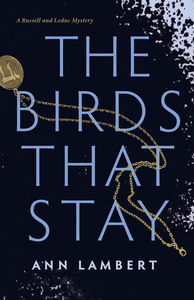

Excerpt! Get Hooked on the Mystery in Ann Lambert's Dark Quebec Tale, The Birds That Stay

In the opening of Ann Lambert's The Birds that Stay (Second Story Press), Louis Lachance sneaks away while his wife is sleeping - not for an affair, but to take one more job as a handyman. Instead of helping Madame Newman out around the house though, he finds something deeply shocking - an act of violence that sweeps his whole Laurentian village into a gruesome intrigue.

Roméo Leduc, the Chief Inspector, and Marie Russell, the victim's neighbour, find themselves thrown together in an investigation that stretches into the wilds of Quebec, 1970s Montreal, and even WWII Hungary.

The Birds That Stay has been called "masterful", "skillful," and "engaging", and we are thrilled to present an excerpt for you here today, courtesy of Second Story Press. Kick off your weekend with a great read - and if you need more, pick up a copy of The Birds That Stay and read on!

Excerpt from The Birds that Stay by Ann Lambert:

When will redemption come?

When we grant everyone

What we claim for ourselves.

SHE WAS JUST SETTLING into her evening tea, a minty concoction she made herself from that wildly invasive plant that threatened everything trying to survive around it. She sank into her ancient armchair and realized she’d forgotten her crossword puzzle from that morning in the kitchen. She heard a noise outside. Then she heard it again. Must be that pesky porcupine that liked to chew on the side of her house. She wasn’t unsympathetic to it. All rodents had to constantly keep chewing as their incisors never stopped growing. Porcupines, too. She just wondered what it was about her cabin that appealed to this one so much. The wood stain? Salt in the wood stain? Because it was there? The upside to this was she was offered a close-up view of a distracted animal—one she could photo- graph and then recreate in charcoal at her leisure afterwards. She peered out into the blue light of dusk—it came earlier and earlier now, and she had to brace herself for the low-grade depression that stalked her from November to March, when the light returned. Nothing there. But still she called for Kutya to join her—just the presence of a dog, even a toothless, timorous one, could often persuade a wild animal to abandon its mission. She lifted her plaid jacket from its hook and slipped into her old leather boots by the back door. It was probably five below zero out there tonight and the chill no longer seeped into her bones—it invaded them with sticks and knives. She stepped outside and took in the cold air. It was as though the season was changing at that very moment. The stars were just coming out, a crescent moon dangled low in the southeastern horizon. How many more nights would there be like this? She shone her flashlight along the edge of the house where it met a few tufts of rogue weeds, now brittle underfoot. There was nothing there. She turned to another sound behind her. And then she understood.

One

LOUIS LACHANCE EASED into the driver’s seat of his ancient Toyota pickup and turned the key, grateful that he’d had the muffler replaced a week earlier. He had a little job to see to that morning, but he had to escape his house, undetected, first. The engine sputtered to life, and the tires crunched along the gravel driveway as slowly as a hearse. He felt quite safe that Michelle was still asleep, her mouth slightly open, snoring like a man. If he was lucky, he could be done and back home before she woke up.

Louis Lachance was a retired homme à tout faire. Except retirement had been Michelle’s idea, not his. He still loved driving the dirt roads he knew like old friends and working for the few customers who really counted on him, year in, year out. He closed down houses for the winter and opened them up again in the spring for les anglais from the city. He fixed pipes burst by early freezes, replaced locks with lost keys, fixed jammed windows. He was not a crook like those guys from town—charging people hundreds of dollars for a few hours’ work. He was an honest man. A trustworthy man. And at eighty-six years old, an old man.

