the modern age. It is a psychological thriller about the hunger for beauty, the cost of knowledge, and the perilous intimacy between predator and prey. This is a story where the body becomes a battlefield and a vessel for deliverance, and where the truth is written in blood.

Check out our Open Book Storytellers Fiction interview with the author below!

Open Book:

How have you bent or broken the rules of these established literary lineages to develop your own style and voice?

Emily A. Weedon:

My first book was dubbed literary. My second has been categorized as some kind of hybrid between literary thriller-horror and mystery. It has sci-fi elements as well because of the anthropology research that went into it. Ultimately, I write what interests me and I reject the idea of any one genre per se. I write in a way I hope interests others. I write as story demands and follow where those demands take me. Genre can be useful in some ways, but in our niche, commodity-driven times I fear it is chiefly useful in the marketing of a product. The writer’s job is to transcend the ugly and sadly necessary activity of marketing and the minimizing cage that genre can be, and speak directly to a reader.

OB:

What impact would you like your novel or short story collection to leave?

EW:

A novel is something that gestates within and is borne out of a writer, sometimes with blood. For a little while after being born, it still belongs to the writer. If it’s taken up by a publisher or agent, it starts to experience rigors. It will be made to stand differently, cut its hair, become less wild, more appropriate.

It’s as if the child the writer bore alone on an island—sharing a language—is taken, adopted, given new ways and rules. Even new names. It could come back years later, in a different skin, having traveled a little. It meets people the writer will never meet. It will have been critiqued, perhaps mocked. If it’s very unlucky, it will be forgotten—or perhaps worse, awarded.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

It will be bought, sold, lent, disagreed over, unfinished, shoveled out of a library along with all the other twenty-year-old books, maybe even burnt. It may come back to the writer, and they could regard one another. The writer will think they remember when the book was novel, and the book may remember the games they played, just the two of them.

Like any writer, I hope my book meets people who are not unkind. Who give it a chance to be itself. Who look past its faults, perhaps even love them. Who don’t ask it to do more than a story should. And who perhaps share it, letting it live, a little. Invite it home, to stay.

OB:

Where do you see your fiction fitting into any specific traditions in Canadian storytelling?

EW:

Let’s pay homage to Cronenberg. To films like Ginger Snaps, The Changeling, and Pontypool. To writers Mona Awad, Nick Cutter, Sydney Hegele, Paola Ferrante, Andrew F. Sullivan, Andrew Pyper, and Kelley Armstrong. Canada does really well at being weird, creepy, other, and strange.

Quoting Katherine Monk in her 2001 book on Canadian cinema Weird Sex and Snowshoes: “Death is an intrinsic part of the Canadian landscape and as much a part of our national psyche as weird sex and snow imagery.”

I believe that exploring horror through literature and film is a kind of gymnasium for our amygdala and our spirit. We live in horrifying times. We test our mettle with the roller-coaster loops of terror to gauge our innate hope, morality, and fitness to survive the shocks that existence throws at us.

OB:

Do you see your work or work like it helping to forge a new path in CanLit, or the broader literary landscape?

EW:

Literary horror and horror in general is having a moment. I believe that artists are pushing horror to the heights of its form and finding that the messages, images, and stories they are telling have deeper resonance than what is thought of by others as “mere” genre.

The image of Oedipus gouging out his own eyes is indeed horrific, as is Medea murdering her children—and these images would be quite at home in modern literature and cinema. I think the world, as it becomes more unstable, recognizes that horror in its myriad forms may most closely mirror the human experience.

I think it may also be experiencing an upswell because, as we become more digital creatures—more plugged in and sensorially and atavistically deprived—we long for catharsis, for extremes. We desperately long to feel. As children, we fear things like swimming out to a far dock that’s beyond our tested ability. Once we can easily swim there, we lose those butterflies at the attempt. We chase the dragon of that first anxiety, knowing that fear and growth are nearby.

What scares us in this world where lattes come delivered to our door? Furthermore, in a post-superstitious, post-religious, and increasingly amoral world, what rules do we need to fear? What boundaries dare we not cross? Horror reminds us we are mortal, that morals exist, that boundaries surely exist—and that there is, in fact, good and evil.

OB:

What is the next story you’re working on, whatever form it may take?

EW:

I have a follow-up to Hemo Sapiens planned, if the gods of CanLit smile upon it. I’m also embarking on editing a short story collection called Whatever, which brings together 20 Generation X voices in fiction to plumb and parse the world we, in many ways, found ourselves in. Did we wash up there? Have we yet got something to say?

I’m also in the very early stages of working on a novel that delves into sibling rivalry, parental favouritism, fame-lust, and emotional incest. The only question is—can I survive promotional efforts and economic realities long enough to get words on paper?

______________________________________________

Emily A. Weedon is the CSA award–winning screenwriter of Chateau Laurier and Red Ketchup, and the author of the epic dystopia Autokrator. She played Lucy in two separate productions of Dracula, and growing up probably checked out Dracula and other vampire books more than anyone else in the Coe Hill library, so it was inevitable that she would write a novel about vampires. Hemo Sapiens is her second novel. She lives in Toronto.