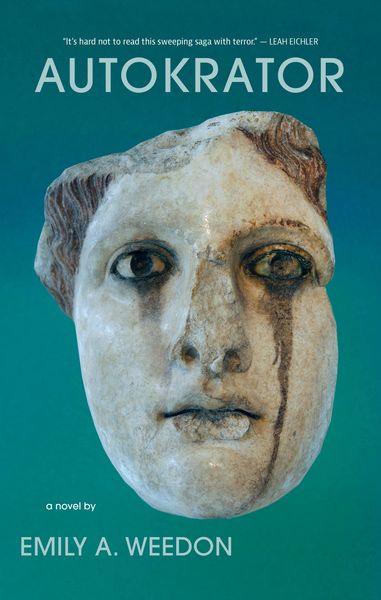

Emily Weedon Writes a Modern Epic in the Debut Novel, Autokrator

Classics and epics are in focus in Emily Weedon's debut novel. Inspired by a broad range of sweeping tales like Ghormenghast, Dune, and even Game of Thrones, as well as the underpinnings of Shakespeare and Greek Mythology, the author has framed an original epic story that posits important and pressing questions about the dire rise of autocracy and the ongoing chaos caused by The Patiarchy.

Instead of opting to stay silent in the face of these broad global troubles, along with personal turmoil and upheaval, Weedon wrote her exciting debut novel, Autokrator (Cormorant Books). The book tells the story of Tiresius, who has risen through the ranks of the Autokracy to become Imperial Treasurer, in turn winning over the trust of the infamous Autokrator. But, she has also broken the rules of this society by posing as a male for years; a gender crime of the more severe order.

As Tiresius continues her rebellion, her path intertwines with that of a Domestic (female labourer) named Cera. She is the true mother of the successor to the Autokracy, who she seeks out so that she might share the truth about his identity, even at the risk of her life.

Read more about this inventive and exhilarating debut in this Long Story Novelist Interview with Emily Weedon!

Open Book:

Do you remember how your first started this novel or the very first bit of writing you did for it?

Emily Weedon:

When I sat down to write Autokrator, my debut speculative novel, I was a trailing spouse in a failing relationship alone in a foreign country. My mind was atrophying while I toiled as the sole caregiver to a toddler. I wondered, pent up in my glass cube above Liszt Ferenc Tér, how many women before me had suffered in that position, how many had been forced to put their ideas and ideals second and their domestic burden first. How many ideas has the world lost out on because the bright women who had them were hobbled by competing burdens of lack of access to education, to health care, to TIME as individuals?

This was not the world I was promised as a young girl in the 1970s. As a writer, as a creative, I found myself wondering, “How much Worse could the Patriarchy be?” My novel, became one answer to that question.

OB:

How did you choose the setting of your novel? What connection, if any, did you have to the setting when you began writing?

EW:

I lived in Europe for almost a year, when I started writing Autokrator. I was surrounded by history and architecture on an eye-opening scale. I found myself diving into history I could read to understand the history I was seeing. I’ve always been drawn to ruins and especially moved, creatively, by exploring places, wondering who lived before me, and how. The Budapest Opera house, for example. Sitting in a box seat watching La Boheme, I found myself wondering which historical characters sat in this very seat, leaned on this balustrade?

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

I needed the world of Autokrator to be speculative, unleashed from the confines that telling a story in this world imposes. I didn’t want to be dealing with a world shaped by Judeo-Christianity, for example, which brings so much baggage to the way we view genders. I wanted a tabula rasa so I could populate my story with women and men from outside our familiar contexts. I think this is the same reason Orwell chose to set Animal Farm amongst animals — to be able to focus on theoreticals, and to put the message of his work in sharper relief.