He was especially fond of Madame Newman. Even after all these years, she never insisted he call her by her first name like so many did now. She always had a good cup of coffee ready for him when he was done, and a homemade muffin— banana-chocolate, his favorite, another thing forbidden to him by Michelle. Madame Newman was old—almost as old as he was—but she had the most startling blue, round eyes, and golden-gray hair that she knotted into a perfect chignon as though she’d woken up that way. She was always in her garden, which was one of the most efficient and intelligent ones he had seen. She grew enough food in that little plot of land to see her easily through her year, and then some. She always paid him in cash and didn’t follow him around pretending to understand what he was doing. They never talked much—it was clear Madame preferred the company of her dog and garden to that of humans—but Louis Lachance understood that well. Very well, indeed. Everyone today talked too much. Talked too much about too little. Ça parle trop pour rien. He sometimes imagined himself arriving at Madame’s house in the late afternoon, with a bottle of wine, and the two of them watching the sun disappear behind the hill from her back porch, while listening to the afternoon birds singing their diminishing song to the trees.

He turned down the unmarked road to her house, passing an overturned garbage can. The bears had obviously gotten to it, the last big feast before hibernation. He would clean that up for her on his way out, if he had time. His window of opportunity with Michelle would open only so far. He turned into Madame’s driveway and was surprised not to be greeted by her dog, Kutya, barking from nose to tail so ferociously his whole body spasmed with the effort.

The sun was almost hot now, unusual for a late October morning. The leaves were well past their prime, but still glorious and radiant against the deep blue of the sky. He hoisted his tool belt from the back of the truck and stepped carefully down her uneven flagstone walkway to the side door to the kitchen. He could not afford a broken hip at his age. She was usually waiting for him, working on a crossword puzzle, sipping coffee. The paper was on the table, a pencil resting on it, next to her coffee cup. The radio was on, a honey-voiced host explaining the piece of music he was about to play. Louis was uncomfortable entering her house without permission, although he knew she wouldn’t really mind. He stepped into the kitchen and called her name. Her little gray Subaru hatchback was parked in its usual place. But where was Kutya? They must have gone for a walk. Louis turned to head out of the kitchen, grabbing a muffin on his way. Then he put it back. He did not want her to think he had no manners. And Michelle would be furious. Well, she was going to be furious anyway when she found out he’d been out on a job, another strictly forbidden activity. (For a few months, Michelle insisted she tag along if he refused to stop working. He made her help him carry a hundred-pound water tank, which she dropped in mid-move, almost killing him, and breaking her toe. But she was a stubborn woman, and now he only took jobs in the early morning when she could be counted on to sleep in.)

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

He glanced out the kitchen window to the garden, but there was no one there. He was tempted to just walk through it—even in late October it was beautiful. The hydrangeas had dried to a delicate pink, the winterberries a brilliant orange. A larch tree glittered gold in the sun. Louis headed back to his truck, feeling more disappointed than he should have. He had to admit that in another life, he and Madame Newman might have been very good friends. Just then, a splash of something bright red interrupted the thought. It was a pile of rags over by the compost bin. And there was the dog, Kutya, lying down next to it, panting in the hot sun. Louis limped closer to investigate. Kutya stretched to his feet, approached Louis, his tail wagging cautiously. It was then that Louis realized the pile of rags was a person, and as he hobbled closer, he saw it was Madame Newman, lying face down in an empty flower bed. He turned her half onto her back and knew immediately that she was dead. Her skin was leathery and cold. Her lips were blue, but not as blue as those open eyes that he was too terrified to close, like they do in the movies. The dog began to whimper very quietly, as though the mourning process could begin now. Louis Lachance, married for sixty-four years to Michelle Dupuis, sat on the dew-damp earth beside Madame Newman and began to cry.

For more of The Birds That Stay by Ann Lambert, visit the Second Story Press website

______________________________________

Ann Lambert has been writing and directing for the stage for thirty-five years. Several of her plays, including The Wall, Parallel Lines, Very Heaven, The Mary Project and Two Short Women have been performed in theatres in Canada, the United States, Europe and Australia. She has been a teacher of English literature at Dawson College for almost twenty-eight years in Montreal, Quebec, where she makes her home.