In addition to wanting to create a sort of lab where I could play with my ideas, I wanted my world to be drawn on a big canvas. I loved books like Ghormenghast, Cloud Atlas, Dune, The Tale of Genji and even A Game of Thrones. I grew up on CS Lewis, Tolkien, fairy tales, and Greek mythology. I wanted to build an exciting world with the swash and buckle of Shakespeare, something sweeping and grand. I was inspired by places I’ve been able to visit like Schönbrunn Palace in Austria, the 3rd Century Roman ruins of Palmyra in Syria, the gilded bathhouses in Budapest, and the earthy tunnels under Casa Loma in Toronto. It was Schönbrunn where the idea of women living behind the walls and below the floors crystallized for me — because they have secret passages used by servants so work could happen invisibly. As much as Autokrator is a book about ideas, I always wanted it to be a propulsive, plot-driven story, and a ripping read. The grandeur of the setting was also pure pleasure to imagine and create.

OB:

Did you find yourself having a "favourite" amongst your characters? If so, who was it and why?

EW:

Without a doubt, Tiresius is my favourite fiction child. Her struggle to make something of herself, swimming against the currents of a world that despises her makeup. Her salty, unabashed hunger for power and ambition makes me adore her. I love that she treasures her brain, surrounded as she is by weaker minds and despite the accident of her birth. She is haughty and vain and held up by her own puffery at times — a bit of an Iago, a bit of a Machiavelli. I always pictured Tilda Swinton’s Orlando when I saw her. I was also inspired by Anne Marie MacDonald’s Goodnight Desdemona, Good Morning, Juliet. It was MacDonald who showed me in my early 20s that it was possible to create female characters that were active, adventurous, exciting and not just mothers or objects of desire.

OB:

What was the strangest or most memorable moment or experience during the writing process for you?

EW:

I had no idea what I’d wrought when I first began this. I was a screenwriter first, and had no pretensions of writing novels. I packaged up what I had, some 100 pages and an outline and sent it to Adrienne Kerr who was working as a substantive editor at the time. I feared Adrienne would tell me I’d created some kind of abomination and ask me to show myself out! Instead, she was the book’s earliest champion and her editorial was like the support of a sister in arms. She was the first person to say she believed the book could go somewhere. Her kind words kept me company during the many rejections that followed, and still do.

OB:

Did you celebrate finishing your final draft or any other milestones during the writing process? If so, how?

EW:

I make a point to celebrate all the stages of writing. First drafts, signings, first literary agents, printings, final line, copy and proof edits, launches, and sometimes even just a good day’s page output by eating well and having a glass of something sparkly. Life is too short to do otherwise.

OB:

Who did you dedicate your novel to, and why?

EW:

I dedicated Autokrator to my mother who tried very hard to beat terminal cancer long enough to see the publication of the book. She got her diagnosis before I was signed, and sadly lost her battle only 4 months before publication. Tiresius would have approved of my mother’s piss and vinegar. The final proofs were coming in during my mothers final hours. The next one will be dedicated to my daughter, Ginger, who is long-suffering of a single mother who is also a writer.

OB:

Did you include an epigraph in your book? If so, how did you choose it and how does it relate to the narrative?

EW:

Hannah Arendt is one of the finest minds ever to write on Totalitarianism, Power, Violence and Political Theory. I chose her quote: “…those who hold power and feel it slipping from their hands… have always found it difficult to resist the temptation to substitute violence for it...” because it echoed the arc of Donald Trump so clearly. His attempt to substitute autocracy for democracy is not the focus of Autokrator but without question, his naked thirst to subvert norms of politics and government created the climate I lived in while writing this book. I was thinking about The French Revolution, and the Russian revolution, and Queen Xenobia’s revolt against Rome as well, and so many other flashpoints in history when empires and regimes fall. Those are messy times when the winners rewrite histories which will go on to be rewritten again. The inherent warning in the book is Lord Acton’s adage “Power corrupts, absolute power corrupts absolutely.” No matter how just the heroine, Power is channeled but rarely wielded for long.

____________________________________________________

Emily A. Weedon is a debut author and an award-winning screenwriter. She co-created the series Chateau Laurier, the most awarded web series in the world in 2023. She and co-writer Kent Staines were awarded Best Writing in a Web Series at the Canadian Screen Awards in 2023. Emily has been a graphic designer, musician, set painter, and art director. She played music professionally and has released 3 EPs. She lives in Toronto, Ontario with her daughter, Ginger.